Sport has never held much appeal for me, so I rarely venture into stadiums. But I do appreciate their peculiar power: I was present at the 2012 Paralympics when George Osborne ill-advisedly turned up to award a medal while engaged in a campaign against disability benefits, and was roundly booed by the entire stadium. It was a transporting lesson in the joy of crowds and the proudest I have ever felt to be British.

The stadium, ostensibly a facilitator of mass spectatorship, is actually a machine for producing such feelings. The Greeks were explicit about the ritualistic, community-forming function of their games, but it was the Romans who secularised the stadium and gave it its current form. The Greeks could look beyond the terraces to the sacred landscape of Olympia, whereas in the Colosseum all the spectator saw was a wall of fellow spectators, replacing the natural backdrop with a social one.

Make of that change what you will, but when it comes to stadiums, we’re still living in the world the Romans made. That goes for what we do in them, too, whether it’s football tournaments such the Euros currently under way in France, or the Olympic games shortly to begin in Rio — or executions, as in the Santiago stadium where Pinochet killed hundreds of his opponents.

The Olympics may be Greek in derivation but their architecture and ethos are not. These belong to our era of nation states, masses and spectacle. There were no modern gymnastic arenas before Pierre de Coubertin revived the Olympics, and although the stadium for the inaugural Athenian games in 1896 was modelled on the Greek hippodrome, this turned out to be utterly inappropriate. Runners had to decelerate to take the tight bends and the field in the middle of the track had the dimensions of a large hall rug.

For a long time, attempts to fit all the events into one arena continued, resulting in vast spaces — the one for the games at the 1911 Turin International World’s Fair covered 85 hectares — where the distant athletes were like microbes in a Petri dish. However, these buildings now looked more like the Colosseum than any Grecian ruin. The Nazis settled on a more sensible solution in 1936, when they erected a compact stadium in a park full of other facilities. Although we have largely abandoned tiered arches, we continue with the Nazis’ sports-park typology, erecting ever more expensive stadiums at their centres, from Kenzo Tange’s fantastic concrete forms for the 1964 Tokyo Olympics, to Herzog and de Meuron’s Bird’s Nest in Beijing.

There have been efforts to reign in this extravagance. Otto Frei’s diaphanous canopy for Munich is barely there at all (it shelters only a third of the spectators), and our own stadium for the 2012 Olympics, designed by specialist architects Populous, was supposed to be the most lightweight ever constructed. This wasn’t cheap, and the freshly circumcised building’s occupancy by West Ham has been highly controversial. But at least it will get regular use.

One of the most expensive elements of the Stratford stadium has been the roof, which is now the largest cantilevered covering in the world. Putting a lid on a stadium is an engineering challenge of the first order, and one that has seen numerous solutions, from the elegant concrete cantilevers of Italian engineering genius Pier Luigi Nervi to the completely covered Houston Astrodome. The latter kept everyone dry but the light coming through the dome dazzled the players, and when the plastic panes were painted to make them semi-opaque the grass on the pitch died. It was replaced with a new invention named after the building: Astroturf.

Besides getting the size and the roof right, the other big problem faced by stadium builders is crowd control. The current record for stadium capacity is held by North Korea’s Rungrado Stadium, which seats 150,000 beneath its attractively scalloped covering. As well as sporting events, Rungrado is used for the adulatory mass spectacles favoured by the regime. In the late 1990s it was also used for the immolation of several generals accused of plotting against the dear leader.

Efficiently accommodating so many people in one building is a challenge that became something of a mania for modernist architects. A double-decker stand had been tried at Arsenal’s Highbury ground in 1932, and this approach was adopted at Feyenoord in Rotterdam, opened in 1937. The steel-framed structure was designed by Johannes Brinkman and Leendert van der Vlugt, who had recently completed a famous factory, and they took a similarly industrial approach to the stadium, which was optimised for processing its human contents as rapidly as possible — it could disgorge its 64,000 spectators in a matter of minutes.

Disaster constantly lurks in the back of stadium builders’ minds, and the designers of Feyenoord felt they had to prove the integrity of their innovative structure by inviting a crowd to bounce on it as a sort of test run. People had reason to be sceptical, since a stand at Ibrox Park designed by Britain’s most prolific stadium builder Archi-bald Leitch had collapsed in 1902, killing 26 spectators.

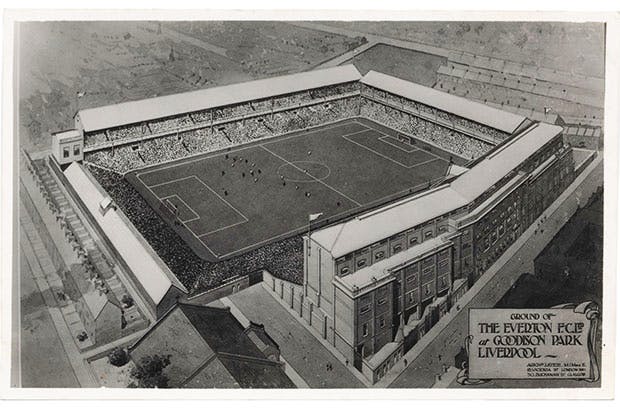

This didn’t do Leitch’s career any harm, and he went on to build more than 20 stadiums around Britain. Like Brinkman and Van der Vlugt, Leitch had begun his career designing factories, and he took a similarly no-nonsense approach to his stadiums, for all their charming Edwardian façades. This traffic between builders of factories and stadiums speaks of the link between mass labour and mass leisure in the industrial era, where regimented spectacle was produced in buildings similar to places of work. This nexus would reach its dark apotheosis when serried ranks of workers were taught to cheer a different sort of hero in the stadiums of Nazi Germany.

The inherent bloodthirstiness of stadiums is barely masked by the ritualised combat of modern sport. The Romans used theirs for barbecuing Christians, and Ghazi Stadium in Kabul was the Taleban’s favoured stoning venue. Stadiums have also been the scene of many accidental deaths, leading, after the Hillsborough disaster, to their reform, with capacities reduced and terraces replaced by seats.

This transformation also catered to the televisation of sport, which required a sanitised product suitable for home consumption. As a result, Camiel van Winkel observes that stadiums have become ‘little more than outgrown television studios’, with terrace camaraderie obliterated by fear and profit.

The backdrop demanded by TV spectaculars is a sort of high-tech banality, as attested by the recent crop of stadiums in London and Rio. But there is a glimmer of something stranger and more exciting on the horizon: Herzog and de Meuron have designed an intriguing project for Chelsea FC, the wispy renderings of which suggest a monstrous brick spider mounting Archie Leitch’s original building. Let’s hope it lives up to the drawings.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in