The British painter Nina Hamnett recalled that Modigliani had a very large, very untidy studio. Dangling from the end of his bed was a web inhabited by an enormous spider. ‘He explained that he could not make the bed as he had grown very attached to the spider and was afraid of disturbing it.’ This anecdote — in its combination of Bohemian squalor, fin-de-siècle strangeness, whimsical humour and delicacy of feeling — gives a few clues to the art of the man who slept in that bed.

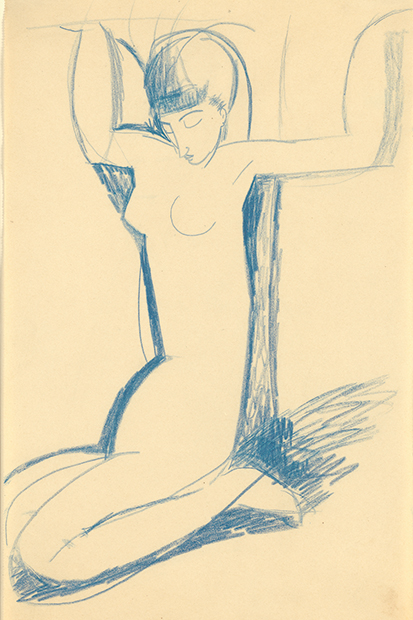

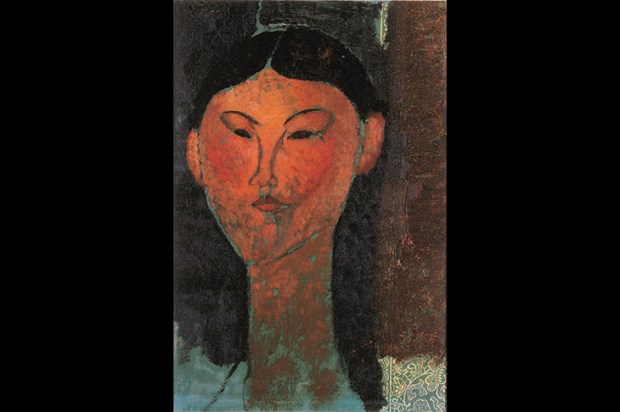

More are provided by a nicely focused little exhibition at the Estorick Collection, Modigliani: A Unique Artistic Voice. It is made up of 30 drawings — many from the earlier part of the painter’s short career, plus one painting, a portrait from 1918. Altogether it makes clear that the subtitle of the show, though a bit of a cliché, gets one thing right. Amedeo Modigliani was unique.

This is one of the puzzling aspects of his work. Although born and brought up in Italy, Modigliani (1884–1920) lived in Paris for most of his adult life. That spider-ridden bedroom was in Montmartre, where Modigliani was a contemporary of the Cubists and the Fauves. But, though surrounded by the explosive beginnings of modern art, he was not exactly a modernist himself.

Wit is not the first quality you associate with Modigliani, but there is something lightly but deliberately comic about many of these works on paper. Indeed, there are moments, when looking at his stylisation and touches of waspish humour, that the name Aubrey Beardsley comes to mind more than that of Pablo Picasso.

The tiny, pursed mouths and huge noses of the stylised heads he drew in 1911 look as much like Osbert Lancaster as ancient Greek sculpture. So, too, does the heavy-lidded and long-legged ‘Woman Reclining on a Bed’ from around the same time (identified as the great Russian poet Anna Akhmatova, with whom Modigliani had an affair).

At other moments, Picasso does seem relevant. ‘The Portrait of Cristiane Mancini’ (c.1917), drawn with the sparest of lines and not the slightest suggestion of shadow, closely resembles — even, though the dating is vague, anticipates — Picasso in his neoclassical mode.

The off-putting thing about Modigliani is the way he seems to make his sitters look the same: all those long necks and almond eyes. In 2006 I emerged from an RA show feeling he was a mannered, limited and repetitive purveyor of modernism lite.

This display of drawings is more engaging. It suggests his art was a complex mixture of elements — turn-of-the-century decadence, the influence of Egyptian, African and Cycladic Greek sculpture, a lyrical sense of line. Perhaps that’s what all unique talents come down to: an unusual combination of ingredients.

Another member of a tribe of one is the abstract painter Gillian Ayres, who is celebrating her 85 birthday in great style with an exhibition of new work at the Alan Cristea Gallery (for which, I should add, I have written a catalogue essay). As that birthday suggests, Ayres has had a long, long career which stretches back to the 1950s. More remarkable than that she has been working for more than six decades — especially for an abstract artist — is that she has avoided becoming trapped in a signature style.

As this gallery mini-retrospective at Alan Cristea demonstrates, in appearance her work has shifted greatly over time. The latest phase is exuberant and uplifting, full of juxtapositions of strong colours and simple forms that look effortless — and are tremendously hard to achieve.

Like Miró, a predecessor she admires, Ayres seems to have a vocabulary of private symbols — stars, spiky, Middle Eastern-looking flowers, shells, trees — but if they have meanings she isn’t saying what they are. The results don’t look like landscapes or still life. On the other hand, they do have what good abstract paintings always have: a sense of the world. In this case, it is a feeling of organic life, energy and growth.

‘It’s uplifting that an old artist is able to carry on like this,’ Ayres once said, ‘working on the highest level.’ She was talking about Miró, but the words now apply to her too. This one-room career overview is so powerful it suggests that some museum should hurry up and organise a proper retrospective of Ayres’s whole output.

Fiona Rae is also an abstract painter of an individual variety, though a much later generation than Ayres. Rae was born in 1963, and was once classified among the young British artists of the 1990s — a mixed bunch, with whom she did not have much in common except age and perhaps a certain pizzazz. The latest batch of her work, on show at the Timothy Taylor Gallery, is intriguing.

She has set herself the problem of making an image at the point of erasure or disappearance. The results, painted in a range of blacks, whites and greys certainly suggest something: if not a human figure, perhaps the debris of a birthday celebration — ribbons, wrapping and bits of glitter — floating in outer space. They are odd, but memorable and confirm the theory that complete abstraction is as mythical as the chimera.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in