Titles can be misleading, and in case you have visions of microwave ovens running amok or washing machines crunching up the parquet, be reassured — or disappointed. Disobedient Objects, the new free display in the V&A’s Porter Gallery, is about objects as tools of social change. It’s a highly politicised exhibition and contains a great deal of fascinating material, from films to how-to guides (not quite ‘how to make a bomb’, but nearly). The gallery was packed when I went along. An admission charge might have made a difference. However, this is the kind of exhibition that should be free in a democratic country — if only to remind as many of us as possible what repressive regimes elsewhere impose on their luckless populations.

The exhibition installation is a very vertical one — appropriate in this tall space — built around closely grouped polished aluminium scaffolding rods stretching from floor to ceiling, inevitably suggesting the bars of a cage or prison. The rods divide the space and provide a structure within which to place exhibits or from which to hang them. Display cases are made from heavily textured fibreboard, and these deliberately rough-and-ready materials give a sense of unpolished immediacy to the proceedings that matches the mood of the content. It’s a small, confined space despite its height, and noisy with music and speeches. There’s a discernible buzz here despite the historical context: the period surveyed ranges from the 1970s to now. The issues are real ones, the grievances seem legitimate and the action taken (by way of the objects on display) still speaks to us today.

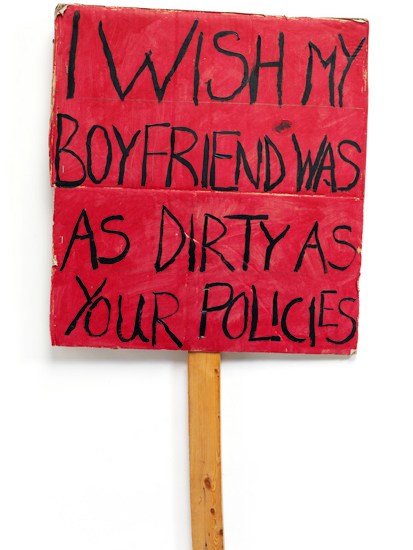

Some of the objects have the inventiveness of desperation (a gas mask made from a plastic bottle, for instance), others the greater deliberation of agitprop — such as the three large and expressive papier-mâché puppets made in 1991 by the American Bread and Puppet Theater. Then there’s the ‘Squatters Handbook’ (1979), priced 30p, produced by the Advisory Service for Squatters, and now loaned to the exhibition by the London Borough of Lambeth (though not the People’s Republic of Islington). There are tokens of solidarity such as the red square and the red feather (in support of Canadian student protests against rising tuition fees), the Trini dolls from Mexico (representations of the Zapatista leader), or the pink triangles of the gay community calling for Stateside unity. There’s a whole cabinet of badges against apartheid, and a rather arresting chrome-plated steel pendant bearing the legend ‘Fuck the Law’, made in a Louisiana penitentiary. There’s lots of documentary material (film footage, taped interviews) and some wonderful appliqué banners. This is a different kind of popular art and makes a provocative coda to the Tate’s British Folk Art exhibition.

The objects range from the handmade to the technological and sophisticated. In the latter bracket are two of the most mind-catching exhibits: the Flone (made in Spain, 2013), which is a home-made flying machine, a drone that carries a mobile phone to film police at demonstrations, or carry small objects about; and the robotic graffiti writer, which sprays slogans by remote control. For the rest there are embroidered hankies (by a mother whose son was abducted), a Palestinian slingshot made from the tongue of a shoe and a rice-bag T-shirt. There’s also the Bike Bloc, the unholy union of discarded bicycles and audio equipment welded together during the 2009 Reclaim Power protests in Copenhagen, and the lock-on device, which enables protesters to be (relatively) securely attached to a fence or similar. Although this exhibition might seem to be a beginner’s academy for terrorism, the only bomb they tell you how to make is a pamphlet bomb, as used in South Africa from 1969 to distribute leaflets against apartheid. These apparently harmed no one. Interestingly, the devices were invented and tested in Britain by ANC exiles.

