A United Kingdom is based on the greatest love story you probably didn’t have a clue about. I know I didn’t. It’s based on the true story of Seretse Khama, heir to the African kingdom of Bechuanaland (now Botswana), and Ruth Williams, a typist, who fell in love in 1940s London and married despite everyone and everything trying to separate them, including a vicious colonial British government. But this, sadly, is not the greatest film about the greatest love story you didn’t have a clue about. It’s OK. It does the job. It’s serviceable. It won’t be the biggest disappointment in your life. The story’s too good for it to get away completely. But it’s simplistic, exposition-heavy, joyless and focuses on the obstacles to their love rather than the love itself. I was begging throughout: come on, come on, give me something to feel.

The film is directed by Amma Asante (Belle) with a script by Guy Hibbert (Blood and Oil, Eye in the Sky) who, it has to be said, is not averse to cliché (‘You left as a boy and must return as a man’) or having people tell each other what they would surely already know. (At one point, the British prime minister has to be told: ‘We need South Africa to save us from Stalin.’ Personally, I would worry about a prime minister who hadn’t worked that out for himself.)

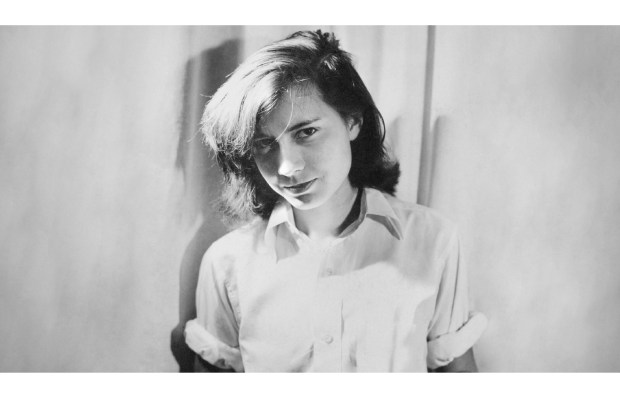

The film opens in London in 1947, when Seretse (David Oyelowo), who is a law student, and Ruth (Rosamund Pike) first meet at a London Missionary Society dance. Their eyes lock. He asks for a dance. They discover a mutual love of jazz. They go on a few bland dates. It’s hard to see why they might consider each other so special, but perhaps she fell for Seretse’s neat line in exposition, as in: ‘I grew up with my little sister. My mother and father died when I was three. I was raised by my uncle. He has been on the throne for the last 20 years…’ He proposes (in front of Big Ben, natch). She is wooed by yet more exposition: ‘My education is complete so now I must return…’ And accepts.

Naturally, she incurs hostility from her parents, who had not guessed who was coming for dinner, but that’s the least of it. Bechuanaland is a British protectorate and the British won’t allow it. Ruth is visited by Alistair Canning (Jack Davenport), a British diplomat and proper nasty bit of work who tells her a biracial marriage will offend South Africa ‘which is seeking to implement apartheid’ — we’ve yet to get to Stalin — and she must call it off. But the couple cannot be dissuaded and make for Botswana, where I imagined the story would seriously take off. What would Ruth, a lower-middle-class girl from Blackheath, make of Botswana? What would she make of the heat, the dust, the food, the wildlife, the poverty, the sanitation? Will she miss her family? What will the humidity do to her hair? But there is nothing about any of this. She is simply required to stand by her man and look perfectly groomed while Seretse’s family hate on her until the inevitable moment when they don’t, and the orchestra plays. (FYI, the end titles indicate Ruth was much more than this; you would do well to look her up.)

Much of the film is then taken up by the political ramifications which, in fact, have less to do with the marriage than with Seretse’s desire for his country’s independence. The British turn nastier, and have him exiled, such that he’s living in London while Ruth is still in Botswana. The two can now talk only occasionally on a crackly phone line, which is a bit of drag, dramatically. And the machinations continue. This diplomat is involved, then that diplomat. Churchill says one thing, then another. Seretse’s uncle, can he be won over? Unlike, say, a Peter Morgan script, the film does not take its lead from its characters and instead becomes the Big Book of Historical Bits We Thought You’d Best Know About, Dummy.

It’s not without interest. And the racism of the time will properly blow your mind. But it is never intimate. There is one lovely moment where Ruth practises the wave she has in mind as her queenly wave, but otherwise it is utterly humourless too.

Yet all is not lost. Pike is watchable in pretty much anything, which is helpful, while Oyelowo offers a performance that is sincere if not nuanced. (Not his fault; he isn’t given any nuance to do.) And it’s a story that can’t get away completely. Such courage. Such bravery. Such love. If only we could feel it.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in