Rudolfo Paolozzi was a great maker. In the summer, he worked almost without stopping in the family’s ice-cream shop, making gallon after gallon of vanilla custard. In the slack winter months, when the shop made its money on cigarettes and sweets, he built radios from odds and sods. It was on one of these homemade radios that he heard Mussolini’s declaration, on 10 June 1940, that Italy, the country he had left for Scotland 20 years before, had entered the war. That night a mob attacked the ice-cream shop at 10 Albert Street, off Leith Walk in Edinburgh. The family lived above the shop and later, Rudolfo’s son Eduardo, then aged 16, would remember how it had been before and what the men had done.

‘The carefully arranged shop windows usually had been “dressed” by a visiting confectionary representative — with sundae dishes holding ice creams fixed in perpetuity on some composition material and chocolates made of composition materials in glass bowls filled with crêpe paper. In the shop itself on glass shelves backed by mirrors were glass jars containing the real things. In very little time this world which had existed for a decade and a half was reduced to splintered wood and small pieces of broken glass.’

Eduardo Paolozzi was on the side of the makers: the confectionary man who styled the windows with crêpe and cardboard, his father who had built radios and helped him with model airplanes. Together they had built Meccano and a Trix Twin Railway engine with a battery motor.

Aged 20, studying at the Ruskin School of Art in Oxford during the war, he sketched heads after Dürer and Rembrandt in the Ashmolean Museum and African sculpture at the Pitt Rivers, but realised that what he wanted, all he wanted, was to ‘make things’. The Ruskin didn’t offer sculpture so he transferred to the Slade in London. Living in digs at Cartwright Gardens, eating rationed bacon and pasta shells sent by his mother, he began making with a fierce concentration.

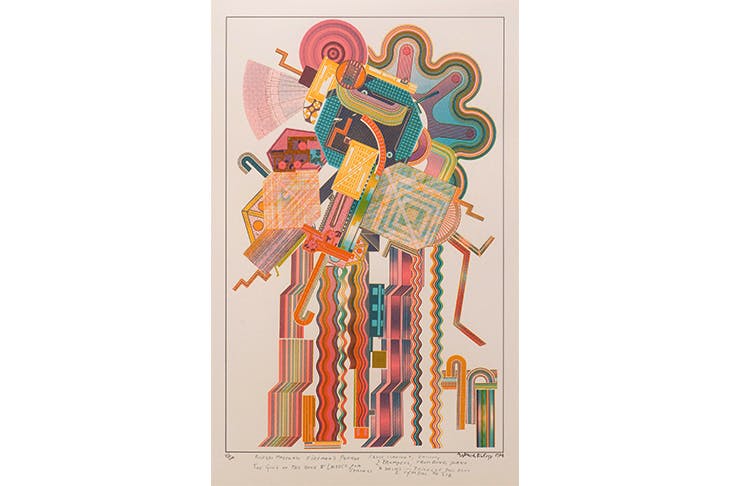

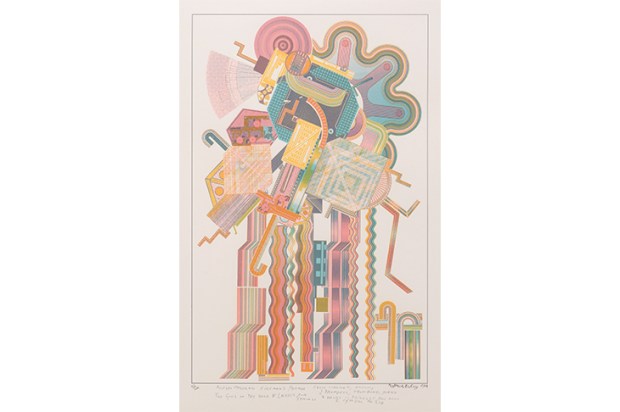

A pair of photo-lithographs of ‘The Sculptor’s Studio’ (1977) hang in the last room of the Whitechapel Gallery’s Eduardo Paolozzi retrospective. They show a workspace crammed, skirting to rafters, with models, tools, materials, scraps and rubbish. Cluttered, but with a sense that its owner could find you anything you wanted, from a plastic frog to a bronze head of Wittgenstein.

Everything interested him. Asked on Desert Island Discs in 1990 about his mania for collecting ‘junk’, he replied defensively: ‘I’m very selective about the kind of junk.’ He collected cigarette cards, clock parts, broken combs, bent forks, bits of bark, kitchenware from Woolworths and magazines given to him in Paris by the wives of American GIs. He talked of the cuttings he pasted in his scrapbooks as being ‘like exotic and rare butterflies mounted in the Natural History Museum’.

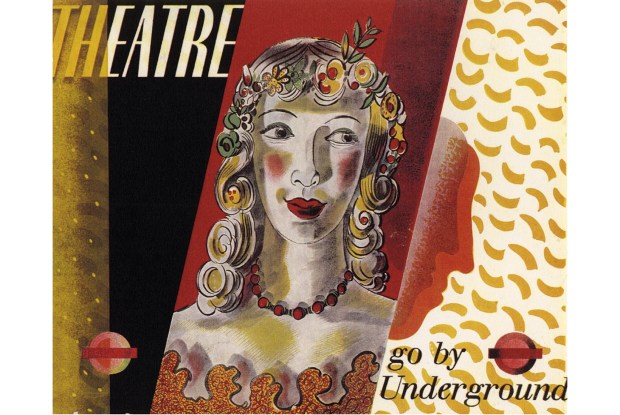

You have a sense of this in the Whitechapel’s early rooms, as Paolozzi flits from idea to idea — Picasso, abstraction, the figure — and medium to medium — concrete, plaster, screenprint, film. He tries his hand at a printed fabric for a cocktail dress sold by Horrockses Fashions (1953), and later a djellaba tunic for Lanvin (1971) and bone-china plates for Wedgwood (1968/9).

Paolozzi was not a slim man — blame the ice cream and pasta shells — but you do have to run to keep up with him. While you’re admiring the homely wool of the ‘Whitworth Tapestry’ (1967), he’s on to sheeny-shiny chrome-and-aluminium ‘Silver Sixties’ sculptures. He rejected the label ‘pop artist’. Donald Duck and Goofy may grin from his screenprints and Mickey and Minnie Mouse share an Eskimo-kiss nose-to-nose in the ‘Whitworth Tapestry’, but Paolozzi was clear: ‘If I am called a “pop artist” then people expect to see soup tins.’

You see him in the Whitechapel exhibition having a joke about such labels. In his screenprint ‘Avant garde’ (1971) each letter of the phrase is filled with a monster pulling a googly face. He invented his own word, ‘Bash’, which stood for ‘Baroque All Style High’. It didn’t catch on.

Paolozzi was garrulous, a prolific writer of letters of complaint, untitled poems, unfinished novels, explanations and exculpations of his work. The curators Daniel F. Herrmann and Cameron Foote have been reticent. I’m usually for minimal gallery texts, but in the case of Paolozzi, as he ‘shuffles’ — his word — between one scheme and the next, you want guidance. As he dashes ahead, you need someone to help you play catch-up. The catalogue, if you can stretch to £30, is superb.

But making is nothing, said Paolozzi, without looking. When he taught ceramics at the Royal College of Art in the 1980s, he wrote this report: ‘Finding the courage to be truly creative, finding the courage to be truly disciplined, realising that endless hours of just “making” leads inevitably to some form of mediocrity, finding the discipline to go to the Tate and enjoy Blake or stare at cubism, learning that an hour at the National Gallery can be more influential than a trip to the Crafts Council — that is what we must instil.’

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in