It’s 2023 and the Western education system is broken, the culmination of a process that has its roots as long ago as the turn of the century.

The elite universities have surrendered to Woke ideology, censorship, political pressure, and layers of bureaucracy that have encrusted them like barnacles on the undersides of an ocean fleet. To get funding, they have become conduits for corporate avarice, exchanging a platform for pushing technologies, medical interventions, and other pet products for billions in tribute. The students, supposedly the beneficiaries of all this, are too enslaved by smartphones and bombarded by propaganda to critically analyse what they are being taught, or even to notice much what they’re being taught.

It’s a catastrophe and very likely unfixable. There has to be another way.

Paul Frijters, an academic economist, author, and adviser with an employment CV that features universities in Australia, the UK, and elsewhere, and his wife Erika, a public health expert and consultant, proposed the answer: they would create an entirely new kind of advanced learning institution from scratch that provided its students with a broad grounding in the social and health sciences, drawing its inspiration not from the 2023 degree factories, but from a contemporary adaptation of the ancient Greek academies, and the pre-1950 European colleges.

Easier said than done.

Even attempting to make it happen involved huge risk: it meant a seismic lifestyle change for both of them, a future fogged by uncertainty, 80 hours or more of work every week (after giving up cushy academic jobs), and the chance of a lifetime to go from affluence to poverty. They decided to do it anyway, and Minds That Dare: Restoring Western Education – a True Story is the tale of their battle against the odds to make the dream a reality.

Frijters is joined as coauthor by Sienna Baker, a recently minted graduate from the Australian mainstream university system and already an accomplished writer in her early 20s. Throughout the book, Frijters and Baker provide alternate viewpoints on the unfolding plot, providing the reader with distinctly different perspectives and writing styles. Baker was already well-steeped in the problems of the conventional university. Her own degree was stuffed like a Christmas turkey full of social justice-oriented content, so much so that she had trouble learning anything at all for the first two years. The Communist Manifesto was required reading for her Social Work program, not just once but three times for three separate undergraduate courses. And that, from one of Australia’s elite universities.

Together, Frijters and Baker have penned an engaging, silkily written tale, crafted with unmistakable (but probably accidental) shades of Peter Mayle’s 1980s classic A Year in Provence. However, while Mayle’s book was a cosy memoir about settling into a new cultural milieu, Frijters and Baker have a higher calling: underneath the witty, warm narrative there is a struggle going on for the future of academia.

The new academy envisaged by Frijters and his early associates, which came to be called Academia Libera Mentis (ALM), would be small, targeting a total capacity of no more than 100 students, and it would nurture them to ‘become co-owners of both the future of their society and of ALM itself’. The reason for a small student population is partly that it doesn’t require a massive administrative bureaucracy. As Dr Gigi Foster, like Frijters an academic economist and one of the project collaborators puts it: ‘I can just pick up the phone and say, “Hey Paul, I thought about this, what do you think?” and I don’t have to go through 17 different committees and put together a business case and get the stamp of approval from the bureaucracy just because I want to change one assessment from being 10 per cent to 15 per cent.’

Some of Frijters’ small team of academics had been harassed, and in some cases canceled, by the existing system. Among them was Dr Tjeerd Andringa, who found himself on the wrong end of a university bureaucracy for the crime of training his students to think critically and independently. The team also included Foster, one of the stars of the Covid resistance and a pocket battleship ideally suited to an endeavour like ALM. When the discussion came around to articulating the new institution’s guiding principles, it was she who posed a simple but brilliant question:

‘How were the classics educated? How did they come to be classics?’

This leads to a lengthy and entertaining dialogue between Frijters and Foster about the lives of Socrates, Machiavelli, Charles Darwin, Voltaire, Metternich, and Russian and Eastern luminaries.

Now, the reader is hooked. This is really interesting stuff to be thinking about.

Out of the evolving discussions during the early months of 2024 came some broad principles. The students had to be trained to think for themselves, but to get there required a spirit of open inquiry that existed well before the 21st Century and has been lost in the years since.

