Porto Heli

I am standing on the deck of a 100ft schooner that was built in Normandy in 1931 by Gerald and Sara Murphy, the golden American couple who invented the south of France as a summer playground and who were in the forefront of artistic and literary Parisian life of the time. More important, Ernest Hemingway and Scott Fitzgerald trod on the exact spot where I’m standing, relaxing rather, surrounded by children and grandchildren, but feeling a bit of a midget compared with the types that once sailed on the Weatherbird.

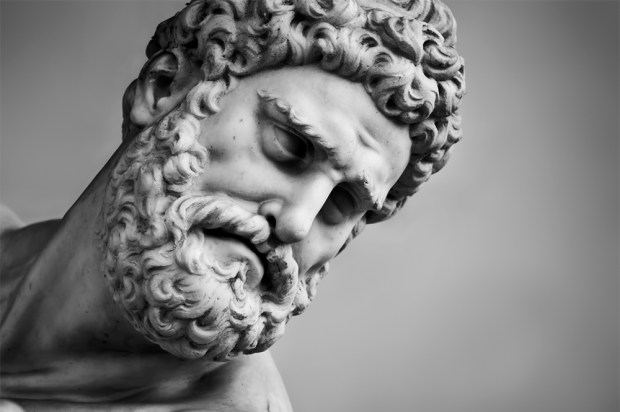

I’ve chartered her for the month of August and the dreaded upcoming birthday but, far more important, in order to play Papa Hemingway, who once appeared chez Murphys with his wife Hadley and his mistress Pauline in tow, as happy a threesome as the Riviera had seen that particular summer. (Alas, no such luck for the poor little Greek boy.) Gerald Murphy, a very talented painter, had designed a flag for Weatherbird that Picasso, another close friend, admired greatly: a stylised eye in black and white that appeared to wink as it fluttered. Gerald was tall and sandy-haired, wore beautifully cut clothes and was very handsome. Sara was a classical beauty and the couple had three children. They were rich and talented and lived better than anyone, surrounded by beautiful things and gifted artists. Thus the stage was set for the Greek tragedy that followed, the loss of their two boys from disease, and eventual genteel poverty and death. So what else is new? Gerald and Sara were lucky not to live to see the present Côte d’Azur, the sweaty overbuilt hellhole inhabited by crooked Russians and Gulf billionaire camel drivers.

Gerald and Sara were the inspiration for Dick and Nicole Diver in Tender Is the Night, the hauntingly sad novel that broke Fitzgerald’s heart when it was panned by critics, but is now considered, along with Gatsby, as his masterpiece. In one version, the novel begins in the south of France, when Rosemary Hoyt spots Dick on the beach and tells her mother, ‘I fell in love this afternoon.’ Neither Gerald nor Sara were best pleased, but said little. They always indulged poor old Scott and understood the hell he was going through with the nutty Zelda, his alcoholism and money problems. Cole Porter, another close friend, was among the first to visit in the summer, a deserted time in Cap d’Antibes and the tiny little beach of Garoupe, where Gerald had built Villa America. If that wasn’t paradise back then, I don’t know what is.

Just compare today’s parties among the shady people of Monaco and Antibes with those given by the Murphys on board the Weatherbird. Cole and Linda Porter, Papa and girls, the Fitzgeralds, John Dos Passos, Archibald MacLeish, Dorothy Parker, Picasso, Fernand Léger, Igor Stravinsky, Jean Cocteau (whom Hemingway christened Cocktail) and others of their ilk. Amanda Vaill wrote a brilliant biography of the couple in 1995, and called it Everybody Was so Young. A much earlier book by Calvin Tomkins was titled Living Well Is the Best Revenge. Both books recalled the enchanting period of the Twenties and early Thirties in France and in America, a time that ended with the aftermath of the crash and eventual return to earth by Gerald and Sara, the death of their sons and that of Fitzgerald, aged 44 in 1940.

‘How cruelly the world needs the beauty of his mind,’ lamented Gerald at his funeral. Only 30 people showed up in the rain at his graveside on 27 December. Zelda was not allowed to attend, and he was also denied a Catholic burial as the Church considered his books immoral. Scott had done some silly things in his life, but who with his great talent hadn’t? Hemingway got it right when he told Sara Murphy, ‘Poor Scott, no one could ever help him but you and Gerald did more than anyone.’

I guess we take death more seriously today, and when cheap old hacks die their funerals are oversubscribed. But back to Weatherbird and happier times. As I walk her deck I can see Scott drunkenly moaning that Sara is being beastly to him because she’s focusing on Hemingway and his Spanish tales, and Gerald asking him to stop being childish. Which brings me to my own child, John Taki, and the loss of Reas, his pointer, that has left us all bereft. JT asked us to keep Reas in Gstaad while he went bicycle racing in Spain, and Reas joined our other two dogs running around the Bernese hills. Reas had been with my boy all his adult life. From San Diego to Brooklyn, to Rome and now Paris. She would sneak away down to the Palace hotel where the cooks would give her goodies and Andrea the concierge would then ring us and tell us she was waiting to be picked up in the lobby. Two weeks ago, Reas disappeared, something we were used to, but this time with a difference — I had a terrible premonition about it. After looking for her for the best part of the day, a gamekeeper found her at dawn. She had fallen in a crevasse and broken her neck. We brought her ashes on board Weatherbird for JT and had a drink in her memory along with all the other greats who have sailed on board this wonderful classic, starting with Papa. I hope something of theirs rubs off on me, but I’m afraid it will only be the alcohol consumption.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in