The award of a knighthood to the composer James MacMillan will have ruined last weekend for lots of unsavoury people: the Guardian arts desk, which decided he’d lost his mojo as soon as he turned his back on the left; Kirsty Wark, whose squawking is mimicked in MacMillan’s Scotch Bestiary; the SNP, which he detests; and, most of all, the Nats’ religious front organisation, the Scottish Catholic Bishops’ Conference.

OK, enough point-scoring. MacMillan has been honoured because he turns out glorious music. He’s also rare among living composers in having worked out an answer to the question raised when John Cage pushed sound to the point where nothing short of the soloist defecating on stage could shock audiences: ‘Where do we go from here?’

Lots of composers struggle with this. Minimalism was fun while it lasted, but when its creators tried to go mainstream they ran into trouble. Philip Glass’s Heroes Symphony is just Hollywood gloop with added chugging. Meanwhile, younger composers have also sought refuge in the past — which, for someone like Nico Muhly (b. 1981), is minimalism. How the heart sinks when, after two bold movements, the finale of his Cello Concerto turns into a cover version of John Adams’s The Chairman Dances.

Far worse are the impressionist tone poems that open concerts at the South Bank and the Barbican. Is it just me, or is this a speciality of composers from the Far East? I’m sick of hearing cod-Debussy with oriental seasoning provided by a pear-shaped Chinese lute. And don’t get me started on the disgusting cloying harmonies of Eric Whitacre and other neo-romantics…

But, as I say, the question of where to go is a tricky one. Looking backwards is fine; musical taxidermy isn’t. MacMillan has a strange genius for weaving textbook polyphony and raw folk music into his scores. Harrison Birtwistle, Oliver Knussen and, jumping a generation, Thomas Adès have their own clever ways of fusing past and present, though their styles are so personal that they could hardly be said to represent ‘the way forward’.

What about the ultra-modernists who, in their 1960s heyday, insisted that only the avant-garde mattered? Now they are severely out of fashion; even Radio 3 no longer indulges them. I imagine them locked in a conservatoire attic somewhere, one of them rattling the door handle while the others tape the noise and call it Anomie XVII or whatever.

These ‘squeaky gate’ composers are easy to make fun of. Brian Ferneyhough, born in Coventry in 1943, is leader of the ‘new complexity’ movement, whose arguments can only really be understood if you’ve got a maths degree. Plus, he looks like one of those orange-shirted Open University lecturers from my childhood. One of his most celebrated works is called Time and Motion Study II. I used to make jokes about ‘Uncle Brian and his toe-tappin’ tunes’ — until I actually listened to some Ferneyhough. Flurries for chamber ensemble may be an atonal scramble, but it bursts with joie de vivre.

Ferneyhough’s friend Michael Finnissy (b. Tulse Hill, 1946) is another famously tough listen. Sure enough, his Second String Quartet begins with ferocious scrapings but then settles into one of the most beautiful slow passages since Beethoven’s ‘song of thanksgiving’ in his Quartet Op. 132.

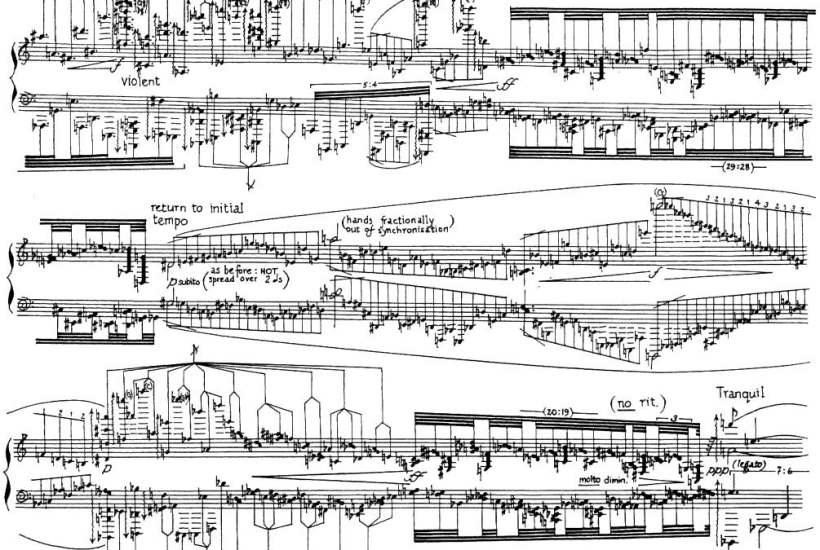

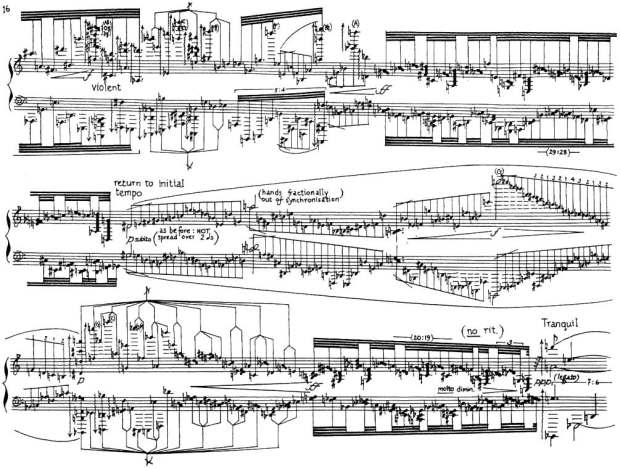

Now I’ve been given a recent recording of Finnissy’s History of Photography in Sound. It’s for solo piano and lasts five-and-a-half hours. It thus belongs to one of classical music’s least-known genres, the piano epic. There are only a handful of them, ranging from the perfumed ramblings of Sorabji’s four-hour Opus clavicembalisticum to the five-hour November by the early minimalist Dennis Johnson, described as ‘glacially static’ by admirers. A friend says you have to hear November live to grasp its power, but admits that he went for a McDonald’s halfway through and didn’t think he missed much.

Finnissy’s History needs to be heard in its entirety — though I haven’t found the time to do so in one sitting. It receives a supremely virtuosic and delicate performance by Ian Pace, who also wrote the 100-page booklet that comes with the CDs. If you listen to the History cold, you may be entranced by the way it drifts in and out of tonality. But Pace’s essay tells you what’s going on: the interplay of negro spirituals and hymns from 18th-century Boston; ‘mediated allusions’ to Rameau and Gounod; ‘austere derivations’ from a mixture of Bruckner and Chabrier; canonic patterns borrowed from Bach and dotted rhythms from Gershwin. These allusions are subtle, not ‘quotes’ that stick out a mile. Blink, let alone go out for a burger, and you’ll miss them.

The result is, I think, the greatest piano work of the 21st century so far. Finnissy, supposedly an uncompromising modernist, shows us how to mine tradition without resorting to pastiche. Other works have achieved that, but The History of Photography in Sound creates a template for future composers. If there is such a thing as ‘the way forward’, this may be it.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in