‘We did not even plan to tell students our opinions on climate change, Covid vaccines, lockdowns, gender identities, racism, or foreign wars: by teaching students the ancient skills of reflection and cross-validation of knowledge, we could equip them with the ability to work out for themselves what was truth and what was propaganda. If we were honest with them, they would become honest with themselves.’

The ALM team knew what the overarching principles were for how and what they wanted to teach, but how to organise it into detailed course content? Whatever system was to be used had to be a departure from the siloed approach of the modern university with what Frijters refers to as its ‘tribes and sub-tribes’ in each discipline, a system that ‘makes it nearly impossible to weed out nonsense.’

They came up with the idea of ‘integrated knowledge’ assembled from different times and endeavours, from Socrates and the Greeks, the American revolutionaries, modern business and industry, and a heavily curated selection of old and new academic traditions. These inspired about 100 basic ideas, or what the authors refer to as ‘anchors’.

‘Alongside those anchors, we would add basic data and basic skills that were very similar to what one learns at existing universities. Those included basic statistics, basic methods of science, presentation skills, writing skills, world literature, and many other lessons learned by humanity over the centuries that are recognised the world over. We needed to teach these because they were essential for our students to function and expand their own worldview, but these would not be things that would set us apart.’

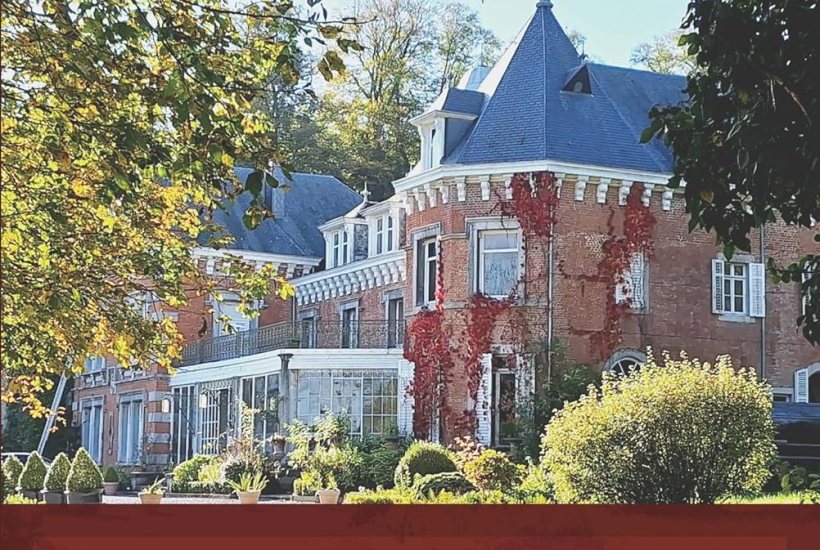

Castle Hodbomont

Along with the euphoria of reviving a great teaching tradition came some terribly hard practical realities. For example, there was a pressing need for a campus. Paul and Erika hit upon the idea of buying a disused castle, of which there was an abundance in Western Europe. After a lot of driving around and inspecting a number of castles, they settled on Castle Hodbomont in the Belgian Ardennes, using a large part of their life savings to make a successful bid, and took up residence there in March 2024.

Once installed there, they could start focusing on what was needed to get the place ready for its first students, and as it turned out, a lot was needed. The leaky roof had to be patched up and pests brought under control, including the voracious rats which had a finely-honed partiality for groceries and for chewing through electricity cables. (Later, they solved the rodent problem with a couple of cats.) The electricity cable issue was more complicated though because after more than a century of tinkering by different owners, the whole place needed to be rewired. The lucky new owners also had to get familiar with the local culture, the local politics, and the local regulations, and survive the suspicious attention of a watchful local media, all in a language (French) that they spoke and understood poorly. Frijters describes how the protagonists were swamped for 80 or more hours a week dealing with the administrative and legal minutiae, all in French. ‘I had come to hate Mondays. For some reason, most bureaucrats send out their bad news correspondence just after their first coffee of the new working week.’

