Liverpool is the New York of Europe. The business district looks like old Wall Street: a miniature Lower Manhattan on the Mersey. It’s a city of scale, drama, melodrama, tragedy and comedy. Not to mention rich and poor. And often all these effects are simultaneous.

No other British city has a similarly contrary architectural character: superb, shabby, romantic, melancholy, proud and mean. You cannot be in Liverpool and not be affected by its buildings. I grew up there and long before I knew what ‘design’ meant, Liverpool had taught me to see — as well as to feel the deadly weight of history. It’s an architectural education.

But Liverpool has not treated its architects well. In his early twenties, Harvey Lonsdale Elmes won the competition to design St George’s Hall — civic ambition writ very large with pediments and volutes — but the city fathers, thinking him too sickly and inexperienced, took the job away. Elmes died of neglect and TB in Jamaica in 1847 aged just 33. Nikolaus Pevsner, and many others besides, came to consider Elmes’s St George’s Hall the greatest neoclassical building in Europe. Its designer never saw it finished.

In 1864, a local architect called Peter Ellis built Oriel Chambers on Water Street, a design preternaturally ahead of its time with a metal frame and glass-curtain walling. It predicted the Chicago school of skyscrapers by 20 years, but a savage review in the Builder meant no more work for Ellis, who soon died in obscurity. Eventually, his reputation was made when Pevsner included him in the influential Pioneers of Modern Design.

More recently, Will Alsop was monumentally jerked about with his proposal, hubristic to some, for a ‘Fourth Grace’ to accompany the magnificent Pier Head threesome of the Royal Liver Building, Cunard Building and Port of Liverpool Building. It was this heroic waterfront trio that inspired the Unesco World Heritage citation: Liverpool is the ‘supreme example of a commercial port at the time of Britain’s greatest global influence’.

But Alsop’s bold whimsy was to be no part of it. Other architects working in Liverpool during the City of Culture period became restive and fearful after Alsop’s bruising at the hands of crude local interests, nicely described by the architectural journalist Paul Finch as ‘nihilistic political infantilism’. The amiable Alsop sighed in resignation and said: ‘The Liverpudlians do not deserve such a wonderful place.’

So it’s remarkable that an ambitious new regional architecture centre called Riba North opens this month, on a site near to Alsop’s unrealised dream. But with a contrariness typical of the city, it’s in a building designed by Broadway Malyan, a big commercial practice of no known artistic distinction. At least, not of the positive sort: the Mann Island Buildings, which house Riba North, were shortlisted for the 2012 Carbuncle Cup, a prize for ugly buildings. The first exhibition, evidently without irony, comprises drawings and models of unbuilt Liverpool from Riba’s world-class collections in London.

Liverpool was, of course, deplorably damaged by Hitler’s Terrorflieger, on account, it has been speculated, of an unhappy period a young Adolf spent lodging at 102 Upper Stanhope Street in Toxteth where his half-brother Alois lived with his Irish wife, Bridget. The immediate architectural impulse after 1945 was to make good Hitler’s systematic and vengeful destruction. The architect and councillor Alfred Shennan, in a delirium of Macmillan-era futurism, proposed four-lane inner ring roads and multistoreys for 36,000 cars: the exhibition shows a lovely 1963 skyline by the town planner Graeme Shankland, 2m wide, which followed Shennan’s lead. Not everyone properly sensed the euphoria. Simon Jenkins has compared Shankland to Bomber Harris, a tasteless remark given Merseyside’s unfortunate relationship to high explosives. Gavin Stamp called it a ‘nightmare’, but he is someone who wears a fragment of Pugin altarcloth as a necktie. I can remember the sordid Liverpool slums and wretched bomb sites that made a left-lyrical remedy of modern amenities and services with clean people in cars seem very attractive indeed.

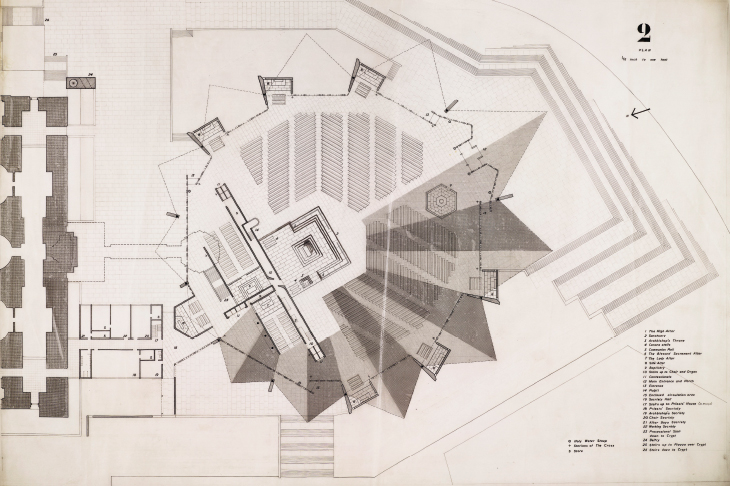

The Shankland vision was never realised, nor was Richard Seifert’s 1966 design for a 42-storey ‘River City’ which, if built, would surely have accelerated Liverpool’s sluggish and hesitant approach to the 21st century. Instead, in bipolar Liverpool of proddies and paddies, the cathedrals were preoccupations of architects. There is a vivacious drawing by Edwin Lutyens for the Catholic cathedral, a baroque phantasm, but only the crypt was built. On top of it today is Frederick Gibberd’s Christ the King, a thin and brittle take on an Oscar Niemeyer original in Brasilia. A more sophisticated design by Denys Lasdun, starburst in plan, was rejected.

The Anglican cathedral is stronger meat. Sir Charles Archibald Nicholson proposed a hexagonal design covered with a dome, but Giles Gilbert Scott won the competition with an awe-inspiring Gothic temple which, this being Liverpool, is still unfinished. Anyway, Liverpool allowed Scott to claim to be the author of one of the country’s biggest buildings, as well as one of its smallest, the famous GPO telephone box. Meanwhile, the sublime canyon around the Anglican cathedral has inspired both suicides and architects: in the exhibition is a hitherto unpublished and thrilling drawing of 1931 by student Stirrat Johnson-Marshall, a design for a vertiginous processional bridge over the horrible Piranesian chasm.

Forget nightmares, there is an oneiric quality to an exhibition of drawings of buildings that do not exist, but that’s appropriate to Liverpool, which has an oneiric quality all its own. C.G. Jung wrote tellingly about the city’s mysterious properties without (it seems likely) ever actually visiting. He called it the ‘pool of life’ and in 1987 a statue in his collective memory was erected in Mathew Street, near the Cavern where the Beatles were incubated. This being Liverpool, it was promptly vandalised. Surrealism is everywhere under those blue suburban skies. ‘A Hard Day’s Night’, as Paul Du Noyer explained, was not clever invention, just the way they speak.

In 1965 Allen Ginsberg said that Liverpool was the ‘centre of human consciousness’, but those were drug-fuelled years. Riba is right, however, to call the city a ‘mover, shaker’: Liverpool had the country’s first university schools of art and architecture, in 1893 and 1895 respectively. Town planning was established here as an academic discipline, with, it must be admitted, mixed local results.

Still, at a moment when the intellectual and moral quality of debate in the country is at a dismaying low, a bold architectural initiative in a provincial city properly famed for its magnificent buildings is a nice reminder that there are more beautiful, enduring and life-enhancing things than politics. After all, buildings last longer. And when they have never been built, they last for ever in the imagination.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in