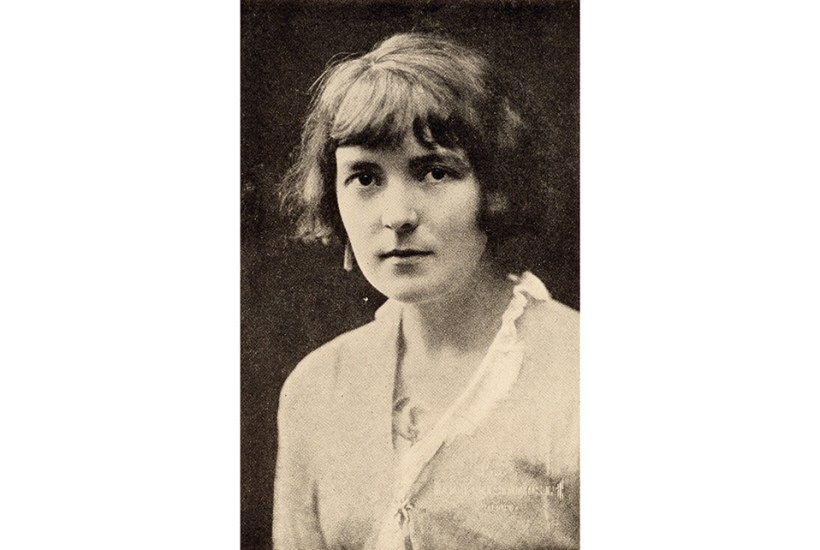

A hundred years ago, in a former Carmelite monastery 60 kilometres south of Paris, Katherine Mansfield ran up a flight of stairs to her bedroom and died of a haemorrhage. She was 34 years old. She had known for five years that she had tuberculosis. After joining the spiritualist therapeutic community at Fontainebleau-Avon in October 1922, under the guidance of the Russian guru George Gurdjieff, she had been careful to avoid stairs, or only to take them very slowly. But on the 9 January 1923, her husband, the writer and editor John Middleton Murry, came to visit and they enjoyed an evening watching other members of the commune dancing. In a fit of high spirits, or recklessness, forgetful of the painful constraints on her body, Mansfield took off for the last time upstairs and never came down.

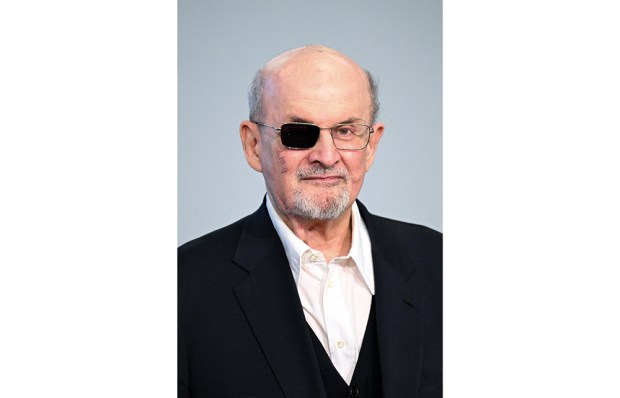

Claire Harman, a distinguished literary biographer, has written a wonderful book to mark the centenary of Mansfield’s death. Determined to consider the work and life in tandem, Harman chooses ten of Mansfield’s short stories, some renowned, some obscure, and discusses them in connection with her life.

Mansfield pioneered fragmented narratives full of the ‘so-called small things’ and ‘the detail of life, the life of life’. Harman argues that in the aftermath of her death, Mansfield’s ‘irregular and short life, devoted as it was to an irregular short form, didn’t fit at all well with the dominant idea of pantheon literature, on a large scale, with heroic resonances’. She has sometimes been overlooked or condescended to (Wyndham Lewis dismissed her as a ‘mag.-story writer’, D.H. Lawrence predicted she would ‘fade’, and T.S. Eliot thought her reputation ‘inflated’), but in our age of pandemics, loneliness and an overwhelming number of texts online, Harman suggests, appreciation of short stories – which ask ‘the biggest questions in the smallest spaces’ – is burgeoning. It is time to fully appreciate Mansfield as the link between Anton Chekhov and Alice Munro in the gallery of greatest practitioners of the genre.

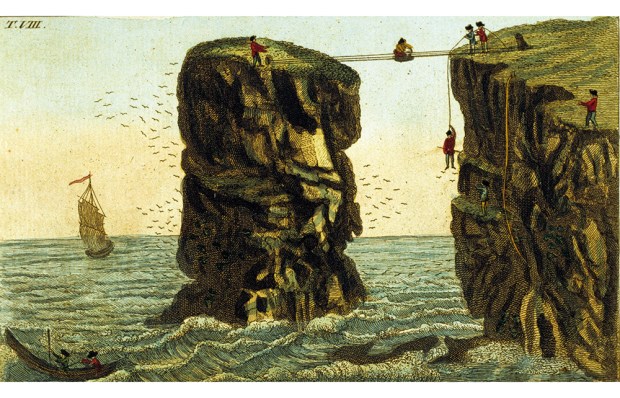

When, aged 19 and known as Kathleen Mansfield Beauchamp, she set sail for London from New Zealand on the SS Papanui in August 1908, she already had innovative manuscripts in her luggage. One of them, a short story called ‘The Tiredness of Rosabel’, was inspired by an earlier trip to London that she had made with her wealthy family in 1903, before attending a girls’ school in Harley Street. Rosabel works in a milliner’s shop and lives in a cold, fourth-floor rented room in Westbourne Grove. As she walks home exhausted from the bus stop one evening, ‘she thought of those four flights of stairs. Oh, why four flights!… Every house ought to have a lift, something simple and inexpensive, or else an electric staircase like the one at Earls Court.’

