A life-long supporter of the ALP, never in my 66 years had Labor’s primary vote sunk to the level it did at the 2013 election. And my party’s woeful performance in the recent Western Australian Senate election rerun adds underlining and an exclamation mark. So I ask myself: where is my party heading on policies for social and economic reform? For you cannot separate social from economic policy. My message is for Labor, but it also has resonance for the Coalition.

Labor’s first policy initiative, as outgoing WA Labor senator Mark Bishop made clear this week, should have been to drop its support for the carbon tax. Surely it would have made electoral common sense for Bill Shorten to have done so, saying we have heard the voice of the Australian people. After all, Tony Abbott received the clearest and most emphatic of mandates for his policy (if that wasn’t one, we should stop talking about mandates altogether). And what will happen down the track if the boot is on the other foot?

Arguably more important, by not doing so Labor risks being seen as still too close to the Greens and their ideology, notwithstanding saying there will be no more alliances with them.

Anyway, what other policy priorities might Labor now embrace? Three spring to mind.

First, as Martin Ferguson and others have argued, Labor must not resile from the Hawke government’s pro-market economic reforms of floating the dollar, tariff reductions, privatisation and deregulation of wage-fixing, as these policies were the drivers for the two decades of economic growth that convinced the Australian people it was best able to manage the economic challenges of the 1980s.

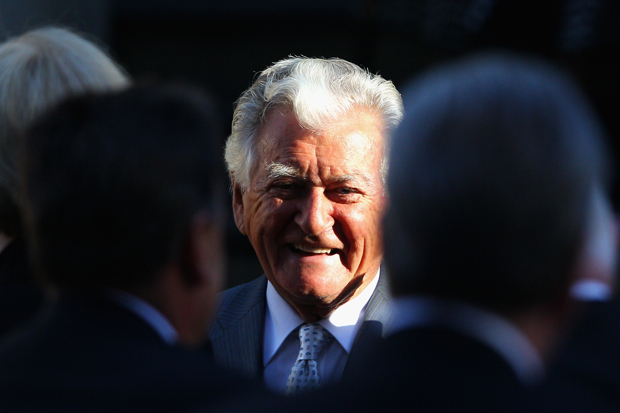

Labor’s working-class supporters did not desert the Hawke government in droves when it took these measures, although the high mortgage rates and tariff reductions tested them. There were no Howard battlers when Bob Hawke was Labor leader.

In his Monthly articles, Kevin Rudd fretted and wailed about government offsetting the inevitable inequities of markets by its commitment to fairness for all. He initiated huge expenditures on Green strategies and the National Broadband Network (for which no cost-benefit was undertaken) cap and trade, all of which were ostensibly designed to correct market failures.

Rudd announced the mining tax without consultation, while Wayne Swan assumed responsibility for the class warfare rhetoric, which did not resonate with the working class; nor does the politics of envy. As a senior minister in Rudd’s government, Julia Gillard was responsible for the mismanaged Building the Education Revolution programmes and handing control of workplace regulation to the unions. As Prime Minister, her legislative agenda included a new bureaucracy for National Preventative Health, bureaucratic controls over the ozone layer and legislation to ensure Australia’s consistency with the many and varied human rights conventions churned out by international agencies. Labor should reject the Rudd and Gillard governments’ backsliding on economic reform.

Second, Labor has been the party of social reform in Australia, with Medibank/Medicare one of its greatest achievements (and it should not be forgotten that John Howard fought Medicare to the last, until finally overwhelmed by public opinion). Labor should continue this tradition, but only when it’s economically responsible to do so.

Disability insurance is a worthy objective, with widespread community support for the genuinely disabled and their carers gaining better access to assistance from government — all the more reason for not introducing a scheme lacking in detail as to how it is to be administered (in particular, eligibility requirements and size of the bureaucracy) and only funded with $200 million for the first year out of an estimated cost of $14.5 billion a year (marginally less costly than Medicare) once the roll-out is complete in 2018-2019. Gillard and Rudd will no doubt claim the National Disability Insurance Scheme as their legacy, notwithstanding they won’t have delivered it.

Third, Labor should promise to put an end to middle-class welfare. Such a policy would also differentiate it from Coalition governments who are addicted to such policies. In opposition, Tony Abbott advocated an expansion in middle-class welfare; his paid parental leave scheme saw him recommit to it once in office. He is following in the footsteps of his mentor, John Howard, who introduced the universal 30 per cent private health insurance rebate and other such gems. Howard claims the term middle-class welfare is ‘dishonest’, as these measures are not income support but designed to change people’s behaviour, in other words social engineering. Abbott’s paid parental leave scheme is unlikely to change the behaviour of a person earning $150,000 a year. It is inequitable, and it is an entitlement that, at an estimated cost of $5.5 billion a year, will be a massive hit on a budget the government (and most business economists) says needs to be reined in.

In his paper delivered to London’s Institute of Economic Affairs in April 2012, Joe Hockey enthusiastically argued for fiscal discipline: ‘The end to the age of entitlement.’ Obviously, the government he is the Treasurer of will not be practising what he preached.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Michael Thompson is author of Labor Without Class: The Gentrification of the ALP (1999).

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in