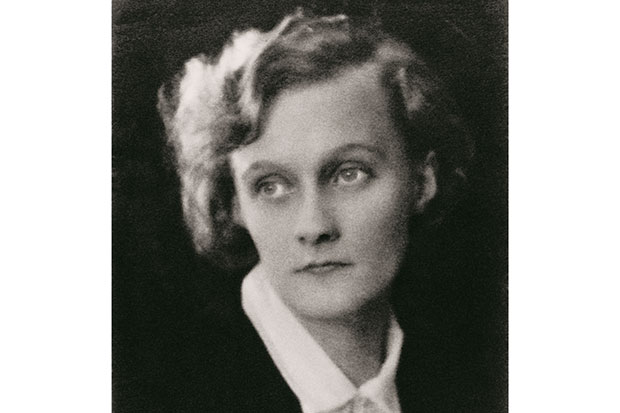

There’s a glorious scene in Astrid Lindgren’s first Pippi Longstocking book in which her fearless, freckled heroine strides to the centre of a circus ring and briskly lays out the World’s Strongest Man. Like most of the adults who expect to control her, he quickly learns that his inflated size, age and title are no match for the child’s bold pin-wielding attitude.

As a little fan myself in the early 1980s I probably giggled as the strongman toppled. But reading it to my own children this summer I also felt a deep lurch of sadness. The strongman’s name was Adolf, and the book (published in 1945) was written as an equally ridiculous Adolf was sending train loads of bright little Pippis to their ‘final solution’.

As a housewife in neutral Sweden, Lindgren could only strike back through fiction. But the diaries she kept during the war reveal the full extent of her frustration at living in a country which continued to do business with the Nazi regime, giving access to German troops and supplying them with ball bearings. ‘A shocking history lesson’ is how the Swedish press described the diaries after they were published across Scandinavia last year, 13 years after the author’s death, at the age of 94. Now translated into English by Sarah Death, they make for crisp, painful and perspective-refreshing reading. We’re so accustomed to our own, retrospectively glorious national war narrative that we can be guilty of forgetting the dilemmas faced by others.

I remember my GCSE history teacher’s easy contempt for Sweden’s neutrality — they didn’t fight the baddies with us! But Lindgren’s diary reminds us that this was a small nation, sandwiched between the aggressive armies of National Socialism and Bolshevism — ‘two giant reptiles doing battle’. For all she despised the Nazis, there’s a moment in 1941 when she prays they will defeat the Russians,

given all they have grabbed for themselves in the course of this war and all the harm they have done to Finland. In Britain and America they have to side with Bolshevism, which must be ever harder and I’m sure the man in the street finds it hard to keep up with it all.

Lindgren had a broader view than the average woman in the street. With her two children at school, she took a job as a censor in the state’s secret Postal Control Division, gaining rare access to the private and military correspondence that crossed Sweden’s borders. Reading the stories behind the propaganda of all stripes, she is exposed to the private human suffering of every race and nation in ‘a world gone mad’. She embarks on a serious quest to understand the psychology behind the Holocaust, but ends by laying aside the wordy academic pamphlets and throwing up her hands. ‘Surely the God of Israel must intervene soon!’ she writes in March 1941. You can hear her inner Longstocking in the simplicity with which she asks: ‘How can Hitler think one can treat one’s own fellow human beings like that?’

Each fresh horror Lindgren absorbs deepens her guilt at the relative luxury which she and her family enjoy. June 1943 finds her transfixed by a photograph purporting to show a bombed out Italian maternity hospital and agonising over the reported starvation of ‘sixteen hundred Greeks a day’, while the Swedes chow down on ‘lots of meat and bacon’, and celebrate the lifting of fish rationing. That Christmas, the Lindgrens’ fridge contains ‘two big hams, liver paté and pork ribs, herring salad, two big pieces of cheese and some salt beef. Beside that, my tins are full of home baking: ginger snaps, oat biscuits, brandy rings, almond fingers, gingerbread and meringues.’ Every complaint about her kids — her son’s failed exams and her daughter’s persistent cough — are couched in concessions about how lucky she is to have such minor domestic concerns.

Like many Swedes, Lindgren did her best to help the suffering when she could. An entry from 1939 finds her up in the attic, parcelling up clothes to send to Finns, including coats and some ‘gruesome’ knitwear belonging to her mother-in-law. ‘Though I think the Finns already have enough trials without Mother’s cardigan.’

While her diary reveals a clear effort to keep tabs on the big picture — she pastes in maps, speeches and newspaper cuttings — its pleasures lie in her beady eye for detail and humour. She chuckles as the Russians interpret Churchill’s V sign as an intention to start a war on two fronts.

World statesmen are sketched with the deft purity of characters from children’s fiction. There’s an echo of Lewis Carroll’s White Rabbit in the tribute she pays Neville Chamberlain on his death in November 1940. She regrets that the ‘nice old gentleman who was always running late’ had also been ‘too late’ to learn that ‘being nice wasn’t enough’ to stop Hitler. She hopes that ‘God will give him a nice little place in Heaven — “blessed are the meek” — where he can sit under his umbrella undisturbed’.

Although the Lindgrens all survive the war physically unscathed, there are hints of marital discord, and 1945 sees Astrid taking time off work for anxiety and insomnia. Luckily she had begun writing the ‘jolly, funny’ adventures of Pippi Longstocking for her daughter Karin in the winter of 1944, while laid up with a sprained foot. Christmas 1945 sees her celebrate ‘literary success’, with the real Adolf on the mat, like his fictional counterpart.

At the circus Pippi Longstocking waves aside the prize money she is offered for knocking out the Mighty Adolf and tells the pompous ringmaster to go and wrap fish in it. A relieved Lindgren, likewise, finds it hard to celebrate ‘the fall of a major country’. ‘“The leader fell at his post of command”,’ Donitz said. Sic transit gloria mundi.’

The post A bit player in the great drama appeared first on The Spectator.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in