One could honour God with prayer, of course, and build cathedrals, amass treasuries, turn choirs into stained-glass jewel boxes, carve portals with saints and sinners. But for the medieval monks bent over vellum in chilly scriptoria colour, too, was devotion: offertories of lapis lazuli, azurite, cinnabar, silver and gold, gold and more gold. Silver tarnished on the page, but gold remained exquisite, inviolable, and monks and scholars found a dragonish greed for it.

War, weather, revolution, Henry VIII, Oliver Cromwell, acquisitive magpies, trophy-hunters and time have stripped gold and pigment from sculptures and ivories. Frescoes have been whitewashed, mosaics scuffed, stained-glass smashed, reliquaries melted and their gems dispersed, but illuminated manuscripts, bound between covers of oak and tanned leather, survive. They are the best record we have of the elation of colour in the art of the sixth to 16th centuries.

This elation is the subject of the Fitzwilliam Museum’s Colour: The Art and Science of Illuminated Manuscripts. The exhibition marries 150 manuscripts from the Fitzwilliam collection with new research from the Cambridge Miniare (Manuscript Illumination: Non-Invasive Analysis, Research and Expertise) project which, with infrared imaging, microscopic magnification and X-ray scanning, has identified the pigments and painter’s materials used by monks, scribes and professional artists in the illumination of their pages.

The contents of a scriptorium’s cabinet have something of the ‘eye of bat, toe of frog’ about them. The parchment pages are goatskin, sheepskin, calfskin, split and pared down to tissue thinness, or they are ‘uterine vellum’ — the skin of aborted calves. Cuttlefish bones scraped the parchment smooth. Quills were cut from goose, swan or crow feathers. Hair from squirrels’ tails made the finest brushes. Gold leaf could be polished to brilliance with a ‘dog’s tooth’ — a shard of agate.

Black pigments came from charred ivory or animal bones. ‘Sepia’ black came from the ink in cuttlefish glands. ‘Iron gall’ black from wasps’ eggs laid in oak trees. The Fitzwilliam’s ‘Portrait of René of Anjou’ (late 15th century) is an essay in modish black: iron-gall winkle-picker slippers, black hose, black doublet with billiard-ball shoulders, black hat with a broad black brim.

Green came from Russian malachite — a mineral — or from the unripe berries of a buckthorn tree. Their sticky juice yielded ‘sap green’, which was stored in a pig’s bladder.

Red could be had from the earth mineral minium (hence ‘miniare’ — to write or paint in minium, which by the 16th century gave us ‘miniature’ for small paintings on parchment). Red also came from cinnabar, vermilion and mercury. The Roman taxonomer Pliny, a collector of both natural histories and far-fetched fables, writes of a red pigment called ‘dragon’s blood’ derived from the mingled bloods of a battling dragon and elephant. While most pigments could be had from the town apothecary, a scribe wanting to get his hands on dragon’s blood would have to wait for a defeated dragon to be crushed beneath a wounded elephant. Spoilsport art historians have since identified ‘dragon’s blood’ as the sap of the East Asian rattan palm tree.

Purples, sometimes ‘mollusc purples’, came from sea snails. Pinks came from the ground shells of kermes insects (kermes gives us ‘crimson’) and, after the discovery of the Americas, from cochineal insects.

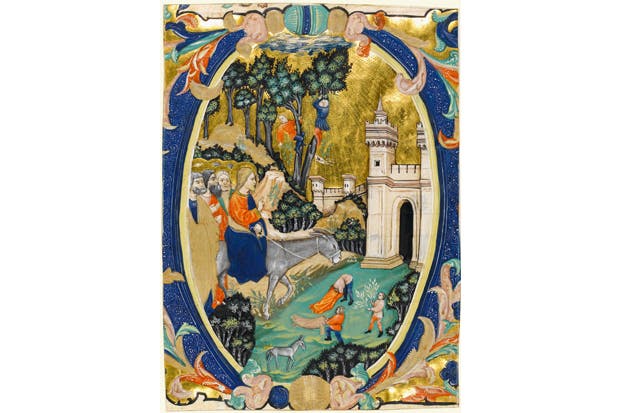

Ultramarine, most precious of colours, sometimes painted in a thin wash over cheaper azurite, came from lapis lazuli, shipped across the seas from Persia and ground with a stone muller on a porphyry slab. It is rare to find a Virgin without her ultramarine robes.

