Anthony Neilson is an Arts Council favourite known for trivial but impenetrable plays with off-putting names like The Wonderful World of Dissocia. His latest effort has another hazard-warning instead of a title. Unreachable starts with an actress auditioning for a dystopian sci-fi movie set in a clichéd future. She lands the role and we cut to the film-lot where more clichés await. Pretentious director Max is furious because the sun won’t stay in one place and he decides to ditch his digital cameras and film instead on old-fashioned celluloid. The shoot is suspended while producers scrabble around for emergency funding. This self-involved storyline would be unbearable if it weren’t for the charming whimsicality of Matt Smith as Max. He develops a minor crush on his leading lady, whose cynical attitude to her trade is coolly refreshing. ‘If you want me to feel something, pay me.’ Their dialogue has flashes of coarse wit. The actress claims to dislike babies because ‘they cry, suck tits and shit themselves’. Max says he knows thesps who do little else. The psychological details of the characters begin to fall into place. Max was raised as an orphan and his tantrums are a ploy to win him the emotional reassurance he needs. He’s mothered by his executive producer (Amanda Drew), who relies on the lead cameraman for rough-sex liaisons that are kept scrupulously secret from Max. These layers of intrigue and manipulation are all too realistic between close colleagues. The script seems to be settling down as a cheerful backstage comedy when Max makes a fatal decision.

He hires Ivan (also known as ‘the Brute’), who surges up through the floorboards like a cherubic madman, his blond locks stiffened with hairspray, his shirt ripped open to the waist. Ivan is an ungovernable heap of pretention whose Slavic name and German accent recall the ghost of Klaus Kinski. He boasts that he arrived on set having walked barefoot for 30 miles, pausing only to seduce a mother and daughter in a passing caravan. He curses all films as ‘vomit’ and ‘sewage’ and he detests anyone who labels Hollywood ‘an industry’. ‘Coal mining and steel,’ he bellows, ‘are industries. This is a slaughterhouse.’ Last time Ivan worked with Max, they ended up hunting each other on horseback through a forest teeming with mantraps. Now they embrace as brothers and promise to create a masterpiece. Within hours Ivan is calling Max a ‘cathedral to mediocrity’ whose films are travesties of beauty and truth created by philistine investors to make yuppies ‘crawl out of their shelters’ for a brief interlude of wretched escapism. When Ivan falls unexpectedly in love, he reveals a gentler side to his egoism. He boasts that he hires only ‘the oldest and ugliest streetwalkers’ out of pity for their fading looks. He never eats vegetables because he’s haunted by memories of his father’s allotment. ‘I heard their screams as he tore them from the ground.’

The play becomes lopsided towards the close as it evolves into Ivan’s solo show. But I’m not sure this matters. The Brute is a role every actor would kill to play. And it’s a flight of rhetoric every play-goer will queue to see again and again. On press-night Jonjo O’Neill was operatically brilliant as the swivel-eyed monster and yet he was self-indulgently careless as well. He corpsed twice, quite openly, and his fellow actors seemed not to mind this atrocity. They even joined in. My hunch is that they’ve grasped the nature of this project. They’re merely inaugurating roles that future actors will develop and extend for years to come. That’s how good it was. The birth of a classic.

Fury is a snapshot of a Peckham tower-block where incoming toffs mingle with the native underclass. Sam is a drunken single mum who fancies Tom, a rich country boy studying for an MA. But Tom turns out to be an amoral blackmailer who agrees a pact with his victim. He will keep quiet about Sam’s assaults on her small boys provided he gets to rape her.

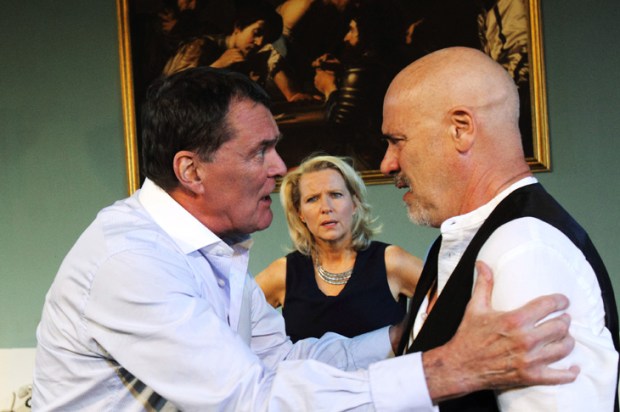

Fury at Soho Theatre (Photo: The Other Richard)

Every character in this part of Peckham is criminally malevolent. Sam’s ex-boyfriend declines to support his sons as he needs money to sire more fatherless kids. An old pal of Sam’s arrives offering friendship but the overture sours. ‘Dirty little bitch,’ she tells Sam. ‘I hate you so much.’ Three social workers show up and accuse Sam of prostituting herself and of failing to wash her sofa-covers. And they turn their pious aggression on the audience. ‘Who’s the monster here? Her? Him? Us?’

The good news about this witless cage fight is that the author is sitting on a gold-mine. Shows like EastEnders are constantly in need of these turgid cockney quagmires. And they pay a fortune to anyone willing to dredge up the bilge.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in