When I visited the Richard Deacon exhibition at Tate Millbank, there were quite a lot of single men of a certain age studying the exhibits with rapt attention — some even making notes. (I realise I’ve just described myself…) This is perhaps because the show is all about the glories of construction, and reminiscent of hobbies on an industrial scale. The exhibits are made of bent wood, looping metal, other materials cut or sewn or carved, exoskeletons of imaginary, or rather invented, things. Much of the early work in this fascinating survey is linear, the structures resolutely open, but the emphasis gradually becomes more volumetric and involved with three-dimensional plasticity. Richard Deacon (born 1949) is an object-maker of intriguing presence and diversity.

This survey is chronological rather than thematic and begins in the first room with three sculptures on the floor and five large drawings on the walls. The sculptures are all untitled and recall a seashell, the interior jointing for a plinth, and origami in fibreglass treated to look like galvanised steel. The drawings hold the attention, particularly in the way a final design seems to crystallise out of a matrix of linear possibilities. But I do take exception to the style of labelling exhibits now so prevalent in museums: I think the titles, dates and media should be presented beside the object in question, and not fashionably grouped near the door to ensure some sort of specious ‘wall purity’. And I think most visitors would agree with this, though their wishes are often the last to be considered.

In the second room are three open structures, two made of laminated wood, one of galvanised steel with wood and canvas, which are springing, optimistic yet oddly tranquil forms, resolved rather than tentacular. The third room contains three large metal floor pieces and a single biomorphic wall sculpture. Here the linear blossoms into the massy. The centrepiece is the writhing and reclining ‘Mammoth’, like riveted ventilation ducts. ‘Struck Dumb’ is a solid form securely soldered, excluding us but also imprisoning whatever is inside it. There’s a change of pace in Room 4, which is devoted to small, unexpected floor pieces, presented on a biscuit-thin plinth like a Carl André sculpture. They all come from the 1984 ‘Art for Other People’ series, and make inventive use of suede and brass, white earthenware, marble and leather, nylon net, and so on.

Room 5 is devoted to a further trio: a little green ceramic thing called ‘Lotus’, the attractive terracotta ‘Waiting for the Rain’, like a large handful of squeezed clay, and the massive wooden coiling of ‘After’ with its meshed stainless-steel backbone, resembling a dividing fence or interior portcullis. This sculpture is very contained, like an endless spirograph doodle in three dimensions or a worm trying to escape itself; also a symbol of infinity. The last room, by contrast with the previous galleries, seems rather crowded: better to have reduced the exhibits to ‘Out of Order’, a contorted construction of strapped and steamed oak planks, and a couple of wall sculptures. ‘Out of Order’ is a disquieting work to end on: the most uncomfortable piece in the show, it resembles enormous shavings from a giant woodworking plane. It’s a very anxious object, without any sense of rest or equilibrium.

In keeping with what is becoming accepted practice, the publication accompanying the exhibition is a monograph on the artist rather than a catalogue, thus augmenting the book’s shelf life by not tying it too closely to a single time-sensitive event. However, many of the works discussed are in the exhibition, so anyone wishing to learn more about the artist will gain a lot from this handsomely presented paperback (price £16.99). The Richard Hamilton catalogue, on the other hand, is a doorstopper of 350 large pages (£29.99 in paperback), which poses questions like: ‘How would Hamilton possibly have distinguished his citational iconography from that of his American colleagues?’ (p.95) I’m afraid I had neither the desire nor the energy to discover the answer to that one.

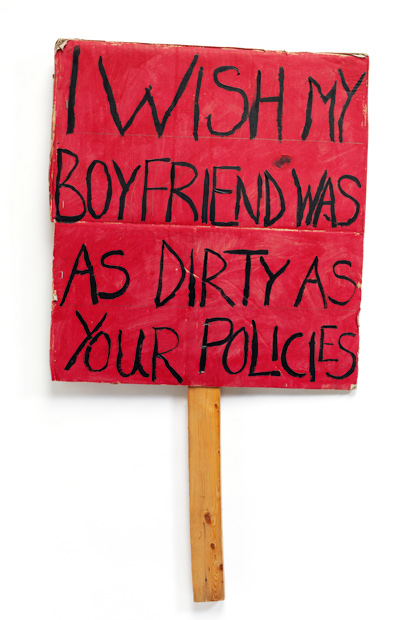

It’s a sad fact, but I feel I’ve seen too many Richard Hamilton exhibitions. I used to think he was an interesting artist (particularly the early work) but now I view him more as a cultural phenomenon. He gives good copy to those art writers who don’t particularly relish the materiality of painting and sculpture but love ideas. And I recognise that he was a formative influence on younger generations of artists and students (as he probably still is), and that his latest work, as it appeared hot from the studio, had a deep and in some cases lasting impact. I’ve lived through some of it myself. I certainly remember seeing the Margaret Thatcher film installation of ‘Treatment Room’ when it was first shown at Liberty’s in February 1984. Then it was striking and perhaps provocative; now it looks like most political art — a dated document.

Perhaps this is the trouble with Hamilton’s work: it is so much of its time that it only rarely moves into that transcendent timeless category of great art. There are one or two pieces that do approach this exalted state: ‘Portrait of Hugh Gaitskell as a Famous Monster of Filmland’ (1964) and perhaps ‘The Citizen’ (1982–3), but so much of the rest is aesthetic or intellectual manoeuvring. Even those early paintings I was looking forward to seeing again — the ‘Hommage à Chrysler Corp’ (1957) period — now look thin and insubstantial, dandyish explorations of post-Cubist stylisation. Some of the freshest exhibits in the early part of the Tate’s vast show are the series of 17 ‘Reaper’ etchings from 1949, and even those begin to edge a bit too close to one of Hamilton’s greatest idées fixes, Marcel Duchamp. For the rest, the obsessions with excrement, porn and dickering about with the Old Masters are just rather irritating mannerisms. Technically, the later work exhibits a determined renunciation of the painterly touch and flaunts a catastrophic over-reliance on photography and digital printing.

Some of the most interesting exhibits appear in the very first rooms of the show, the subject ‘Growth and Form’, a re-creation of a 1951 exhibition Hamilton organised for the ICA. This is far more impressive than the rather sad remnants of the truly ground-breaking This Is Tomorrow show, originally mounted at the Whitechapel in 1956, now gathered in Room 4. The destructive passing of time is a major if unspoken theme throughout the exhibition. As art it doesn’t add up to much, as ideas, rather more. After this exhaustive show (his third Tate retrospective), Richard Hamilton (1922–2011) should be confined to the history books and given a well-earned rest from museums.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in