As we waited for curtain-up on Scottish Opera’s new production of Bartok’s Bluebeard’s Castle a member of staff walked out on stage. Don’t worry, he reassured us, he wasn’t about to announce that a member of the cast was indisposed. Nervous laughter from the auditorium. Still in the same matter-of-fact tone, he carried on, and I’ll admit that only at this point did I twig that this wasn’t a member of staff and that he was actually delivering a cleverly skewed version of the librettist Bela Balazs’s spoken prologue to the opera — something more often omitted than performed. Here, in a translation by Simon Rees, its bluntness coupled to that simple, unsettling theatrical trick worked superbly, establishing an atmosphere of vague unease that carried over into the opening scene.

Which was just as well, because the setting of Matthew Lenton’s production is a suburban living room, with a cheap sofa and a laptop open on a desk. Bluebeard (Robert Hayward) and Judith (Karen Cargill) stumble blearily on in dressing gowns and pyjamas, and by the time the first of the castle’s seven doors turns out to be that laptop, it’s all looking depressingly like a Bluebeard for the Gogglebox generation. Then, with the opening of the second door, jagged shards start to protrude from the soft furnishings. With the fourth door, predatory tendrils of foliage sprout from drawers and behind cushions; and a disgusted Judith finds blood on her hands. As the fifth door opens and trumpets appear in the stage-side boxes for Bartok’s shattering central climax, designer Kai Fischer’s set finally flies apart, leaving the characters in a surreal mindscape as uncanny and as potent as an image by Magritte.

It’s powerfully done. Lenton gauges precisely how far that initial gambit will carry him — and how far, too, he can lean on Hayward and Cargill’s tremendous individual performances. If the sheer nobility of Hayward’s majestic, black bass-baritone at first seems at odds with his dishevelled appearance, the detail and subtlety of his partnership with Cargill is compelling from the off. Cargill’s Judith is no innocent newlywed, and her singing reflects it: coolly draining the colour from her voice as she reacts to the revelations behind each door, then hurling blazing shafts of tone at Bluebeard as her demands grow ever more stringent. He, in response, shakes with anxiety rather than rage, all the while singing with an eloquence that makes you wish we heard more operas sung in Hungarian.

Together they offer a painfully realistic portrayal of a lived-in relationship; a couple that instinctively turn to each other for little shoulder-squeezes of comfort even as, with brutal intimacy, they twist the emotional knife. Sian Edwards, conducting, drew some of the best playing I’ve heard from the Scottish Opera orchestra, generating the inexorable momentum of a passacaglia. The great meshing and locking of orchestral gears as Judith makes her final, fatal demand was as terrifying as anything on stage.

Before the interval came the world premiere of The 8th Door, a sort of commentary on Bluebeard by Lenton and the composer Lliam Paterson. According to Lenton, we were witnessing the birth of ‘a brand-new medium’, drawing on the resources of his theatre company Vanishing Point. What we saw was those two familiar stock characters from contemporary opera, Anonymous Woman and Anonymous Man, seated on stage before a huge screen on which, with the aid of video cameras and a collection of props, their faces silently acted out the melancholy course of a relationship. In the pit, Paterson’s enjoyably Berg-ish score splashed and surged, with singers weaving in fragments of text by Hungarian poets. Impressively performed and lit, the effect was of an art installation based on one of those cultural theory essays beloved of opera programme-book editors. It’s hard to imagine it making much sense away from Bluebeard, in the unlikely event of a revival.

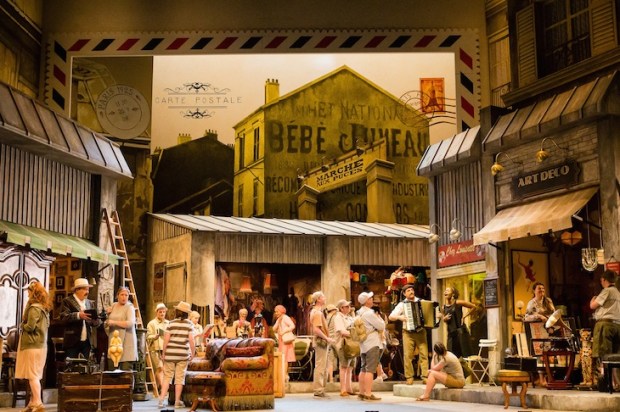

La bohème is a more bankable proposition, and Annabel Arden’s 2012 staging for Welsh National Opera is already on (at least) its third outing. But you’ve got to keep revivals in good repair. At the Bristol Hippodrome, the crisp line-drawings of Paris cityscapes that, carefully lit, help give this production its luminous, frosty magic often vanished into a drab grey wash. The images projected on the front-cloth were blurred. A pity, because everything else glowed, with a particularly ardent and impulsive central pairing of Dominick Chenes as Rodolfo and Marina Costa-Jackson as Mimi, and conductor Manlio Benzi making Puccini’s score alternately dance like a scherzo and brim over with warmth. In this theatre the orchestra is practically on the same level as the audience, yet Benzi kept things so transparent and graceful that the singers were never at any risk of being overwhelmed. You could see the players smiling too.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in