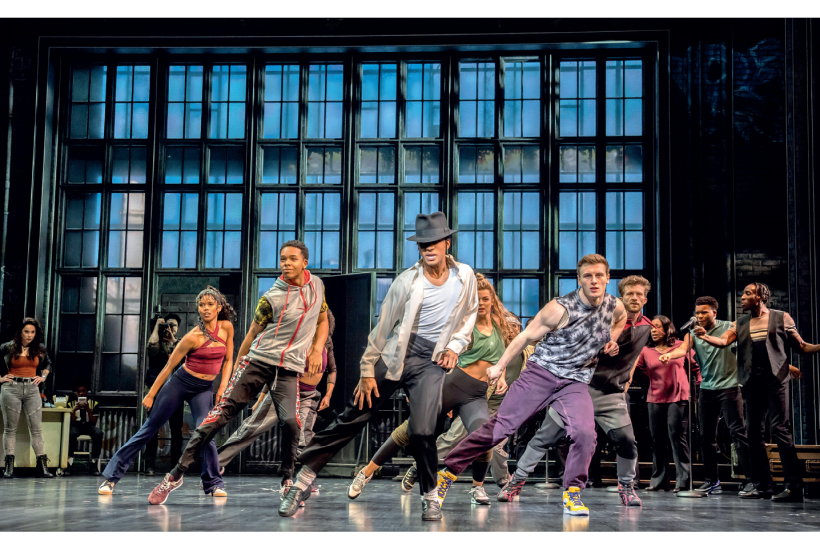

If you’ve heard good reports about MJ the Musical, believe them all and multiply everything by a hundred. As a music-and-dance spectacular, the show is as exhilarating as any Jackson produced while he was alive. The sets, the costumes, the choreography and the live band deliver an amazing collective punch.

When he removes his black trilby he looks like Rishi Sunak at a karaoke bar

The script, by Lynn Nottage, takes us into Jackson’s twisted personal history. He was one of ten children raised in a four-room shack in Gary, Indiana, by weirdo parents. His mother was a Jehovah’s Witness who refused to celebrate birthdays or Christmas. His father, Joseph, didn’t share his wife’s Christian beliefs and he poured all his energy, and all his wages from the local steel-mill, into his talented sons. He was a failed bluesman whose band, the Falcons, never got a break so he transferred his ambitions to the Jackson Five. He was a violent disciplinarian and he feared that his sons might end up as bums – or worse – if he didn’t give them a strong work ethic. He bullied Michael about his looks and called him ‘pizza face’ and ‘big nose’ in front of his brothers. These taunts led eventually to Michael’s destructive obsession with plastic surgery.

When the boss of Motown saw the Jackson Five he recognised Michael’s talent immediately. ‘That kid is lit from within,’ was his famous verdict, although in this show he says, ‘that kid is out of this world’. The band’s success coincided with the arrival of colour television in America and the production celebrates the lurid psychedelic colours of that era. The boys perform in matching purple jumpsuits with flouncy orange shirts flaring from their chests like bursts of sunlight. The costumes from the 1990s look tame and drab by comparison.

MJ is played by the astonishing Myles Frost, who matches the vocal firepower of his subject and brings the same intense and ferocious energy to the dance floor. His only defect is his Napoleonic stature and when he removes his black trilby he looks like Rishi Sunak at a karaoke bar.

Frost also shows us Jackson’s eccentric behaviour off-stage. He speaks in a whispery, itty-bitty voice but he’s very demanding and he forces his team to push themselves ever harder to realise his vision. Money means nothing to him and he’s happy to re-mortgage Neverland to raise funds for the extravagant stage effects he wants for his shows. Even during ordinary conversations, he dances non-stop because he has too much spare energy to burn.

In part he’s driven by his desire to outdo his rivals in the world of pop. He orders his artistic director to try out a new idea because ‘it came to me in a dream from God and if we ignore it, God will offer it to Prince’. In the history of art it’s rare for a creator to have both the freedom and the money to deliver everything that his imagination demands. Jackson was in that unusual position and this production shows us his creativity in action.

Fans of gossip will be disappointed that the show overlooks the child abuse allegations and Jackson’s difficult marriages to Lisa Marie Presley and to Debbie Rowe. But a dramatisation of his entire life would last longer than the complete works of Shakespeare. This is a fantastic starting point.

A dramatisation of Jackson’s full life would last longer than the complete works of Shakespeare

There are two views of Dostoevsky. One is that he’s a purveyor of profound political insights and the other is that he’s a garrulous, overrated sentimentaliser. His admirers will have countless reasons to applaud Laurence Boswell’s gripping dramatisation of his short story, The Dream of a Ridiculous Man, which has been updated to modern Hackney. The narrator is a rootless depressive living in a boarding house crowded with noisy refugees. The walls are so thin that he can hear the junkies next door snoring. He owns nothing but a suitcase, a few books and a revolver, which he uses to mime his impending suicide. One night he dreams of an island paradise whose inhabitants are so happy that the concepts of ‘God’ or ‘the afterlife’ mean nothing to them.

Open-air copulation is normal in this steamy tropical realm, and the vices of romantic jealousy or sexual frustration are unknown. Young couples pair off and stay together for life, apparently. But the idyll is broken by the arrival of sexual shame along with deceit and violence. And the story develops like the fall of Adam and Eve. The narrator advises us that love can cure our wicked natures – but only if lust is isolated and destroyed completely. That’s quite a tricky operation to pull off.

Before the narrator can explain how to deliver the panacea, his story comes to an end. This quietly spectacular son et lumière show will be loved by fans of Dostoevsky. But its brilliance may not be enough to turn the sceptics into devotees.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in