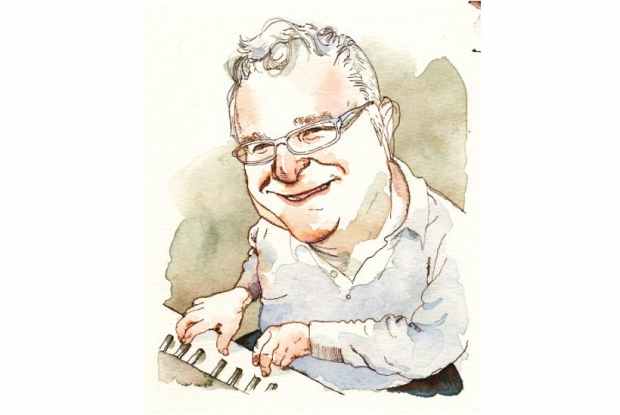

Randy Newman is already struggling to keep up with himself. His dazzling new album, Dark Matter, was written before the changes of the last year, and no matter how pointed and current some of it is, there’s something missing. ‘There was a newspaper article that said Donald Trump is like a character in a Randy Newman song,’ he says.

Already a subscriber? Log in

Subscribe for just $2 a week

Try a month of The Spectator Australia absolutely free and without commitment. Not only that but – if you choose to continue – you’ll pay just $2 a week for your first year.

- Unlimited access to spectator.com.au and app

- The weekly edition on the Spectator Australia app

- Spectator podcasts and newsletters

- Full access to spectator.co.uk

Or

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in