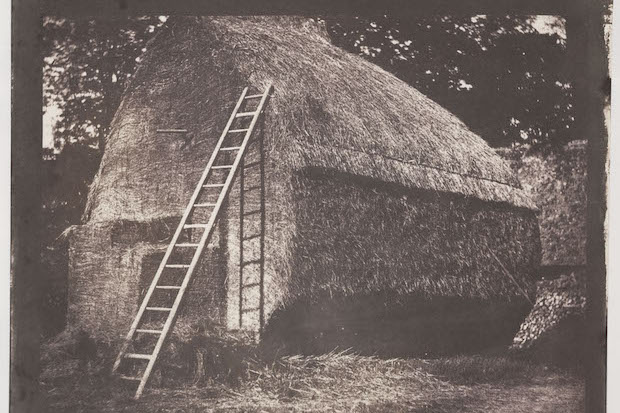

William Henry Fox Talbot had many accomplishments. He was Liberal MP for Chippenham; at Cambridge he won a prize for translating a passage from Macbeth into Greek verse. Over the years he published numerous articles in scholarly journals on subjects ranging from astronomy to botany. One thing he could not do, however, was draw well — and it was this inadequacy that changed the world.

Already a subscriber? Log in

Subscribe for just $2 a week

Try a month of The Spectator Australia absolutely free and without commitment. Not only that but – if you choose to continue – you’ll pay just $2 a week for your first year.

- Unlimited access to spectator.com.au and app

- The weekly edition on the Spectator Australia app

- Spectator podcasts and newsletters

- Full access to spectator.co.uk

Or

Unlock this article

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in