You have to imagine the lines that follow in separate fonts to get the full sense of the nonsense in ‘Karawane’, one of Hugo Ball’s ‘verses without words’:

jolifanto bambla ô falli bambla

grossiga m’pfa habla horem

égiga goramen

And it ends not with a bang, but with … ‘ba-umf’. See the original and it’s impossible not to be impressed by the industrial-strength madness of Ball’s absolute certainty.

His poetics of nonsense claimed to drain words of meaning, but quite the opposite effect was achieved. The meaninglessness is itself meaningful: cognition is on an infinite loop. Sense or nonsense, Ball intended to show that ‘this humiliating age has not succeeded in winning our respect’.

So, in the middle of this, our own humiliating age, it’s nice that the centenary of Ball’s Dada movement is being commemorated in a series of events, performances and exhibitions in Zurich. In his novel Flametti, or the Dandyism of the Poor (whose subject is a libidinous circus troupe) Ball cites the ‘laughable impotence’, ‘stupendous smugness’ and ‘self-evident limitedness’ of politics in 1916. If any of this sounds familiar in 2016, it proves that self-destructive Dada actually has enduring values. It was not a style, but a state of mind.

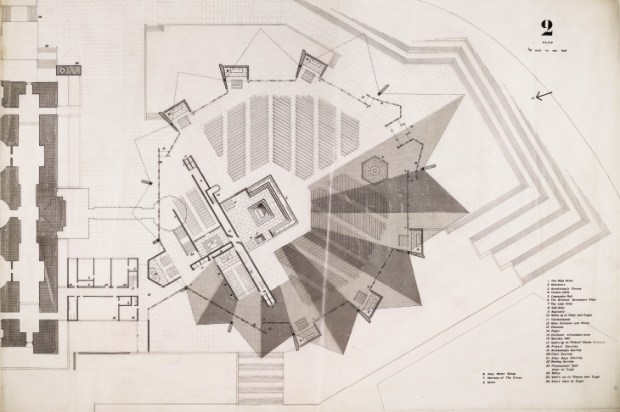

They say that in law-abiding Switzerland what is not forbidden is compulsory, but in 1916 Zurich was a liberal refuge from the horrors of war. This was the year of Gallipoli, the first Zeppelin raid on Paris and the final version of Einstein’s baffling general theory of relativity. And in Zurich, the Cabaret Voltaire opened on 5 February at Spiegelgasse 1 in a back room of the Holländische Meierei pub. This was the spiritual home of the Dadaists, an incontinently irreverent rival to the established Café Odeon whose customers included the altogether more sober James Joyce, Lenin, Einstein and Stefan Zweig.

It is absolutely fitting that the anarchic Dada has confused etymology. Some said it was from the Russian for ‘yes, yes’ (Cabaret Voltaire was near Lenin’s apartment). But ‘dada’ is also French for rocking horse. A local soap company called Bergmann & Co. used a rocking horse as a trademark and since one group manifesto portentously proclaimed, ‘Dada is the best lily-milk soap in the world,’ that, too, might be an explanation. But explanation is bourgeois and the Dadaists were not.

The personnel reveal something of the movement’s character. Hugo Ball was a dramaturge from Munich who liked getting dressed up in geometrical cardboard outfits. His wife was a chanteuse and when the couple became disenchanted with Dada’s descent into absolutely unfathomable nonsense, they left Zurich for Ticino and became interested in mystical Catholicism and best buddies with Hermann Hesse.

Romanians were prominent in Dada. Marcel Janco was an architectural student at Zurich’s important Eidgenössischen Technische Hochschule, but set aside functional things to perform poems in a simultaneous babel of German, French and English. His party piece was ‘L’amiral cherche une maison à louer’. Then there was Tristan Tzara, born Samuel Rosenstock. He was the catalyst of the group and its busiest publicist: Tzara advocated cutting words out of newspapers, shaking them up in a bag and assembling the result into a hopefully meaningless poem. And don’t forget Hans Arp, a friend of Kandinsky’s. Only in the bizarre context of Dada could the citation of Kandinsky’s name suggest orthodoxy. Meanwhile, Arp’s wife, Sophie Taeuber-Arp, performed cubist dances. Her portrait is now on the Swiss National Bank’s 50 franc note.

