It’s been a less than stellar year for trans activists. Shortly after taking office last January, President Trump signed an executive order withholding federal funds from any school that permits biological men and boys from playing on women’s sports teams.

Then in June the US Supreme Court upheld a Tennessee law banning the use of puberty blockers and hormones for the treatment of young patients suffering from so-called gender dysphoria and seeking to change their gender identity.

And on Tuesday the Supreme Court heard arguments in two cases brought by transgender athletes seeking to overturn laws in Idaho and West Virginia barring biological boys and men from playing on female sports teams at the state and local level.

While much of the three-hour hearing, extraordinarily long for the high court, focused on arcane abstractions of class certification and the troublesome legacy of conflicting case law, the overall import was clear. The conservative majority seemed inclined, for the moment at least, to leave in place laws in 27 states that ban biological men and boys from playing on women’s sports teams.

“One of the great successes of America in the past 50 years has been the growth of women’s sports,” Justice Brett Kavanaugh remarked during a colloquy with one of the lawyers representing the transgender athletes. “There are a number of groups who believe that allowing transgender women to participate will undermine that success. If a (female) athlete doesn’t get a medal or make all league, there is a harm there. There are a lot of people who are concerned about that.”

The two cases before the court were brought by Lindsay Hecox, now a college senior in Idaho and Becky Pepper-Jackson, a high school sophomore in West Virginia. A federal district judge initially ruled against Pepper-Jackson’s complaint, but that decision was overruled by the Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals in Richmond. Hecox won favorable rulings both at the district court level and at the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals in San Francisco. Both Idaho and West Virginia appealed to the Supreme Court, which agreed last year to hear the cases.

Permitting transgender girls to compete on girls’ teams would “eliminate sex separated athletics entirely,” said Michael Ray Williams, the Solicitor General of West Virginia, urging the court to uphold the state ban. “In the end, this court must recognize the physical differences between men and women. And they are enduring.”

At bottom, the dispute involves a clash of two different and entirely irreconcilable world views. On the right, sex is biological and immutable, on the left it is whatever an individual decides it is. It’s a dispute over custom and ritual, social organization and cultural identity that at times seems even more politically powerful than crime, health care and general economic conditions.

And, in the sense that where a politician stands on the question is a window on his or her baseline political views, it is a signal issue.

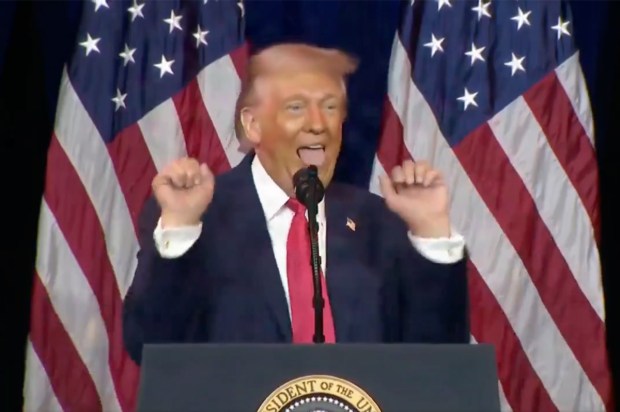

It even arguably decided the 2024 president election. One of the most powerful campaign ads of the 2024 presidential race took Kamala Harris to task for her support for taxpayer funded sex change operations for prison inmates and illegal aliens. “Kamala is for they, them, President Trump is for you,” the add proclaimed to devastating effect.

In her 2022 Senate confirmation hearing, Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson declined a request from Senator Marsha Blackburn that she define what a woman is.

“I can’t… I am not a biologist,” she answered.

And now, in its own formalized and ritualistic way, this is the world that the federal court system and Supreme Court jurisprudence finds itself embroiled in. At least two federal circuits, the Seventh and the Ninth, have identified transgender persons as a protected class, subject to invidious discrimination by the government, in need of special protection. One circuit, the 11th, has declared that sex is a function of biology and has rejected the transgender argument that sexual identity is immutable and objectively determined.

At different points during the hearing both Kavanaugh and Chief Justice John Roberts wondered aloud whether the best course of action for the court would be to allow individual states to decide what their policies should be. That would of course let laws stand in states that have banned transgenders in girls’ sports.

The court’s three liberal jurists, Elena Kagan, Ketanji Brown Jackson and Sonia Sotomayor seemed all too aware that the court’s conservative majority likely would not reverse the bans.

And so, in their back and forth with the attorneys, raised the possibility that a more tailored approach, where transgender athletes might show through use of testosterone lowering drugs that they posed no unfair competitive advantage.

Absent a ruling against the bans, which is highly unlikely, what activists on the left want is for the court to avoid providing a definition of sex based on biology that might then serve as a basis for legal challenges against the 23 states that permit biological men to compete in women’s sports.

“I urge the court not to decide the case without a definition of sex,” said Joshua Block, an ACLU lawyer representing Pepper-Jackson.

The court will likely rule in the matter sometime before the current term ends in June, just as the mid term congressional elections are heating up. Observers on the right and left will be watching closely to see just where the Supreme Court draws the line.