On December 6, I published an article on Substack, later also by The Spectator Australia, decrying the then imminent social media ban for those under 16. I concluded my article thus:

‘Nice internet you’ve got there, be a shame if we stopped letting you use it.’ First, they came for the under-16s etc. The only ones it protects is the government and their collaborators, and it protects them from criticism. And, they hope, from revolution. We shall see.

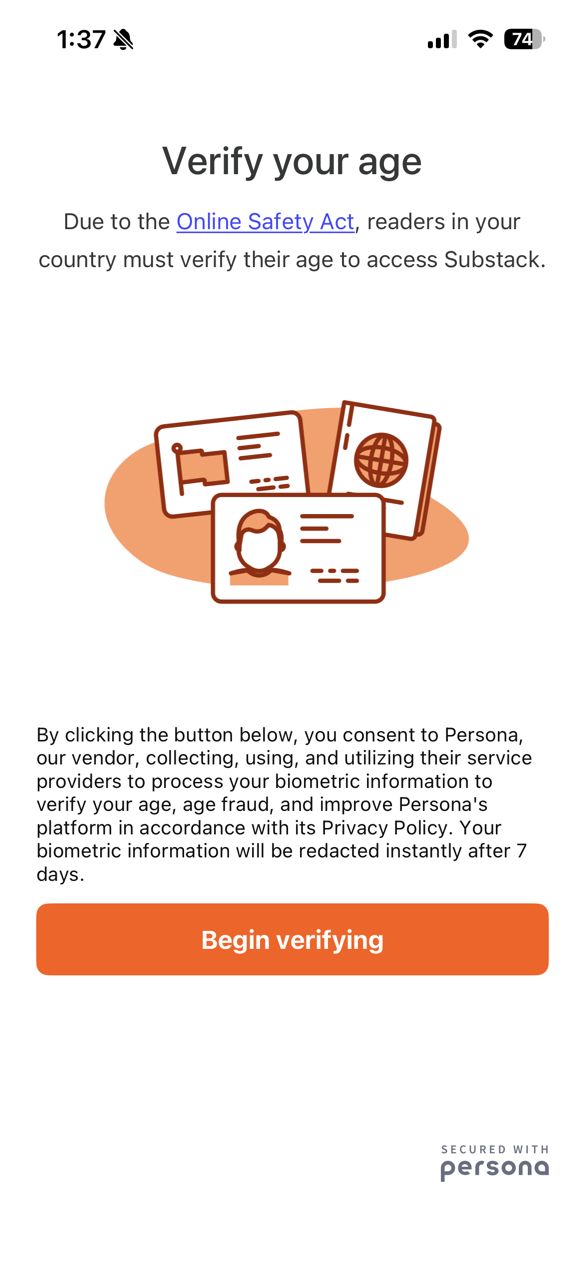

Two weeks later, on December 19, while trying to log in to Substack, I was met with a demand to provide biometric data:

I don’t think it is necessary in a functioning democracy for writers or readers to be asked to provide biometric data like photos of my face or fingerprints or whatever it was that ‘persona’ was going to demand in the following screens if I had clicked through to ‘begin verifying’.

Maybe in a totalitarian state where ruling authorities had trouble with dissidents who wouldn’t stop criticising them, it might make sense for companies to get out ahead of the strict letter of the law and start asking for this info.

Substack was not one of the platforms mentioned by politicians and bureaucrats as being harmful to those under 16. But hey, who cares! Substack is complying anyway. How many others will do the same?

(Substack does have an explanation about why they have complied with the law for both the UK and Australia which you can read here.)

As far as I’m concerned, Substack can go to hell.

395 free ‘subscribers’ to my modest publication have now been regretfully informed that I won’t be using Substack anymore. I understand lots of other writers are taking the same stand.

It’s disappointing for me as a writer to lose the gratification of the handful of ‘likes’ I get for my essays, and the comments from sympathetic readers. Even more disappointing is that I can’t log in to read some great writers who are also critical of the ruling authorities in this country once known as Australia. I think I’m getting a small taste of what the under-16s might be experiencing – those who follow the rules that is – as they lose a network of friends overnight.

Tom Ravlic in The Spectator Australia wrote about how the ban might be affecting teenagers with rare medical conditions.

During the dark troubles of the recent past, the knowledge of the existence of like-minded souls was one of the few shining lights that kept many of us going. For those who were isolated and shunned, for no greater crime than prudence, Substack joined together a community of dissidents who lent support to each other.

All sorts of intersecting groups used social media to enrich their lives. Now, it seems inevitable that many will find isolation again, perhaps with tragic consequences.

What we see playing out is teenagers thrown off social media, and writers and readers of alternative media asked for biometrics. We see angry crowds and prime ministers booed. We saw businesses shuttered and people confined to quarters.

One is tempted to believe that our bone-headed leaders just do not have what it takes to make decisions and take actions having thought through the expected consequences, and weighed them against possible unintended consequences.

Of course, another interpretation is that indeed they do have what it takes to make decisions in light of the possible consequences, intended or not. And that what we see playing out has indeed been foreseen and accepted.

Of the two possibilities, the former is to be hoped for, and the latter ruefully assumed until proved otherwise.

Either way, the dissidents will not be silenced.