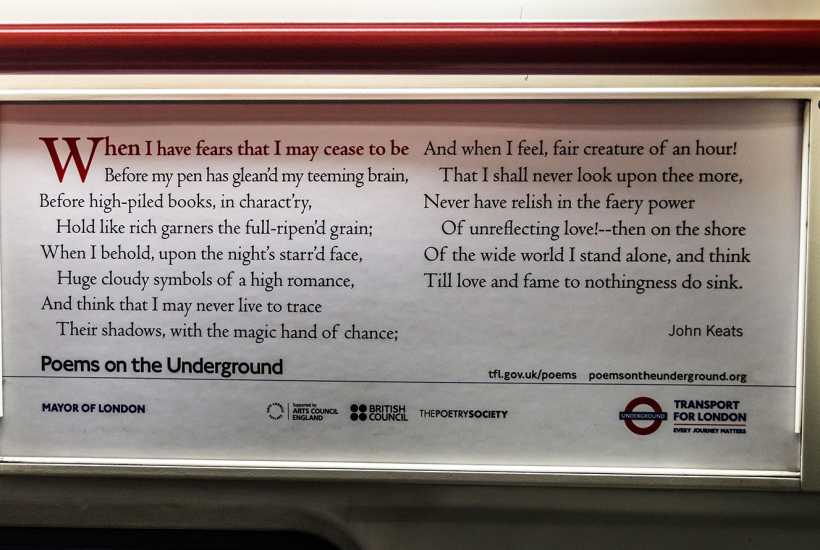

The idea for Poems on the Underground was thought up by a New Yorker 40 years ago this month. This may surprise you, given that the posters are synonymous with London. But then again, the creative possibilities of a transport system tend to be lost on its native commuters. Judith Chernaik, a lecturer in English literature, had recently relocated to the capital when she fell in love with the Tube: ‘Compared to New York it’s bliss – clean, safe and fast, too… if things are working of course.’

Ozymandias was soon riding the lines from Aldwych with Robert Burns

In As You Like It, Orlando goes around the Forest of Arden dangling sonnets for Rosalind from trees. Those sonnets are mostly dire, but it occurred to Chernaik, while studying the text at her neighbours’ play-reading group, that good poems might be dangled before Londoners to break up the advertisements. The scheme would later be rolled out across other major cities of the world.

‘Both Shelley and Keats are really behind the whole idea,’ Chernaik elaborated in a vibrant documentary for Radio 4’s Artworks, unwilling to give Shakespeare full credit. Shelley was a fellow advocate of the idea that poetry can change the world. Keats was ‘so desperate’ to have his poems read outside of his social circle that it seemed a pity to deny him his wish posthumously.

Amazingly, the managing director of London Underground agreed to post a handful of poems – the choice was initially left solely to Chernaik and her neighbour friends – and even to match whatever they could raise for the initial printing. Ozymandias was soon riding the lines from Aldwych with Robert Burns (‘Up in the Morning Early’ was a good choice for the office workers), a plum-cheeked William Carlos Williams, Grace Nichols and Heaney’s ‘The Railway Children’. Poor Keats would alight at a later stop.

The programme was an unalloyed delight. Many of the contributors had lovely stories of being transfixed by poems that seemed to speak directly to them. Chernaik, now 91 but sounding half her age, was disarmingly eloquent. While we were given little sense that Poems on the Underground is at risk of financial extermination (there is even, we learned, a department within TfL dedicated to creating ‘moments of delight and surprise’), its power is limited by the bounds of human concentration. Forty years on, with carriages brimming with phones, it was good to be given new reasons to look up.

Artworks is celebrating a second big anniversary this month, and that is the birth of punk in 1976, or thereabouts. Purists may quibble over the precise foundation date, but 1976 was the year the Damned released their debut single and the year the Clash played their first gig. Presenter Chris Packham, saviour of badgers and birds, runs with it in his new three-part series.

Packham, who, whether you support his activism or not, has to be one of the most skilful presenters on the BBC, credits punk with teaching him defiance against authority. ‘When punk turned up,’ he recalls, ‘being different was an asset.’ But this isn’t really that type of series. In fact, Packham very quickly takes a back seat, for this is A People’s History of Punk, which can mean only one thing: vox pops.

This would usually be sufficient to make me switch off. Bleurgh! Other people’s opinions. But whoever did the research has managed to find some very well-placed former punks. It is particularly good to hear from artist Alex Michon, who happened not only to have attended the first ever Sex Pistols gig (Central St Martins, November 1975), but also one of the first major London gigs of the Clash (Royal College of Art, November 1976).

What it delivers is a chatroom of sexagenarians, reminiscing on the wild days of their youth

In both cases, her memories revolve predominantly around what the bands were wearing: dishevelled school uniforms in the case of the Sex Pistols, besplattered art-school boilersuits in the case of the Clash. The fact that it was the fashion that first captured her attention makes what happens next sound like it was made to be – she landed a job making clothes for the Clash’s Joe Strummer.

The series promises ‘violence, bodily fluids and plenty of foul language’, but what it delivers is a chatroom of sexagenarians, reminiscing on the wild days of their youth. This is what the producers wanted, of course, punk being about giving a voice to the voiceless, and it is where the real interest of the series lies. The music – even the culture – of punk is practically incidental. The question is more: what happened to the punk fans? Their stories, while not consistently earth-shattering, will tell you much about why rebellion is a youth’s game.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.