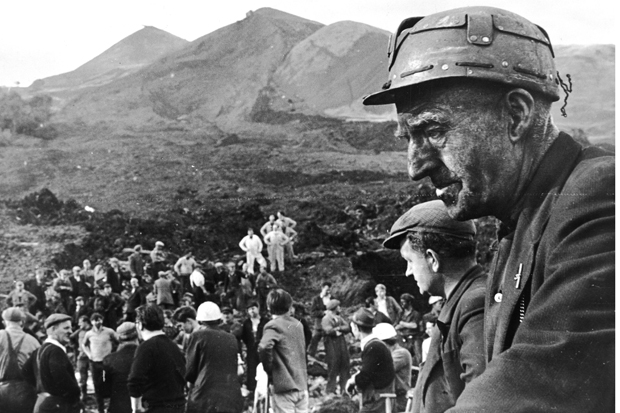

‘I went in at seven and came out aged 22,’ said Brian as he looked back on the day in October 1966 when his primary school in Aberfan was smothered in a great black wave of coal slurry. On that day, of his small school of just 141 pupils, only 25 children survived. Brian lost his older sister; he escaped because he refused to get under the desk as the teacher instructed when they heard this extraordinary, unexplained, overwhelming noise, ‘like an aeroplane coming into land’, getting louder and louder. He later joined the Ynysowen Male Voice Choir, formed in Aberfan a couple of years after the disaster as the fathers, husbands and brothers of those who died began to realise that the only thing that was helping them get by day-to-day was singing.

Brian was talking to the Welsh singer Max Boyce, who began life as a miner in a neighbouring valley and on that day in 1966 tried to reach Aberfan to help with the rescue attempt only to find all roads into the village were gridlocked. In The Voices of Aberfan on Radio 2 (Wednesday; produced by Kelvin Brown) the men of the choir explained to Boyce how they discovered that singing was a better way of getting over what had happened than talking. ‘You concentrate on the song and it makes you feel happier,’ they told Boyce. ‘It’s a community thing.’ There’s also no better way of letting the emotion out. ‘You can pour it all out without people knowing…’

We heard lots of their singing in this sad but uplifting programme; singing that was so powerful in its unity, its subtle harmonies, and yet surprisingly soft-toned and vulnerable at the same time, the moods swiftly changing within each song, emotions rising and falling as the words, and the baton of their female conductor, dictated.

Monica Vasconcelos, a singer born in Sao Paolo but now living in London, has also discovered the power of singing. In Losing My Sight and Learning to Swim on the World Service (Wednesday) she explained that just like her brother before her she is losing her sight to the disease retinitis pigmentosa. She asks her brother to take her out walking through the busy streets of London to help her learn how to use a white cane. She writes a song celebrating sunshine, even though she now has to hide from it because in bright light she really cannot see. She also recalls her meeting with the writer and neurologist Oliver Sacks not long before he died.

He recommended swimming as a way of sidestepping disability because when he was in the water he didn’t feel deaf or blind (he was blind in one eye and with cataracts in the other) or old, ‘I just felt the joy of swimming.’ Vasconcelos is not so sure about swimming but begins to understand that when she sings she is the same person as before the disease took hold. She is a singer, and a journalist, and she’s blind and a woman. All of these things are true, all define her; no one thing is true.

Music was also the backdrop of Nina Plapp’s Journey of a Lifetime on Radio 4 (Friday). Plapp grew up in a family that always played music together and their house was full of violins. She became intrigued by gypsy music, which is also so closely bound up with family and community, and decided to take Cuthbert, her grandmother’s 167-year-old cello, on a journey to Transylvania and further back to India in search of Romany families who could teach her how to play like them.

She takes out her cello on the train to Jodhpur for an impromptu recital and then, at an all-night goddess festival somewhere in the deserts of Rajasthan, she is put on a peacock throne and asked to join in with Cuthbert in the camel song. It’s wild and untamed, a wailing and yearning that’s unmistakably Eastern. But she feels right at home because the experience comes from the same source, like playing with her grandmother and aunt on the Isle of Wight.

The current Book at Bedtime on Radio 4 has been a masterclass on how to make a radio programme. First choose a good book — Jane Rogers’ Conrad and Eleanor — strong narrative, vivid characters and a twist of the unexpected. Next make sure the abridgement/adaptation, by Eileen Horne, serves the novel well, capturing its atmosphere and giving us enough time to appreciate its value, precise and pacy yet always clear and vivid. Now select your readers carefully (Robert Glenister, Penny Downie and Jasmine Hyde) to reflect that carefully constructed atmosphere, their slightly breathy, hectic delivery cranking up the tension as they take us inside the minds of Conrad and Eleanor as their marriage begins to unravel. Finally, make sure the production (by Clive Brill), with its weird electronic beat echoing through the soundscape, persistent and sinister, an ever-present reminder that something is not quite right and must be addressed, is smooth and classy, drawing us in so that it’s impossible to move even an inch away from the radio. Four stages, each vital for success, and dependent on experience and the time to ponder and create.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in