The shouty silliness of the Cabaret Voltaire and the pranks of the Dadaists (who would rush into the Café Odeon and shout ‘Dada!’ at a bemused Lenin or Zweig) would be only a very small footnote in the history of art were it not for the influential diaspora from Zurich. Ball and Tzara were adroit communicators: news of nonsense travelled fast and made good copy.

In Berlin, local Dadaists supported Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht in the 1918 uprising. In Elterwater in Cumbria, Kurt Schwitters built his Merzbau — an undefinable amalgam of collage, assemblage and architecture — in a rustic barn. ‘Merz’ is a fragment of the word ‘Commerz’, which Schwitters found in a newspaper and made his motif. Schwitters is the gold standard of collage. Dada also gave us photomontage and in the compositions of John Heartfield this technique turned anti-war propaganda into a densely effective medium.

But it was in New York that Dada became most memorable. Marcel Duchamp emigrated to Manhattan in 1915, bringing the Dada sensibility of art-as-attitude with him. Depending on your point of view, Duchamp is either one of the last century’s most important artists — a witty magus who felt the pulse of his historical moment and, with great art, changed the history of art — or an attitudinising charlatan, scoundrel and shameless publicity hound. My own view tends towards the former, although, this being Dada, either interpretation might be true.

The notion of a ‘readymade’ work of art is the ultimate expression of the Dada sensibility and the ultimate readymade was Duchamp’s urinal, exhibited in New York in 1917 as ‘Fountain’ and signed, in drippy autograph, ‘R. Mutt’. Anything you want to think about ‘Fountain’ is true. Taking the piss? Of course! Anticipating the valorisation of the industrial object which, as ‘design’, became, with rock’n’roll and movies, one of the great cultures of the 20th century? Absolument! A satire on consumerism, a critique of art-world amour-propre, a modern vanitas portrait? Naturally. The invention of appropriation? Too damned right! An argument about authenticity in art that predicts Walter Benjamin’s great essay about reproductions? Most certainly.

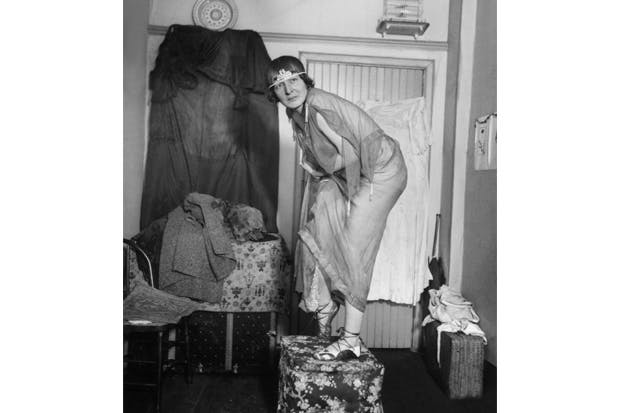

I could go on, but recent research suggests that Duchamp was not actually the source of ‘Fountain’. Instead, it is now being credited to the Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven (née Plötz), the subject of an unfinished biography by Djuna Barnes. The baroness was a performance artiste, a multisexual kleptomaniac and scatologist in whose cheerfully obscene poetry we find coinages such as ‘Phalluspistol’ and ‘Kissambushed’.

She called Duchamp ‘M’Ars’ which, it was explained, stood for ‘My arse’. In an act of pure Dada, she accidentally gassed herself in Berlin in 1927, but not before publicly wearing tomato-soup cans as a bra, presenting herself hither and yon half-naked, shaving her head and lacquering it with red enamel and, just days before Marcel ‘created’ ‘Fountain’, sending him the porcelain pissoir signed with the Mutt nom-de-plume that was, in fact, her own. Only in the 1950s did Duchamp begin authenticating versions of it and these are what we find in various museums around the world.

In a mess of confusion, Dada disappeared up its own bullhorn in 1923. The following year André Breton published La Révolution surréaliste, which gave pictorial form to the nonsensical dreamworld declaimed from the stage on Spiegelgasse. As for Cabaret Voltaire, the premises fell into desuetude and were occupied by situationists, scroungers and traditional squatters, but it reopened in 2004. Ba-umf.

Dada has a place in the history of nonsense that begins with Lewis Carroll’s ‘slithy toves’ and matures into Alfred Jarry’s play Ubu Roi, whose first word is ‘Merde!’ Opposed as it was to what Duchamp called ‘retinal’ experience, it did, perhaps, not create great beauty, but it changed the way we see the world. And that’s one definition of true art.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in