By now, the reader is being swept along by the story. The narrative is immensely entertaining, at least for this reader, who didn’t have to personally wrestle with the problems and do the work.

Bootcamps

The team chose to conduct week-long bootcamps as an alternative selection device to replace the lengthy testing and administrative procedures conducted by mainstream universities. Alongside the bootcamps was a ‘Healthy Campus’ initiative, a volunteer program in which prospective students and other backpackers could get free accommodation and food in exchange for six hours of work per day.

‘By July, the project had a steady stream of volunteers who came to beautify the grounds, paint the interior, help with renovation projects and cooking, and experience the academic environment. They came from all over the world and were usually between 18 and 35, with a few above 50.’

Robert Frijters, Paul’s son, who has a penchant for organising people and massaging their various personalities to overcome frictions and achieve the required results, became the work foreman.

A real highlight of the book is its vivid depictions of classroom discussions that the reader is invited to join as an observer: there are classes on creative story-writing, and using the Socratic method to critically analyse climate change data. There are classes in which students are placed in situations where they must creatively solve high-level problems, such as how to interrupt an inbred and incompetent Swedish ruling dynasty in the early 19th century. In each case, the reader is able to observe the interactions between the students and teacher and between the students themselves, see how they work through the problems and actually learn some genuinely fascinating stuff. In essence, the reader gets to become a student for a while.

Interestingly, despite the refreshing mingling of non-academic pursuits with the academic in the form of dance and theatre, there is little mention of sport, which is surprising in view of Frijters’ own CV, which includes extreme cycling, hiking and marathon-running.

Problems

The problems don’t stop at the classroom door – oh, by the way, a lot of classes take place outdoors when the weather is nice – there are the inevitable in-class problems: students who metaphorically throw their toys when they are confronted with sensitive topics that might challenge their entrenched viewpoints.

Since the academic staff, students and volunteers form a community that lives, works, studies and eats together, there are the inevitable conflicts that arise that are common to communities. There is, for example, among the volunteers at one point a Latino clique that couldn’t relate to vegetables when it came their turn to prepare dinner for the group.

Minds That Dare is a slick piece of work whose slickness doesn’t disguise its flaws. On several occasions in the book, the authors take time out to make character assessments of each other and there are unnecessarily lengthy analyses of the progress of their mutual understanding and ability to work together. Indeed, this could well be the very first book ever written in which the two coauthors have a good old hack at each other. It is difficult to understand the relevance of this sparring, which comes over as a series of couples therapy sessions without the therapist. In defence of the authors, it could be explained as intentionally providing an up-close-and-personal glimpse into the difficulties that arise between people in the ALM team when the academic setting is also a self-contained community. Fair enough. The academics and students are stuck with each other, and they need to work things out. It is also consistent with passages Frijters quotes from one of his favourite sources on statecraft, Machiavelli, denigrating the dishonesty of ‘court flatterers’. Still, it’s a distraction and breaks up the flow of the essential narrative.

Despite such peccadillos, the story of ALM told in this book is an ongoing one, and I trust this first literary effort only represents its first chapter. The book is itself a story of courage, intellectual richness, persistence and hope, and even if the reader is not directly involved with education or even interested in it, the narrative stands on its own as an absorbing piece of story-telling.

Perhaps the biggest challenge of all to ALM is getting the word out there to prospective students, particularly as there is almost no one on the team who likes marketing or professes to be good at it. Yet ALM clearly has much to offer its students: not only the unique learning experience itself, but the physical context, since Castle Hodbomont is smack in the middle of a picturesque and historic part of Western Europe – it was a major battlefield in two world wars – with quick access to Amsterdam, Paris and other great cities on the backpacker trail. With so much going for it, ALM may not be a secret for long.

Minds that Dare can be purchased from Amazon.