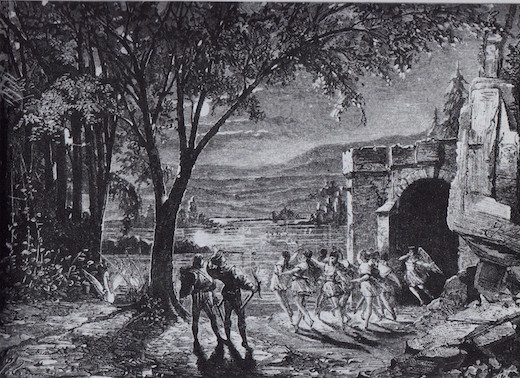

It is the end of an era — the Royal Ballet’s extravagant Fabergé-egg Swan Lake production by Anthony Dowell is on its last legs. When this 28-year-old production finishes the current run on 9 April, that will be it for one of the most controversial classical productions of the past half-century. It’s the one set in Romanov Russia, festooned with ribbons and golden squiggles, with swans in champagne ball-gowns rather than pristine white feathers. Hallucinatory, glamorous and opulently symbolist? Or hectic, fussy and tatty? Adjectives divide between the adoring and the withering for Yolanda Sonnabend’s Gustave Moreau-esque designs and for Dowell’s hyperactive staging.

Last month marked 120 years exactly since the première of Swan Lake, as we know it, with the iconic sweepings of white swans created by Lev Ivanov, and the stomping vivacity of the court scenes by Marius Petipa, but everywhere you see a different production. English National Ballet’s is a quite distinct experience from the Royal Ballet’s; the Bolshoi’s is clammy, the Mariinsky’s is cool yet oddly cheerful. They have happy endings, sad endings, this music, or that music, this dancing, or that dancing. You hear Russians today swear that the west stole their ballet. You hear British fans retort that the Soviets murdered Swan Lake.

I understand the blinkered, possessive love: to me Swan Lake is the great enigma of ballet theatre; its music has Wagnerian emotion and spiritual power; the swans are extraordinarily potent metaphors; the theme of a man betraying himself is painful — it hits you personally. But I cannot really say that Swan Lake exists as a real text; it’s an act of private imagination.

It may amaze people who go to opera and theatre, but classical ballet has been lamentably cavalier with its own textual basis. All the 19th-century ballets, as we think we know them, are palimpsests of staging fashions and evolving dance skills, and Swan Lake is an extreme example of it. Ballet stubbornly remained an oral tradition, despite sporadic attempts to launch notation systems for dancers to use as universally as musicians use scores.

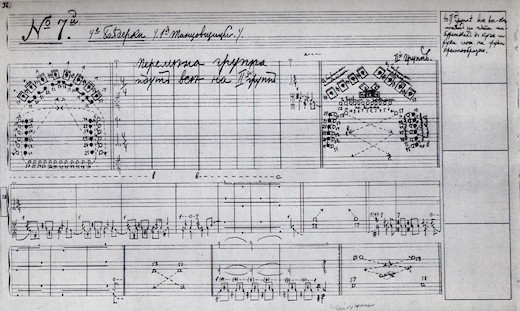

But then came the invention by a young Russian anatomist, Vladimir Stepanov, at the end of the 19th century of a sophisticated system to record movement to music itself. A project to notate the entire repertoire of the Imperial Ballet, the golden age of classical ballet, was launched. By a quirk of history, it is Britain that acquired this golden record, and our audiences have inherited its priceless contents.

When the former balletmaster of the Imperial Ballet, Nicholas Sergeyev, fled the Revolution with the entire record of notations of the Imperial Ballet’s repertoire, terrified that they would be destroyed, he settled in London. By this illicit act he saved classical ballet itself, and enabled the pre-eminence of the British choreographic tradition. And so a Swan Lake in Birmingham could be more closely related to those of the golden age of Russian ballet than any in St Petersburg now, where Soviet productions are still extant.

The Soviets had made major adjustments to classics to replace Tsarist or religious symbolism with an athletic modern aesthetic in tune with the proletarian utopia. So in Russia an alternative, revisionary tradition took hold, where Swan Lake now ended happily, and left the people untroubled.

Greatest criticism of Dowell’s production has been launched at the laddish prince and busy maypole, and — most keenly resented by many balletomanes — the loss of poetic sequences of dance known and loved in earlier productions. I’ve often wondered whether I misunderstood why Dowell made his choices, and what issues would face whichever benighted soul has to face the ire of the public when they replace it. This was the last time to find out.

What the true Swan Lake is has always been controversial, because of the butchery done to Tchaikovsky’s score by the choreographers who created those immortal images. Many define the ballet by its 1877 score, which was saddled with an unsatisfactory staging. Others say it is the great choreographic version of 1895 that rules, even with its musical adaptation — some of the most familiar dance moments are set to music by Riccardo Drigo, not Tchaikovsky.

Purists among his haters will be surprised to hear that Dowell felt he was returning a much-revarnished classic to its source. His production is far closer to the 1895 première than to the memorable Royal Ballet production he danced, immortalised on film with him and Natalia Makarova in 1980, a version considered by Western ballet critics to show the Royal Ballet’s highest classical style (pictured above). In fact, this was a modern 1960s assemblage, mostly by Frederick Ashton, which, poetically and dramatically, strayed from the original.

For one thing it preferred Tchaikovsky’s 1877 music to the later performing version of 1895. For another, Prince Siegfried’s role was rather skimpy in 1895, and Rudolf Nureyev, the newly defected superstar from the Kirov, was having none of this. He inserted a great yearning Russian-souled soliloquy that skews the story in a sophisticated new direction.

Many watchers feel that this solo must be integral. Dowell loved dancing it. He says it suited his adagio style. But he told me he found that the original 1895 scenario made sense in a different way. The prince is, as he puts it, less Hamlet than Prince Harry, a party-loving youth, which makes his life-changing encounter with the swans all the more powerful.

It’s paradoxical now that many commentators see Ashton’s 1960s additions as more authentic than original elements that Dowell took great pains to restore.

Scottish Ballet announced last week that it’s commissioned a new Swan Lake next year from the young choreographer David Dawson; it can be expected to be very much a new version. The Matthew Bourne modern version has had an explosive effect on preconceptions about acceptable classical rewrites — even in Russia it’s been acclaimed for its authentic use of the music and its true understanding of the dramatic imagery.

But the Royal Ballet is a classical ballet company with a traditionalist tradition and a quite young generation of choreographers who — as Dowell pointed out — like to browse YouTube’s vast world of ballet clips, rather than imbibing house traditions shaped by a master choreographer. And Swan Lake is the Everest of the public’s dreams — any new choreographer or stager knows they will have to tread softly. The Royal Opera House says it cannot say when the next Covent Garden production will be launched.

It’s intriguing that the old Stepanov notations that were saved by Brits are gradually yielding fruit, as they are deciphered and reconstructed. There are the early stirrings of a new ‘authentic’ movement in ballet, to separate out the different strands of period style from the current mishmash, with the appearance of several classical reconstructions in both America and Russia. It’s hard to say how far it will go. The Mariinsky briefly flirted with a wholesale return to the 1890s, with stupendous recreations from the notations of La Bayadère and the original 1890 The Sleeping Beauty, which showed how pricelessly faithful the Royal Ballet stagings have been to the choreographic source, thanks to that fugitive balletmaster from Russia.

After all the fuss and pother around Dowell’s production, it will be a historic irony if it becomes the significant source for the future of a text in which to find that first, overwhelming 1895 staging.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in