Because there was no escalator at Earls Court station until 1911, previous commentators have assumed the date of 1908 on Mansfield’s manuscript was a mistake, and the story, which was not published until 1924, after her death, could not have been written by a teenager in Wellington. Harman points out that there was something called an ‘electric staircase’ at Earls Court Exhibition Hall from 1901, which Mansfield could easily have seen and used during her school days in London. Harman’s scholarship is not the showy look-at-me variety; it is matter-of-fact, and always at the service of the texts.

Mansfield’s first book, In a German Pension (1911), was what first attracted Murry to her, because it ‘seemed to express, with a power I envied, my own revulsion from life’. By the time they met, Mansfield and Murry had both contracted gonorrhoea, and Katherine had been married for a day to a singing teacher while pregnant by another man. She lost the baby in a spa in Bavaria where she wrote the stories for her first collection. One of them, ‘The Child-Who-Was-Tired’, was a version of Chekhov’s story ‘Sleepy-head’, about an oppressed, young, sleep-deprived servant girl who thinks the only way she can rest is by killing the baby she is looking after. In 1951, a letter in the Times Literary Supplement accused Mansfield of plagiarism, and suggested her unwillingness to republish In a German Pension was an attempt to conceal her theft from Chekhov.

Harman has a more sophisticated and artistically informed interpretation. She understands that Mansfield was learning from Chekhov, while composing a story that was emphatically her own. ‘We all as writers, to a certain extent, absorb each other when we love,’ Mansfield declared. ‘Anatole France would say we eat each other, but perhaps nourish is the better word.’ From Chekhov she learnt to eavesdrop on her characters, to watch rather than moralise. She often dreamed of him:

Ach, Tchekov! Why are you dead! Why can’t I talk to you – in a big, darkish room – at late evening – where the light is green from the waving trees outside.

Harman’s clever insistence on placing the life and work side by side allows her to give brief but powerful accounts of Mansfield’s relations with other writers, especially Virginia Woolf. Woolf wrote nastily that Mansfield had been going ‘every sort of hog since she was 17’ and stank like a ‘civet cat that had taken to street walking’. Harman thinks this might have been because Mansfield wore musky perfumes such as Peau d’Espagne, which appears in her vignette ‘Summer in Winter’. But cattiness between the Bloomsberries and a ‘little colonial’ does not interest Harman as much as the deep literary exchange between them. She quotes a letter Mansfield wrote to Ottoline Morrell about Garsington, wondering ‘who is going to write about that flower garden’. She imagined several pairs of people walking and talking and their ‘conversation set to flowers’. There is a lost letter from Mansfield to Woolf along the same lines that probably inspired Woolf to write her story ‘Kew Gardens’, in a completely different register from her early novels. ‘But if Katherine was put out by the rapid take-up of her idea,’ Harman writes, ‘she didn’t show it, writing in encouraging and appreciative tones to Virginia that “your Flower Bed is very good”.’

Harman’s title, All Sorts of Lives, reflects the imaginative energy that drove Mansfield’s work to the point where, frightened she might die before enough of it was finished, she once stopped on the stairs to write down a sentence that was in her head. To Murry she observed:

What a QUEER business writing is. I don’t believe other people are ever as foolishly excited as I am while I’m working … I’ve been this man, been this woman, I’ve stood for hours on the Auckland Wharf. I’ve been out in the stream waiting to be berthed. I’ve been a seagull hovering at the stern and a hotel porter whistling through his teeth. It isn’t as though one sits and watches the spectacle. That would be thrilling enough, God knows. But one IS the spectacle for the time.

Just one life, Mansfield knew, ‘is so very small’, but fiction – both reading and writing it – offers the opportunity to experience all sorts of lives beside and beyond our own. Harman notes that Alice Munro ‘who has in our own century brought the [short story] form to a point of perfection that Mansfield would have marvelled at, has said she “just clung” to the older writer’s example’, as Mansfield in her turn had clung to Chekhov’s. Mansfield described herself during one episode of painful illness as sitting down at the table, ‘leaning on anything I can find – leaning on my pen most of all & though I do write – it is only a matter of “will” – to break through’.

Intensely self-critical of all her achievements, even of the brilliant ‘Bliss’ and ‘The Garden Party’, she died leaving instructions for Murry to destroy her unfinished manuscripts. He disregarded her wishes and published everything that he could find – drafts, poems, journals and letters. D.H. Lawrence wrote: ‘I think it’s a downright cheek to ask the public to buy that wastepaper basket.’ But Harman’s careful sifting of the evidence proves him wrong. In her book we see Mansfield vividly, pushing her powerful pen across the page, closing the space between herself and her readers, whom she meets, as Harman concludes, ‘on common ground, and stretches out a hand’. ‘I mean to make life wonderful if I can,’ Mansfield wrote. ‘That’s what writing means to me – to enrich – to give.’

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in