Is there a more extraordinary, more heart-stilling moment in all opera than the finale of Mozart’s The Marriage of Figaro? The Count, suddenly understanding his wife’s fidelity, begs her forgiveness — ‘Contessa perdono!’ Her answer comes like a musical benediction, but not until after the very slightest pause — space to doubt, to hope. It’s a touchstone for any production, and it says everything about the current revival of David McVicar’s long-lived Figaro that, on press night, the audience laughed.

Since 2006, McVicar’s elegant period update — poised in the fragile political hinterland between France’s First and Second Republics — has done the business at the Royal Opera. But now on its fifth revival, the show is beginning to show its age. Tanya McCallin’s sun-bleached château sets are lovely as ever, and the Gallic Downton Abbey conceit, framing an intimate chamber drama with the silent goings-on of a whole household of domestics, still feels fresh, it’s just that the direction itself looks increasingly fossilised.

It’s not a question of neglect, rather that McVicar’s instinctively musical stage gestures have become too precise, too predictable. Mozart’s score is pure narrative, and when the visuals mirror that so closely the drama gets bogged down in the literal, echoing but not amplifying the score.

Then there’s the issue of dramatic balance. Too many times before we’ve seen the men dominate this production, throwing off the energy of Mozart’s intricate ménage with a Susanna and Countess so far from the equal of Figaro and the Count. Here, once again, Erwin Schrott’s practised Figaro is allowed to run the show, challenged only by Stéphane Degout’s superbly patrician Count. Anita Hartig’s Susanna (under-characterised; sweetly but anonymously sung) and Ellie Dehn’s too-light Countess barely make an impression, though a blistering Barbarina from Heather Engebretson is an unexpected delight and the addition of some serious sexual tension between Dehn and the wonderful Kate Lindsey’s urgent Cherubino adds welcome innovation.

But there’s no getting away from the brittle quality this production has acquired. At no point in the Upstairs, Downstairs shenanigans is the emotional anchor dropped. We laugh at the Count’s declaration because we simply don’t believe in his marriage. How can there be relief at the saving, or fear for the loss, of a relationship painted in such garish cartoon colours?

You probably get 50 Figaros for every production of Vaughan Williams’s Riders to the Sea or Holst’s Savitri that you’ll see in a lifetime — a not entirely unfair equation, on balance. While Vaughan Williams’s J.M. Synge adaptation about a mother doomed to lose all her sons to the sea (think Martin McDonagh, then take away the jokes) is an effective, if maudlin, miniature, Holst’s Savitri is a perfumed bit of Eastern silliness — a love triangle in which Death is a participant — redeemed only by some rather lovely vocal lines. It’s a bold choice of double bill for British Youth Opera, and one that places the perhaps too-heavy burden of carrying some flawed works on very young shoulders.

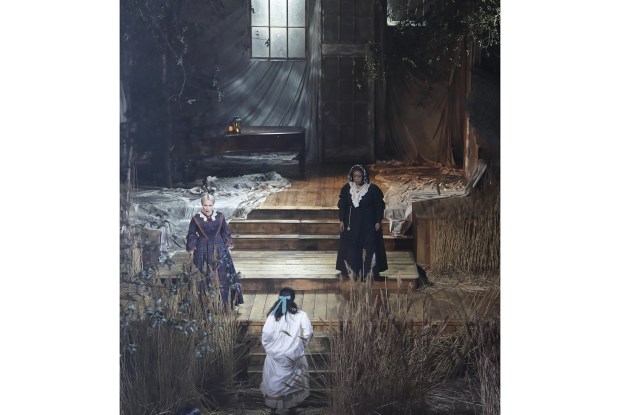

Riders is the more successful of the two. Director Rodula Gaitanou’s evocative production suspends us in a stylised, Brecht-lite scenario. Props and furniture for Maurya’s cottage hang from the ceiling, doubling characters held in their own stasis, mesmerised into inaction by the memory of their dead sons and brothers. Placing these (silent) figures as a constant presence on stage loads the dice, giving a focus and a weight to Maurya’s obsession — a centre of dramatic gravity constantly tugging at the single surviving son Bartley (a clear-voiced Huw Montague Rendall).

Strikingly mature, both vocally and dramatically, Claire Barnett-Jones’s Maurya is the centre to this maelstrom of musical grief. There’s a stillness to her performance that chafes effectively against the energy of Josephine Goddard’s Cathleen. All of which would add up to a more satisfying whole were it not for the thin and sometimes ill-tuned contributions of Geoffrey Paterson’s Southbank Sinfonia. The Peacock acoustic is a challenging one, but it’s hard to forgive such unsympathetic support for such excellent young singers.

The orchestral issues persisted more intrusively in the spare orchestration of the Holst, encouraging the singers to skim the surface of a score whose success depends on them diving deep into its long melodies. Matt Buswell’s Death was, however, a stand-out, whose charismatic intervention should, by rights, have seen Sofia Larsson’s Savitri carried off to his flowery kingdom. But only in tragedy does Death ever get the girl, and so, by the end of the second half the dramatic scores were even: Death 1: Life 1.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in