What a strange affair it now seems, the Mansion House Square brouhaha. How very revealing of the battle for the soul of architecture that reached maximum ferocity in the late 1980s and which still echoes today. Where developers now jostle to build ever taller, fatter and odder-shaped City skyscrapers, this was a time when it took 34 years to get just one building built. An ambitious bronze tower and plaza by the German-American modernist pioneer Mies van der Rohe was finally rejected in favour of an utterly different post-modern corner block (with no plaza, but a roof garden) by Sir James Stirling. Both were shepherded by a man in search of his personal monument: the property developer Peter, now Lord, Palumbo.

The story is retold in a new exhibition and cluster of talks and debates at the Riba gallery which examines the work of both architects and the improbable history of the affair. The saga began in 1962 when the 27-year-old Palumbo, then working with his hugely successful bombsite-developer father Rudolph, first asked the ageing Mies to design them a building for a site to be carved out of existing good Victorian buildings facing the side of the Mansion House. It finally ended in 1996 when the replacement Stirling building, Number One Poultry, opened. Both architects had died in the meantime, Mies at 83 in 1969 and Stirling — unexpectedly, as the result of a botched operation — in 1992, aged only 66. It must have seemed that theproject was cursed, and not just by conservationists.

Hugh Pearman and John Rentoul debate the merits of modernist (and post-modern) architecture:

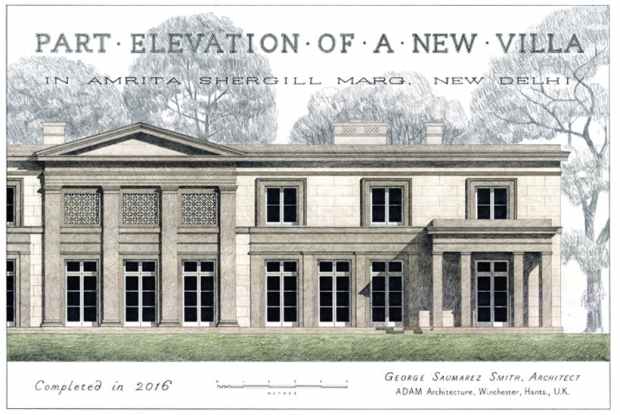

Dapper, precise Miesian modernism was quite the corporate thing in the early 1960s but had gone out of fashion. Palumbo commissioned the design in the full knowledge that it would take years for him to assemble all the plots of land needed to build it. Fatal error: just as he was finally ready, in 1984, Prince Charles (with whom Palumbo was a polo-playing chum) launched his new role as a traditionalist scourge of modern architecture with a full-frontal attack on it. ‘It would be a tragedy,’ he said at a dinner meant to be celebrating architecture, ‘if the character and skyline of our capital city were to be further ruined and St Paul’s dwarfed by yet another giant glass stump, better suited to downtown Chicago than the City of London.’ This was dynamite: the public inquiry into the scheme was in progress. Charles effectively killed Mies’s Mansion House Square. That meant not only no tower, but also no square: this would have been the only large civic space in the City. But then Wren had also failed to do the same thing on the same spot following the Great Fire of London.

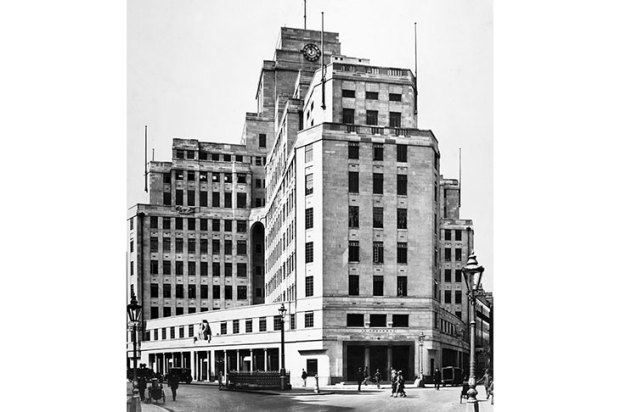

Palumbo swiftly regrouped and signed up ‘Big Jim’ Stirling, who was a very different, gamier kind of architect from Mies. The post-modern (po-mo) building that resulted, which was neither a tower nor a square, was delayed by further conservationist protests and a second public inquiry. Charles didn’t like Stirling’s offering either — ‘a 1930s wireless set’, he sniffed in 1988. But by then his one-liners were losing their force. Stirling won, but the delays meant that by the time ‘Number One Poultry’— named after one of the streets it faced — opened it was not only posthumous and monumental, but monumentally unfashionable.

And today? Architecture is in a pluralist phase. There is no commanding ideology or style. Po-mo has swung back into fashion — No. 1 Poultry is now itself a listed building, at a higher grade than the Victorian group it replaced. We can also see the merits of Mies’s Mansion House Square scheme, complete with very high-quality models seen for the first time in decades. It is a thing of wonder as much for the square as for the tower. Whether or not it would have turned out well — the square itself was an uneasy compromise with existing roads — it has attained lost-masterpiece status.

The exhibition looks into these very different architects’ way of working. Mies was the ultimate auteur while Stirling, famously arrogant, bloody-minded and charming, solicited all manner of design ideas from others in his office, which you see bound into ledgers in this show. There’s also a model of No. 1 Poultry that Stirling’s assistants mischievously had made into a wireless set. And there’s his 1988 letter offering to return his Royal Gold Medal for Architecture (awarded by the Queen in 1980) on the grounds of her heir’s hostility. Palumbo talked him out of sending it, but Stirling insisted it be archived. His knighthood was announced just 12 days before he died. Palumbo, made chairman of the Arts Council and a baron by Margaret Thatcher, finally sent in the bulldozers in 1994.

Weird times, eh? All for a patch of land in the City that had been built and rebuilt endlessly since Roman times but which had hit a moment of aesthetic indecision and inertia. At the time nobody knew what architecture was going to become, stylistically. For different, rather more pleasurable reasons (anything goes) we still don’t.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in