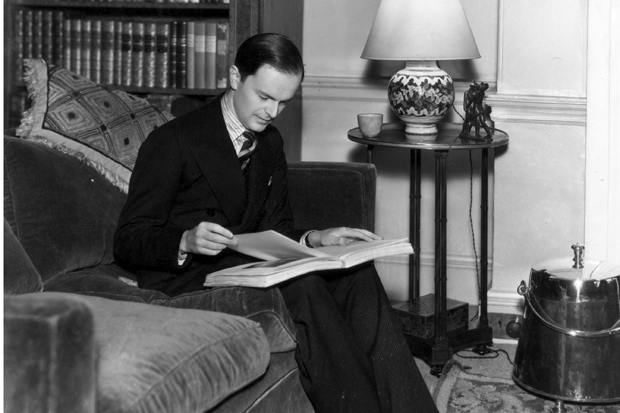

Our collective attention spans may not be as short as is widely cited, but they are pretty short. Take the case of the art historian Kenneth Clark. If anyone remembers anything about him, it is as the presenter of Civilisation, a TV series of the 1960s that rocketed him to stardom, and the author of the accompanying book, which sold over a million copies. He died in 1983 when he was a mythical figure, and any attempt to show his human dimensions was anathema, as I discovered to my cost. My own biography of Clark was published a year later.

Nowadays, one can hardly get anyone to take him seriously. One reviewer dismissed Civilisation as a period piece, the narrator ‘a patrician’ in a tweed suit. Another spoke of ‘a figure of derision’. He was ‘the great arts panjandrum’, said a third. The word means a powerful figure but also a pretentious one — a snob.

Nobody reads his first volume of autobiography, Another Part of the Wood, any more, and so no one has understood what special qualities of mind invigorate his works, though they are clear enough on the page: honesty, insight, humour and a complete lack of self-importance. He described his parents as the idle rich: ‘Many people were richer, but there can have been few who were idler’. He introduced their competing temperaments: an emotionally blocked mother and grandly alcoholic father. ‘He put up with her bouts of self-pity and she devoted her whole life to an unsuccessful attempt to stop him drinking.’

They might have been, as Clark said, ‘as ignorant as swans’, but they recognised their gifted son’s love of art. Their innate understanding of his career path was at odds with their colossal ignorance of his emotional needs. His mother glided through his life like a somnambulist. She was reading in the library one day when she smelled smoke, so she got up and moved to another room. Shortly after, the floor fell in.

Clark claims she never touched him. Correct that to ‘seldom’ — Stourton shows a photograph of her with an awkward arm around him; he looks equally uncomfortable. He was brought up by servants and by Lam, an understanding governess whom he loved.

He also loved his father, but there was a price to be paid. He told me that,

whenever they were in London, his father’s bouts of drunkenness would become unusually heavy. ‘He would stagger into the lobby of a hotel, or his club, and collapse on the sofa.’ People would complain, and,

I’d have to go and get him into a cab. A porter and I between us would get him up to the flat. My father wasn’t an angry drunk, just an incapable drunk. I couldn’t explain to people what a dear old boy he was really, and I felt terribly embarrassed and never got over it.

Among the challenges Stourton had to face is the biographer’s eternal conundrum: how to convince the reader of the accomplishments of his subject. He has done this brilliantly, not only exploring his gifts as author, lecturer, film-maker and champion of British art but also as public figure. He takes pains to show the reader Clark’s human dimensions, and his impish sense of humour. I saw this trait at close quarters.

One day K, as he liked to be called, and I were waiting in the car while K’s second wife Nolwen made a stop at her dressmaker’s. She was taking too long. K took over. He rolled up a piece of newspaper, got out of the car and started walking around the neighbourhood, which contained more than its share of chained dogs. The barking reached fever pitch. Nolwen ran out, full of apologies.

As a former chairman of Sotheby’s, the author is naturally interested in Clark’s career as a public figure: director of the National Gallery, work with the Ministry of Information in the second world war and efforts to mould the Independent Television Authority after it. I would say, a bit too interested. Do we really need to know about Clark’s influence on the trustees of the British Museum’s policies in 1968?

One wishes, too, that Stourton had spent more time considering the effect on Clark of the accident of fate that gave him an alcoholic father, an alcoholic wife, Jane, and an alcoholic son, Colin. Surely K had puzzled over this, but he seemed too easily satisfied with excuses. He said of Jane, ‘I asked her about it but she said she liked to drink.’ On another occasion, he said that he had tried to probe, but ‘she bit my head off’.

It is possible that he felt an uncomfortable sense of guilt. His factotum, Mr Lindley, once gave K a report on Jane after he picked him up at the station. She had been in fine fettle during K’s absence and had not ‘touched a drop’. K replied searchingly, ‘You mean it’s my fault then?’

His son Alan presented other problems. It is true that his volatile mother took a dislike to him. Alan retaliated by hating her back, at considerable emotional cost, as can be discerned in his diaries, particularly the later ones. ‘She became the enemy,’ he told me. I remember he said it with no apparent emotion, but he was hugging himself. ‘I flinched when she touched me.’ What did his father make of this antagonism? It is hard to tell. Colette — Colin’s twin — recalled that, during these rows, her father would send them loving glances but did not intervene. He acted more like ‘a child among us children’. Alan’s hatred never wavered. When Jane lay dying he said, ‘Why doesn’t she get on with it?’

What layers of affection, need and obligation lay behind Clark’s long marriage to Jane, which was punctuated by so many affairs, is another unanswerable question. In his own way, he found a bearable solution. Jane, sober, could be intolerable; but when drunk her mood changed and she became wistful, Ophelia-like. Mr Lindley saw him on his way to her bedroom with her first drink of the day every morning.

I fully expect that this assiduous and accomplished biography will bring about a second Great Clark Boom. In the meantime, a correction: publicity for the book claims this is the first biography of Kenneth Clark. It isn’t.

The post Special K appeared first on The Spectator.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in