One of the charms and shortcomings of biography is that it makes perfectly normal situations sound extraordinary. According to Michel Winock, Gustave Flaubert (1821–80), the author of Madame Bovary and L’Éducation sentimentale, contracted ‘an early and profound aversion to mankind’. To Gustave the schoolboy, man was nothing but a coagulation of ‘mud and shit… equipped with instincts lower than those of the pig or the crab-louse’.

This might have been the influence of his freethinking father, an eminent Rouen surgeon, but perhaps it was just the spirit of the age. The Napoleonic adventure was over; the sun of Romanticism had set. As Winock reminds us, quoting Alfred de Musset’s Confession of a Child of the Century, ‘the young saw the foaming waves ebbing away from them… and those oiled gladiators felt unbearably wretched’.

The depressing lycée which Gustave attended in Rouen can’t have helped: ‘Life at boarding school was harsh. The premises were poorly heated and rudimentary, hygiene left much to be desired; discipline was rigorous’ and ‘student insurrections were not uncommon’. Schools in biographies nearly always have an air of Dotheboys Hall about them. I taught at that school in 1979–80 and found it exactly as Winock describes.

Wallowing in lost illusions was normal for the time, as was the argot of scientific jargon and obscenities which Flaubert used throughout his life: ‘I feel waves of hatred against the stupidity of my era suffocating me. Shit is rising into my mouth, as with a strangulated hernia.’ Politics left him cold or, rather, seething with indifference:

The idea of la patrie, the fatherland — that is, the obligation to live on a bit of earth coloured red or blue on a map, and to detest the other bits coloured green or black — has always seemed to me narrow, restricted and ferociously stupid.

Like countless bourgeois teenagers of the 1830s, Flaubert decided to make the best of a bad job by becoming a writer: ‘Let us intoxicate ourselves with ink, since we lack the nectar of the gods.’ ‘What is surprising here,’ says Winock, ‘is not the attitude but its staying power.’ Flaubert’s last work, unfinished and probably unfinishable, was a Dictionnaire des idées reçues. To judge by what survives, it would have taken the form of a conversation manual for fools: ‘ENGLISHMEN: All rich.’ ‘ERECTION: Said only in reference to monuments.’ ‘FRANCE: Needs an iron hand in order to be ruled.’ Flaubert’s hope was that readers of his ‘encyclopedia of human stupidity’ would never dare say anything again in case they ‘inadvertently uttered one of the sentences in the book’. It might have been subtitled, ‘World, Shut Your Mouth’.

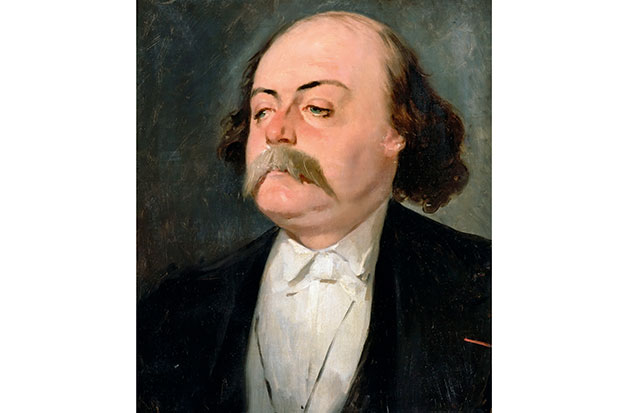

‘Why write yet another biography of Flaubert?’ asks Winock in his opening sentence. For that matter, why write a biography of Flaubert at all? He spent almost his entire life sitting in a summerhouse above the Seine, fuming at the stupidity of the human race, and writing — which is to say, filling up the wastepaper basket and salvaging an occasional sentence — for 14 hours a day. When he looked up, he saw the masts of invisible ships passing on the river and, on one occasion, the Obelisk of Luxor on its way to Paris. That was Flaubert for nine-tenths of his waking existence — ‘a big, stout, superb Gaul with an enormous moustache, a powerful nose, and thick eyebrows sheltering a seabird’s blue eyes’, dipping his pen in an inkwell shaped like a frog.

Luckily for his biographers, he travelled quite a lot, notably to Egypt, where, like many an ‘artistic’ young man of the time, he tried out sodomy. He told a friend after a visit to the baths in Cairo, ‘It was a laugh, that’s all. But I’ll do it again. For an experience to be done well, it must be repeated.’ (‘Expérience’, that faux ami, should obviously be ‘experiment’.) He also contracted syphilis, as did ‘practically everyone’, according to the Dictionnaire des idées reçues. Nonetheless, as the narrator of Julian Barnes’s Flaubert’s Parrot puts it, he had ‘an active and colourful erotic career’. There are some detailed examples in his letters to the poet, Louise Colet; but we know almost nothing about his long affair or friendship with the English governess, Juliet Herbert, who translated Madame Bovary before it was published. (The translation, which Flaubert called ‘a masterpiece’, has disappeared.)

