Jeremy Hutchinson was the doyen of the criminal bar in the 1960s and 1970s. No Old Bailey hack or parvenu Rumpole, he was the son of Jack, a distinguished practitioner in the same field, and Mary, a Bloomsbury Strachey. An Oxford undergraduate who acquired a criminal record along with a PPE degree (he accidentally shot a policeman with an air pistol), married first to Peggy Ashcroft, he moved throughout his life in the upper echelons of English liberal intellectual society, and was elevated, while still in practice, to the House of Lords. The brief biographical sketch at the outset of this book, littered with names of those whose paths he crossed, including T.S. Eliot, Winston Churchill, Isaiah Berlin and Roy Jenkins, sparks regret that Jeremy — as he has always insisted on being called — was too modest to write a memoir himself.

Happily Thomas Grant, also a barrister, found himself by chance the Sussex neighbour of the eminent advocate, now more than quarter of a century into his retirement, and spotted a reputation which deserved resurrection. In these case histories, stepping stones in his subject’s professional career, he has dwelt on trials involving sex scandals and espionage, sodomy actual and simulated (on stage and celluloid), and theft and fraud in the art world — all heady stuff for someone whose previous contributions to literature were textbooks on the worthy topics of lenders’ claims and solicitors’ negligence.

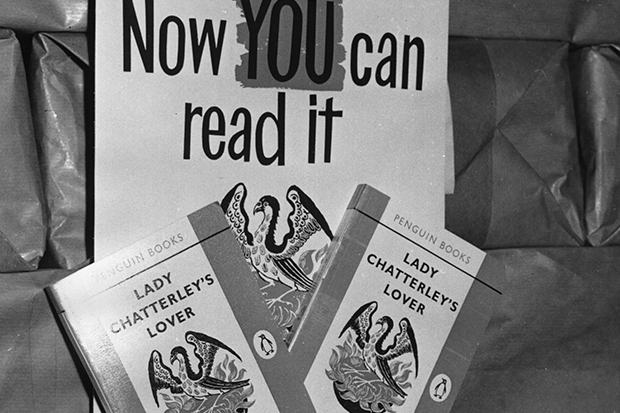

Many of Jeremy’s clients were as famous as his friends. They ranged from Stirling Moss (the charge inevitably one of dangerous driving) to Michael Oakeshott, the philosopher prosecuted for exposure when bathing naked off the Dorset coast, to Quintin Hogg, threatened with a charge of assault by a young liberal protestor. He successfully defended, as junior counsel to Gerald Gardiner, the publishers of Lady Chatterley’s Lover and, by then himself a senior silk, the distributors of Last Tango in Paris. (It is ironic that someone who made his reputation as a great defender and spokesman for penal reform, actually started his career, while still a member of the Royal Navy, by successfully prosecuting on a charge of murder an English sailor — a member of an outlaw gang of deserters who was duly executed by firing squad.)

Grant made his choice of 14 from hundreds of trials in which Jeremy was counsel. Many were of no interest (other than to those whom he so strenuously defended) ‘as a prism for the political, moral or cultural issues of the day’. Jeremy practised in an era when the main threats to society were seen as sexual unorthodoxy, obscenity and Soviet spies; when prosecutors were often partisan and judges seen as enforcers of establishment values rather than protectors of human rights. The day before yesterday seems a long time ago.

Advocacy is an art whose transient impact lies in the ear of the audience.There is necessarily no space in this book for anything more than extracts from Jeremy’s final speeches to juries or pleas in mitigation to judges. But the passages from his submissions on behalf of George Blake and Christine Keeler give the flavour of his forensic eloquence and courage, even if the style is more ornate than might pass muster in today cost-conscious courts. And what member of the profession would not envy his retort to the judge who used that weary phrase ‘I hear what you say’? ‘It is apparent that your Lordship hears what I say, but equally apparent that your Lordship has not understood a word of it.’

Renowned as much for the care of his clients as the skill he displayed in representing them, Jeremy was unusual in sometimes forwarding their interests outside as well as inside court, lobbying, letter-writing and, once an active peer, speaking up for them in the Lords.

Like many an advocate associated with good, brave causes, he was conservative in his attitude to the environment in which he flourished. The postscript to the book that he wrote in his 100th year is a jeremiad about the dangers to the very survival of an independent criminal bar and of the jury itself. Grant, a chancery lawyer, is naturally less familiar with such matters; but his comment that before the introduction of majority verdicts, ‘an individual juror wielded power to scupper.. acquittal’ would, had it been true, surely have prompted Jeremy to write an epitaph on rather than a valedictory to the English legal system.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Available from the Spectator Bookshop, £20 Tel: 08430 600033. Michael Beloff QC practises in a number of areas including human rights and administrative law.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in