For his holiday reading in the summer of 1835, the literary and political journalist John Wilson Croker packed the printed lists of those condemned to death during the Reign of Terror in revolutionary France. The several thousand guillotined in Paris after the establishment of the Revolutionary Tribunal (10 March 1793) and before the fall of Maximilien Robespierre (27 July 1794), were accused of crimes ranging from hoarding provisions or conspiring against the republic to sawing down a tree of liberty or declaring ‘A fig for the nation!’ In horrified disbelief Croker asked the question that has never gone away: how could this have happened? How could the progressive revolutionary optimism of 1789 have turned in just five years to summary arrests and executions?

Two new books shed light on this murky topic. In The Coming of the Terror in the French Revolution, Timothy Tackett, Professor of History at the University of California, analyses the mentalité of those who became ‘terrorists’ in 18th-century France. In a previous book, Becoming a Revolutionary (1997), Tackett wrote about the mentalité of those who took responsibility for designing a new French constitution in 1789. In extending his work into the period of the Terror, Tackett engages directly with Croker’s question: how did the revolutionaries and their revolution go so wrong?

Fear, unsurprisingly, turns out to be foundational for the perpetrators of terror: ‘Terrorists themselves felt terrorised.’ Fear, Tackett argues, was a central element in revolutionary violence: fear of invasion, chaos, anarchy, conspiracy and vengeance. By 1793, such fears were rational. France was embroiled in both a civil and international war. There had been no stable government or system of public finance since before 1789.

In his reconstruction of both the emotional and rational repertoires of revolutionary behaviour, Tackett relies on contemporary letters and diaries. These sources, he suggests, are less mediated than memoirs or retrospective histories. He draws on letters from a variety of people and milieus: men and women, commoners and nobles, Parisians and provincials. He refers to the letter-writers as ‘witnesses’.

Four letter-writers play pivotal parts: Adrien-Joseph Colson, an estate agent; Nicolas Ruault, a publisher; Rosalie Jullien, the wife of a delegate to the National Convention, elected after the collapse of the monarchy in 1792 to design a republican constitution; and Gilbert Romme, a mathematics teacher and politician who committed suicide in prison in 1795.

Romme was an early advocate of terror. In October 1789, after the fall of the Bastille and the march on Versailles, he predicted that if the whole population of France were to be converted to the blessings of the revolution, ‘reason will perhaps need to be accompanied by terror’.

As the revolution continued, uncertainty, anxiety, nightmares, rumours and denunciations multiplied. Even before the Revolutionary Tribunal and other institutions of the Terror of 1793–4 were established, there was an ‘everyday terror’, where everyone spied on everyone else in ‘a vicious circle of grassroots suspicion’. Tackett’s claim is that this state of affairs was integral to the process of revolution: it was not the product of ideology or circumstance, but a necessary part of the process of demolishing the old regime and establishing the new.

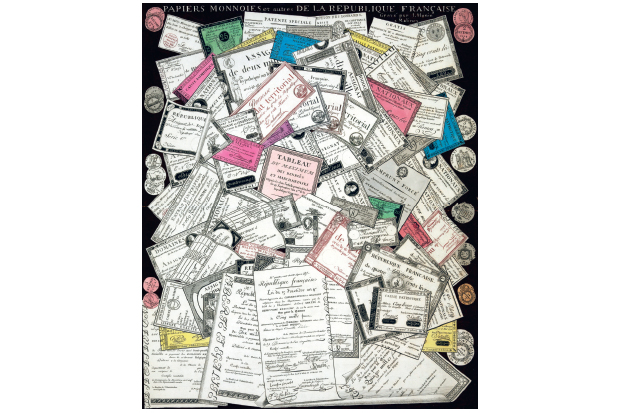

In Stuff and Money in the Time of the French Revolution, Rebecca Spang, an associate professor at Indiana University, brings the fear intrinsic to revolution into sharper focus by concentrating on the scarcity of coin and proliferation of a paper currency. Instead of considering the use of violence during the revolution, she concentrates on the regulation of money. She argues that historians have previously looked through money but not at it. Since money is a convention based on trust and reasonable expectation, examining its function exposes the challenges at the heart of regime change.

Beginning with an epigraph from John Maynard Keynes, ‘Money in its significant attributes is, above all, a subtle device for linking the present to the future’, Spang argues that in taking responsibility for the old regime’s debt and simultaneously cancelling the old system of taxation, the revolutionaries in 1789 were literally indebted to the past. For all their rhetoric of rupture and regeneration, they were men confronted with debts, debris, memories and tax arrears.

The old regime lived on credit. Cash in the form of gold, silver, copper and brass coins had its uses but was not the only, or even most common, way of making a purchase. In 1769, for example, Madame La Roche went 16 months before paying a caterer for the regular meals that he had provided for her parrot. The people who most needed coin were the poor, who could not get credit. When there was a scarcity of small change there was the risk of revolt, because without coin the poor could not buy bread.

After 1789 people hoarded money. There was a shortage of coin and confiance or trust. It was in these circumstances that the National Assembly decided to issue the assignats, a paper currency secured on the newly appropriated church lands. The publisher Ruault declared:

These assignats will be the best money in Europe… we can pay for everything without having to tax the people. The French people are really going to be franc [debt-free].

The assignats never circulated as freely as coins. Counterfeiting was a problem from the start: no one could be sure that payment in assignats would be accepted when the provenance of the paper bills could not be trusted. A further problem was the National Assembly’s refusal to fix the exchange rate between coin and paper. Favouring free trade in money as in grain, they pushed deregulation to an extreme. The result was chaos.

In this context, where the French state and economy were simultaneously failing, the Terror was an attempt to assert control. The establishment of the Revolutionary Tribunal coincided with centralisation of the assignats. While the public prosecutor Fouquier-Tinville presided over who would live or die, François ‘Publicola’ Deperey became the French Republic’s verifier general of assignats: the one man in France whose pronouncements on counterfeits were final.

In emphasising weakness and uncertainty instead of fanatical strength as the driving force behind the Terror, both Tackett and Spang contribute to an important realignment in the study of French history. What are the lessons of the Terror for today? Parallels between ideological fanatics prepared to resort to violence in realising a distinctive vision of the good life are less informative than a patient appreciation of how and why the first French Republic failed.

By 1795 Ruault, who had once been Voltaire’s editor and had welcomed the revolution and the assignats, could only survive by selling off his personal possessions week by week. He declared himself ‘an atheist in matters of revolution’, ready to leave Paris and live somewhere ‘as quiet as a country rabbit’.

Ruault’s revolutionary fatigue was shared by hundreds of thousands, from the poorest to the most powerful: the struggle to found a modern state and economy amongst the detritus of the old regime proved much more difficult and exhausting than the optimists of 1789 had supposed.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

'The Coming of the Terror in the French Revolution', £22.50 and 'Stuff and Money in the Time of the French Revolution', £22.50 are available from the Spectator Bookshop Tel: 08430 600033. Ruth Scurr is the author of Fatal Purity: Robespierre and the French Revolution. Her life of John Aubrey will be published next month.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in