How to celebrate the centenary of the Russian revolutions of 1917? Modern Russians are deeply divided over the legacy of that tumultuous year. Russia’s few remaining liberals remember that the overthrow of the tsar in February 1917 ushered in a flowering of the artistic avant-garde, a brief period of feminism, liberal values and democracy. Putin supporters, on the other hand, have been convinced by years of state television propaganda that popular revolutions are by definition dangerous and anarchic, and usually orchestrated by dark outside forces. Whether in Maidan Square in Kiev in 2013, Tahrir Square in Cairo in 2011 or Palace Square in Petrograd in 1917, the very idea of the people taking power into their hands is anathema to the Kremlin’s ideologues.

So the anniversary of the coup that brought the Bolsheviks to power and led to the creation of the USSR presents a dilemma for Vladimir Putin. He reveres the Soviet Union, which he served as a Communist party member and KGB officer, but abhors the popular uprising that created it. In recent years the Kremlin has invoked various chunks of Russian history to boost Putin’s legitimacy, erecting statues to Prince Vladimir of Kiev and Ivan the Terrible and rewriting history books to cast Stalin as a heroic war leader rather than a genocidal murderer. There’s no modern party line on the revolution, however — no ‘official’ or ‘patriotic’ version. The conservative prerevolutionary prime minister Pyotr Stolypin — famous for hanging revolutionaries from ‘Stolypin neckties’ — is probably the closest thing to an official hero of the period. Stolypin was elected ‘history’s greatest Russian’ in a TV phone-in in 2008 (a rigged poll, it turned out — Stalin got more votes).

Like Stolypin, Putin is first and foremost a Russian imperialist, and a believer in stamping out dissent. Putin has made it clear that he regards the Bolsheviks who toppled the state as dangerous traitors. Lenin and his professional revolutionaries ‘betrayed Russia’s national interests’, he told young activists at the annual Kremlin-run Seliger national youth forum in 2015. The Bolsheviks ‘wished to see their fatherland defeated while heroic Russian soldiers and officers shed blood on the fronts of the first world war’. The revolution, in Putin’s view, caused ‘Russia as a state to collapse and declare itself defeated’.

When the official Revolution Day rolls round on 7 November, the Kremlin will doubtless celebrate with a grand military parade in Red Square. But if last year’s was anything to go by, it won’t be a celebration of the original ‘colour revolution’. The Kremlin will be commemorating a different anniversary — the famous parade overseen by Stalin on the revolution’s 24th anniversary, 7 November 1941, in which troops marched out of Red Square to fight the Germans who had advanced to Moscow’s suburbs. Victorious wars are what the Kremlin wants Russians to remember.

Instead, it’s Russia’s liberals who are taking the lead in commemorating the revolution’s complicated legacy. ‘1917 was the most important year in Russian history,’ says Mikhail Zygar, one of the founders of the independent internet-based Dozhd TV. ‘It was the first time that Russia had an opportunity to become a democratic republic. It was the highest peak of Russian culture, of Russian civil society.’

Zygar has created ‘Project 1917’, which recreates the events of a century ago with daily Facebook posts taken from contemporary letters, diaries and eyewitness accounts. It makes for fascinating reading. The revolutionary firebrand Leon Trotsky posts that he is en route from Madrid to Barcelona to take a ship to New York. ‘The scenery is ever more lovely. Kitchen gardens verdant — in December!’ The poet Alexander Blok muses that ‘life is proceeding in a silly, disagreeable, awkward, unlovely way. On rare days, things aren’t bad, but the rest of the time everything’s disjointed, discordant and petty.’ The painter Nadezhda Udaltsova posts her latest cubist still life. Even Grigori Rasputin — the venal Siberian holy man in whom the hapless imperial couple placed their faith — has been resurrected as a chatbot. Ask the bot what the future holds for Russia and it will reply with real quotes from Rasputin’s letters. ‘Thy strong word conquers all,’ opines the holy man, warning of doom gathering over Holy Russia. ‘None will escape!’

Its Facebook posts can appear lighthearted, but Project 1917 makes a deadly serious point. The Russia of a century ago was a ferment not just of political upheaval but of social and artistic experiment, a place where many of the formative ideas of the 20th century were forged. At the launch of Project 1917 at the Tretyakov Gallery in November, young actors mingled with guests and whispered or declaimed the words of the period’s radical geniuses — the women’s rights pioneer Alexandra Kollontai, for instance, and the Futurist poet Vladimir Mayakovsky. The point is that the brilliant, kaleidoscopic genius of Diaghilev, Chekhov, Stanislavsky, Malevich, Kandinsky, Nijinsky, Rodchenko and their revolutionary generation holds an accusing mirror to the dull, conservative and stifled Russia of today.

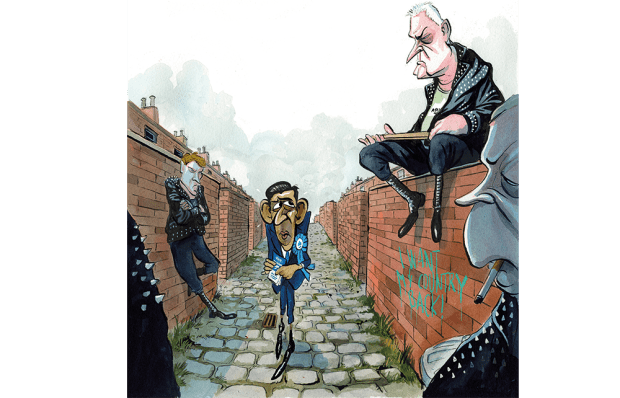

Indeed, Putin’s Russia in many ways resembles the kind of country that the White Guard would have built had they, not the Reds, won the Russian Civil War. Putin’s social conservatism, his use of the church to grant his rule legitimacy and his intolerance of dissent are an updated version of the Tsarist-era formula of ‘autocracy, Orthodoxy and the will of the people’. Boris Yeltsin may have reversed the revolution by overthrowing the Communist party. But it’s Putin who has brought the century’s circle back to its beginning. Putin has restored Holy Russia: a society where ruler and church are united, where dissent is treason and where secret police watch for the slightest flicker of popular discontent.

It’s no surprise, then, that official Russia will avoid glorifying 1917 — and not just because of the political dangers of encouraging revolt and protest. A century ago, Russia’s avant-garde represented the boldest concentration of imagination and talent in the world. They invented the future in which we now live. Today’s Russia, by contrast, lives in a cloud of nostalgia for a lost Soviet past. There’s no place in Putin’s vision of a united, obedient, God-fearing people for either revolution or radical thinking.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in