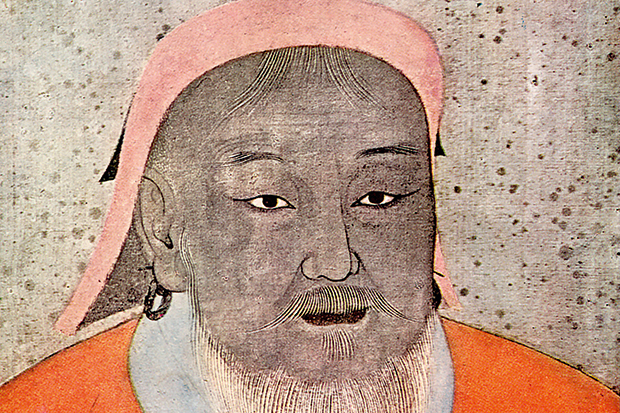

From the unpromising and desperately unforgiving background that forged his iron will and boundless ambition, Temujin (as Genghis Khan was named at birth) rose to build an empire that was to range from Korea and China, through Afghanistan, Persia and Iraq and eventually to Hungary and Russia, constituting the largest contiguous land imperium in history.

Already a subscriber? Log in

Subscribe for just $2 a week

Try a month of The Spectator Australia absolutely free and without commitment. Not only that but – if you choose to continue – you’ll pay just $2 a week for your first year.

- Unlimited access to spectator.com.au and app

- The weekly edition on the Spectator Australia app

- Spectator podcasts and newsletters

- Full access to spectator.co.uk

Unlock this article

Available from the Spectator Bookshop, £20, Tel: 08430 600033. Sean McGlynn is the author of By Sword and Fire: Cruelty and Atrocity in Medieval Warfare.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in