Yellow came from orpiment, derived from arsenic crystals, or from saffron, which while expensive (around 150 crocus flowers are needed to make an ounce of dried saffron) had the virtue of not poisoning the painter. A highlight of the Fitzwilliam’s exhibition is a St John’s eagle (early 8th century) from Lindisfarne, feathered in verdigris green, red lead and yellow orpiment. He would make a splendid Christmas ornament.

But why have yellow, when you could have gold? This came to the workshop in thin, flyaway sheets. Sneeze and the leaves would be lost. Gold leaf was laid over areas of parchment brushed with fish glue or beaten and strained egg whites.

All colour, but blue and gold most of all, was expensive. One 13th-century youth, sent to study at Bologna and Paris, was chastised by his father for frittering his allowance on illuminated books ‘enbabooned with gold letters’. That is, explains Professor Paul Binski, a Cambridge medievalist: ‘monkeyed up’ at vast expense.

Scribes and illuminators were not always sticklers for nature. One finds blue-rinsed St Matthews with lapis-dyed ringlets, moustaches and beards, and flocks of livestock that have fallen into vats of mollusc purple. In one early 12th-century Bury Bible there is an ultramarine ox, a purple goat and a pair of crimson boar. In another St Matthew’s Gospel (c.1200) from St Alban’s, Matthew sits on a Technicolor dream throne constructed like a great layered Victoria sponge: yellow at the bottom, then pink, then blue, then pink again, then yellow with little quatrefoil cut-outs, then dark green, pale green, white and a top layer of red sugar icing.

When scribes do get the naturalism bug in the 14th century, they paint with the exactitude of the botanist. Millefleurs scroll along page edges ripe and blooming with wild strawberries, daisies, poppies, thistles, dandelions, roses, fungi, forget-me-nots, and attendant wagtails, goldfinches and lapwings, all in their proper colours.

Borders and margins become places of mischief. Below a stately visitation — ultramarine Mary, greeted by mollusc-purple Elizabeth — a lion pads snackishly towards a desert hermit. The corners and bases of pages are mayhem: a hare plays a church organ, woodcutters foot-wrestle, a monkey scratches his bottom, a timorous knight is menaced by a snail, a squire in a popinjay tunic — purple, crimson, verdigris — rides the bare back of a wild man.

Left: detail from ‘The Maastricht Hours’, Liège, 14th century, and ‘Les Grandes Heures du Duc de Berry’, Paris, 1409

Left: detail from ‘The Maastricht Hours’, Liège, 14th century, and ‘Les Grandes Heures du Duc de Berry’, Paris, 1409

These margin varlets now enjoy a unlikely social media afterlife on Twitter. Monkeys, monsters and jesters are cropped from their manuscripts and sent as online emoji. Instead of tweeting the silly-face, tongue-lolling smiley you can send the three-headed beastie from the Saint-Denis missal with its sausage-dog body and knotted, spotted turban. ‘International Yoga Day’ was celebrated on Twitter with twisting acrobats from the Rutland Psalter and ‘World Oceans Day’ with two jousting knights on swordfish steeds from a British Library folio.

At the Fitzwilliam a game of I-spy in the margins is irresistible: spot the man-dragon in his lapis-blue Wee-Willie-Winkie cap, the archer taking aim at a minium red bird, the dog pumping cinnabar bellows. Here is colour to praise God, colour to boast a monastery’s riches, colour to beautify bare margins, to beatify the Virgin, to breathe life into Gospels, to cry havoc at the edges of the page, and colour for its own irrepressible sake.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in