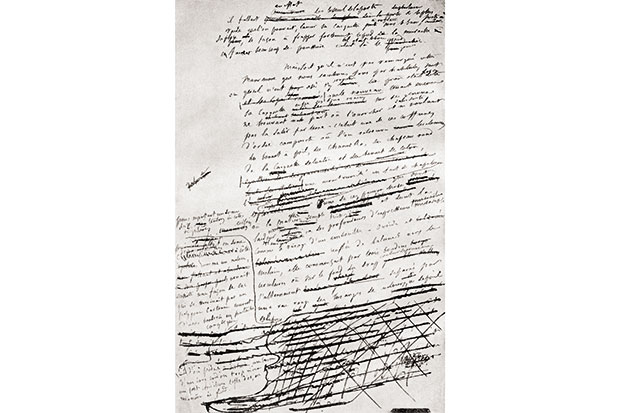

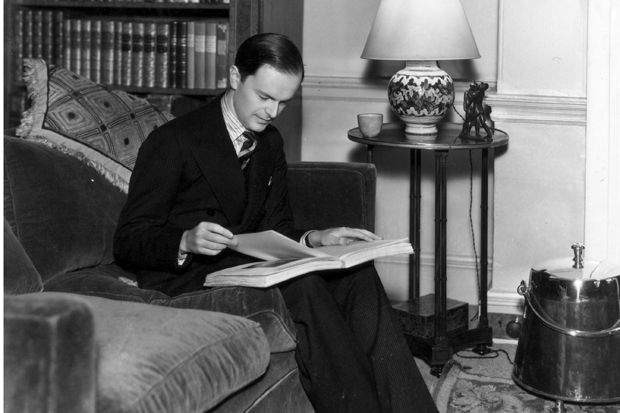

A page from the manuscript of Madame Bovary. Flaubert wrote for 14 hours a day, filling up the wastepaper basket and salvaging an occasional sentence. Above right: the ‘big, stout, superb Gaul with an enormous moustache, powerful nose and a seabird’s blue eyes’

A page from the manuscript of Madame Bovary. Flaubert wrote for 14 hours a day, filling up the wastepaper basket and salvaging an occasional sentence. Above right: the ‘big, stout, superb Gaul with an enormous moustache, powerful nose and a seabird’s blue eyes’

Later, there would be literary dinners in Paris and soirées at the court of Napoleon III and the Empress Eugénie. But at the end of each excursion, there is the closing of the writer’s door and the biographer trudging back down the garden path with a rueful glance at the study window. If only Flaubert hadn’t spent so much time writing…

Winock wrote this biography not because he had anything new to say, but because, as a historian, he wanted to depict ‘the life of a man in his century’. ‘It is a biography written for pleasure.’ The problem is that to depict Flaubert as a man of his time is to return him and the reader to ‘the boredom and ignominies of existence’. By the end of the tale, Winock is tidying away the unhappy details — Flaubert’s epileptic fits, his money lent and lost — like an efficient executor. Chapter 25: ‘The Ups and Downs of Melancholy.’ Chapter 26: ‘Financial Ruin and Bereavement.’ Flaubert’s last English biographer, the scholarly and entertaining Geoffrey Wall, told me that he had been intending to omit Flaubert’s last months entirely until his publishers, objecting to this act of biographical euthanasia, insisted that ‘You can’t have a Life without the death!’

To his credit, Winock devotes a great deal of space to Flaubert’s letters and novels, and this is really the main point of interest in any Flaubert biography. In the 1830s, sensitive young people commonly wanted to grow up (or not grow up) to be writers. In 2015, a YouGov poll found that 60 per cent of British people would like to be an author. Those 38 million people might find some useful advice in Flaubert’s correspondence. Live like a bourgeois and think like a demigod. Recite your sentences at the top of your voice to test their harmonies and cadences. To impart an erotic shimmer to your romantic scenes, first write a brazenly pornographic version and then purify it. This process, akin to burning the brandy off a Christmas pudding, seems to have worked well in Madame Bovary: its author was prosecuted for obscenity, but then acquitted. The prosecuting counsel remarked on the absence of ‘any gauze or veil’ in M. Flaubert’s ‘lascivious’ descriptions; but he evidently found it hard to put his finger on any explicit lewdness.

Flaubert is often described as a writer’s writer; but students of creative writing should be warned that he is not a would-be writer’s writer. This biography gives a good sense of the unrelenting misery of composition: ‘grinding away at it, digging into it, turning it over and over, rummaging about in it’. Flaubert was referring here, not to a whole book, but to a single sentence. Over four afternoons and evenings, his friends listened in silence while he recited his Temptation of Saint Anthony, which had taken three years to write, and then told him that it should either be completely rewritten or thrown on the fire. This is perhaps not what writers’ groups call ‘mutual support’, but it was an impressive act of kindness. The final version, published 25 years later, was much improved. When his first published book, Madame Bovary, finally appeared in 1857, he felt the embarrassment and humiliation of seeing himself in print:

I noticed only the misprints, three or four repetitions … one page with an abundance of the word ‘which’ — as for the rest, it was black, and nothing more.

Biographies inevitably consist entirely of significant details. Flaubert’s novels —whether the subject is adultery in the provinces or the hallucinations of a third-century saint in the Nitrian Desert — are memorable for what Roland Barthes called their ‘futile details’: flies buzzing in empty cider glasses in a farm kitchen, the sound of branches brushing the roof of a carriage, a dog barking in the distance. Among all the exasperating trivia of a world governed by fools, there were beautiful, meaningless mysteries which only the excruciatingly slow extrusion of perfect sentences could reveal.

The post Intoxicated with ink appeared first on The Spectator.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in