One of the most impressive exhibits is ‘The Tiki Love Truck’, adorned with orange and blue mosaic and surmounted by the death mask of John Joe ‘Ash’ Amador, who was sentenced to death and executed in Texas in 2007. Although the truck was intended primarily as a statement about the death penalty, it is impossible to ignore its aesthetic content, which has no doubt immeasurably contributed to its effect at rallies, parades and festivals. It has been beautifully done, with much love and care, and no little skill: certainly here art has allied with protest. A more accurate title for the show might be ‘Obedient Objects: Disobedient People’, but then such an undemocratic implication might upset people and we wouldn’t want to offend anyone, would we?

If you’re anywhere near the east of England, there are other reasons to go to Snape Maltings besides music. There are shops and food markets, places to eat and drink, and there’s the Lettering Arts Centre, which currently houses an entertaining and instructive exhibition of work by Leslie MacDonald Gill (1884–1947). Max, as he was known, was the younger brother of the more famous Eric Gill (there’s definitely a book to be written about younger brothers of artists: John Nash, Gilbert Spencer, Laurence Whistler and now Max Gill). Eric seems to have disapproved of his sibling’s levity and designs, and this may have contributed to Max’s eclipse since his death. Little remains of the high reputation he won during his life, and it’s definitely time for a reappraisal of his achievements.

Max trained first as an architect in Bognor Regis, before moving to London as assistant to the firm of Nicholson & Corlette. He soon developed a talent for the decoration of churches, and kept up an architectural practice throughout his life, specialising in domestic dwellings. But he was to become best known as a designer, and both Max and Eric studied lettering under the great Edward Johnston, widely considered to be the father of modern calligraphy. Although Max was strongly influenced by the Arts and Crafts tradition, he was enough of his own man to originate an intensely personal style of lettering and design. Unlike Eric, he was not much interested in the human figure, preferring geography and buildings, and he soon became known for his graphic illustration, tiles and heraldry.

In 1913, Max was commissioned to design a decorative poster for the London Underground, and came up with a humorous and memorable solution: ‘The Wonderground Map of London Town’. This was displayed in Tube stations all over the capital, but a folded version was also available for sale, which proved immensely popular. Indeed it is the pictorial maps and posters that provide much of the convincing weight of this show: substantial things that are both works of succinct design (and information conveyance) as well as sources of aesthetic pleasure and amusement. An effective sequel was Max’s map of London theatreland; others followed, with the Empire Marketing Board, the Post Office and Cable & Wireless joining the list of Max’s clients.

The other significant aspect of his work was as lettering expert for the Imperial War Graves Commission. It is Max’s lettering and designs for the regimental badges that distinguish the simple white military headstones that record the fallen of two world wars, some of them movingly ‘Known unto God’, as the sample headstone in the gallery proclaims. There are lots of smaller exhibits, from postage stamps to book jackets and jam labels, and lettering of all kinds. There is a remarkable elegance and flow to Max’s work, which may ironically have been another contributing factor to his life’s achievement not being taken seriously. But the range and impressiveness of this exhibition should help to change that.

The centre is closed midweek, but open Mondays, Fridays, Saturdays and Sundays from 11 a.m. to 5 p.m. The shop carries a whole range of publications and desirable objects, whether maps, prints, ceramics, calligraphy or carvings. You can also become a friend of The Lettering and Commemorative Arts Trust, which promotes ‘for public benefit education in and appreciation of the arts and crafts associated with letter design and letter carving for memorials and other lettered works’. The trust offers apprenticeships, a ‘Journeyman Scheme’, lettering workshops, advice on commissioning unique works of lettering in wood, stone or other materials, and holds a collection of lettered works at seven sites across the UK, from Scotland to Wales, via Lincolnshire and Birmingham. If you have an interest in lettering, type design or typography, then this is the place for you. And if your enthusiasm for such aspects of the visual world is more general, but no less keen, the MacDonald Gill show is well worth a detour.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in