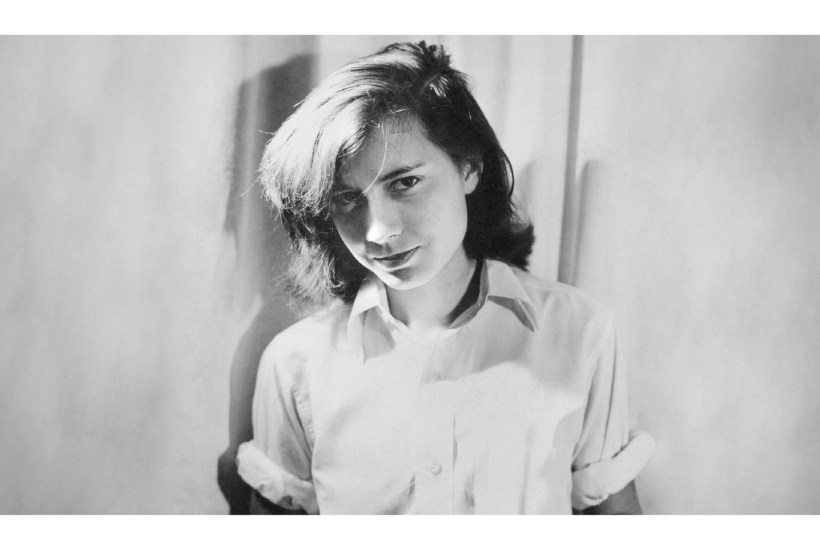

I first discovered writer Patricia Highsmith (Strangers on a Train, Carol, the five Ripley novels) as a young teenager working my way through Golders Green Library. I guess she came shortly after Georgette Heyer, and I was hooked. I only later became aware of her virulent anti-Semitism, and on this count she was not half-hearted – she called the Holocaust ‘the semicaust’ as it failed to fully deliver – yet I still could not look away. I’m the same with the spiders at the zoo: horrified, but also mesmerised. We must, I suppose, separate the art from the artist as not everyone can be Paul McCartney, but any Highsmith documentary should surely indicate that she was as disquieting and difficult and complex as the people she invented, yet Loving Highsmith refuses to go there, alas.

This documentary film is by the Swiss filmmaker Eva Vitija who wants, I think, to reframe Highsmith as a gay icon, and a romantic, with a soft side as a counterpoint to, say, the editor Otto Penzler who once described her as ‘a mean, cruel, hard, unlovable, unloving human being’. Vitija sets up her stall immediately by saying as the film opens: ‘Like many other filmmakers, I was drawn to her writing and when I read her unpublished diaries I fell in love with Highsmith herself.’ Not that unlovable, then..

The story is told via excerpts from her diaries (read by Gwendoline Christie), archive footage, clips from the best-known Hollywood screen adaptations, and a visit to extended family still living in Texas where Highsmith was born, even if they seemed to know little. Mostly, it’s Vitija telling them things while they exclaim: ‘Oh, shut up!’ The main talking heads are Highsmith’s lovers, like the writer Marijane Meaker, who is particularly good on Highsmith’s mother, Mary, a sinister narcissist and ‘bitch’ who was appalled at having a child and told her daughter she’d tried to abort her by drinking turpentine when pregnant. She refused to accept that Highsmith was a lesbian and even once found her a boyfriend. It didn’t go too well. ‘It wasn’t pleasant having to kiss him goodnight,’ Highsmith would write. ‘It was like falling into a bucket of oysters.’

Highsmith was closeted, as you would have to be at that time – she was born in 1921 – but promiscuous, always falling madly in love, swapping countries to be with the object of her affection. But nothing ever lasted. What was this pattern? Was she actually loved? Could she love? This stops short of any true psychological insight and omits the trickier parts of her character, like the anti-Semitism – ‘If the Jews are God’s chosen people – that is all one needs to know about God,’ she wrote to one friend – or the fact that two of her lovers were Jewish, which surely shows how extraordinarily conflicted and self-loathing she was. Meaker, in her own memoir, doesn’t shy away from it. During their last encounter she told Highsmith: ‘You’re like someone with obsessive compulsive disorder. You can’t go for long without mentioning the Jews, just as someone has to compulsively wash their hands.’ She’d had enough of it, but none of this is mentioned here, despite Meaker being front and centre.

The more you already know about Highsmith (Andrew Wilson’s biography is especially good), the more you will note the omissions but it’s still interesting because she was so interesting – she ended up living reclusively with her pet snails; Hortense was her favourite. Furthermore, her novels are so finely crafted that, even though her characters are often despicably repulsive (hello, Tom Ripley), the way the moral ground slowly shifts means we end up colluding with them, hoping they get away with theft, deceit, murder. She wrote in her diaries: ‘I learned to live with a grievous and murderous hatred very early on,’ and it’s this murderous hatred that is key. She may even be nothing without it.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in