Alexander McQueen famously claimed to have stitched ‘I am a c***’ into the entoilage of a jacket for Prince Charles. The insult was invisible behind the lining and his tailor master later investigated and found nothing. So what was this? An invention, an embroidery of the truth? It certainly became a good source of publicity as he spread the story — step one in the creation of his bad-boy image.

McQueen wore his counterculturalism loudly on his sleeve. Often tediously. He wanted to be dark, dark, oh so dark. Great. I think it’s pratty, but there are millions of people who don’t, so good for him — good for them. And even if he was a prat, he was still an interesting and unusual prat, idiosyncratic and determined, slashing into fashion clichés and reforming them. And, as the current V&A exhibition should show, McQueen really did have imagination.

That McQueen flourished (creatively, financially) within the industry he attacked was a mark of genius. The skull-print scarves he introduced went from unsettling, to edgy, to cool, to popular, to populist. Imitations now sell on market stalls the world over. The skulls became the polka dots they had originally replaced. It takes vision to achieve this level of William Morris universality.

Even his ‘bumsters’ — his arse crack-revealing innovation — transformed the builder’s bum into Rococo décolleté. It spawned low-waisted trousers and a lot of visible thong-ing and, when thong met bumster, the ‘whale’s tail’.

McQueen’s vision was unique. He was the first to introduce Grand Guignol theatrics into fashion. John Galliano, preceding him chronologically at Givenchy, had comparable flair and showmanship, but his vision was more ethnographic, more all over the place, and less determinedly dark. Vivienne Westwood’s earlier punk had been more genuinely subversive, but, crucially, less haute couture.

McQueen claimed to have gone ‘straight from my mother’s womb on to the gay parade’. But the names he gave his collections — ‘Highland Rape’ (1995), ‘McQueen’s Theatre of Cruelty’ (1993) and ‘Jack the Ripper Stalks his Victims’ (1992) — were more hardcore cruise club than Gay Pride.

His infatuation with darkness was pretty adolescent. Perhaps he was himself — and perhaps that’s why he ended his life in a drink and drug torpor.

Some collections name their sources (‘The Birds’, ‘The Hunger’). Sometimes he only alluded to them. Once he played Mia Farrow’s humming lullaby from Rosemary’s Baby as models went from darkened catwalk — one dragging a golden, life-size skeleton behind her — to a spotlit merry-go- round, where they were joined by clowns in skull masks! Other times, with more rigour, he did pastiches, probably unintentionally. His 2004 show was a laboured reenactment of Sydney Pollack’s They Shoot Horses, Don’t They? What did McQueen want? This was a 20-minute show to sell clothes, not a study of Depression-era human exploitation and desperation.

And yet, for the industry this is exiting stuff. It may seem irritating, but at least it’s not the same 50 models walking past in the same 50 dresses. And sometimes, it must have been amazing, really. Shalom Harlow, on a revolving platform, being sprayed by robot paint guns (1999). A life-size hologram of Kate Moss, with hologram yards of rippling fabric (2006).

This V&A show is an expansion of the 2011 exhibition staged at the Met in New York, which consisted of five rooms with different themes, each with its own soundtrack and lighting. Entirely appropriately, we will be looking at the staging, not the design.

It looks better, clearer, less fatuous than some of the V&A’s previous curations. Visitors to its Versace exhibition, for example, had to go through a door that set off flashing lights and a ‘paparazzi’ soundtrack, so they would feel like a Versace-wearing star. In one room, the mannequins were lit by a single roving spotlight — so each piece could be seen for five seconds every two minutes. I want the designer to be creative, not the museum.

And McQueen was creative. He didn’t simply rely on technical wizardry. He once replaced the catwalk with a paddling pool, the light bouncing off the splashing water. Simple, logical, uncontrived, it was perfect. The hair in that 1996 show was a Hasidic riff: a crew cut with elbow-length sideburns; the make up a horizontal line of colour below the eyelid, fading as it went down. The totality was incredible.

But take away the water, then the wig, then the make-up, then the model — and the dress is really not so much to write home about. What is the customer buying? The dress in the shop? Yes. But she is also paying for the brand, for the image, for the dream — and these are all conjured up through the staging.

McQueen as ‘amazer’ succeeds best when it is the clothes, not their presentation, that astounds. It’s easier to be bowled over by incredible proportions — unwearable shoes and hair — than by skeletons or dying dancers. McQueen gives us this. The models in the Plato’s Atlantis collection, with their carapace dresses, moulded wings of hair rising in symmetrical crests above ears, tall shoes curved down like claws, looked inhuman.

Even better, though, is when McQueen was more down to earth. When he obtained a less alien beauty, but with more alien tools. In 2001 he showed a dress made of razorclam shells, perpendicular shards, regular and repetitive, cumulative and simple. No angst, just beauty.

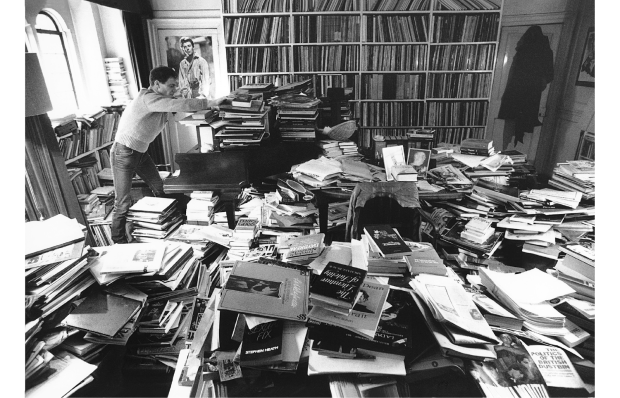

And yet, again, the show was set in a faux asylum (see image above), the models pretending madness, climaxing to glass walls crashing down to reveal a tableau of a fat lady on a chaise-longue, surrounded by dead and living moths and breathing through a gas mask… For one critic it was ‘Francis Bacon via Leigh Bowery and Lucien Freud’. For the fat lady herself, it was ‘William Blake-meets-Damien Hirst-meets-Joel-Peter Witkin-meets-Silence of the Lambs-meets-Slipknot.’ In the end, perhaps, it is the strength of McQueen that no one can say what his work is like — exactly because it is like nothing else. And this is why, despite the trying angst, it is good.

You can quibble meanly — or reasonably — but not deny that McQueen had a hand and vision all of his own. No one else’s collection could be inspired, simultaneously, by Queen Victoria and the tree in his back garden. His vision may have been melodramatic, but it was consistent, varied, unignorable, undeniable and unforgettable.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Alexander McQueen: Savage Beauty’ is at the V&A until 2 August.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in