Catholics, along with other Christians, will soon celebrate the birth of history’s most famous Jew, Jesus of Nazareth. It is a tragedy that the Church’s relationship with the Jews has been characterised by hatred. However, after overcoming centuries of antisemitic prejudice, the Church enjoyed positive relations with Jews until left-influenced theology threatened to send it back down a dark path.

For centuries, Church teachings fuelled hatred: labelling Jews ‘cursed’ for rejecting Jesus, blaming them for his death, and promoting ‘supersessionism’ – the idea that Christians replaced Jews as God’s chosen. This justified pogroms, expulsions, and laid groundwork for the Holocaust. The 1950s marked a turn. Pope Pius XII removed offensive terms like ‘perfidis’ from Good Friday prayers. Then, the Second Vatican Council’s Nostra Aetate (1965) declared Jews and Catholics spiritual siblings with shared roots. It condemned hatred, persecution, and antisemitism.

These reforms should have warmed Vatican ties with Israel.

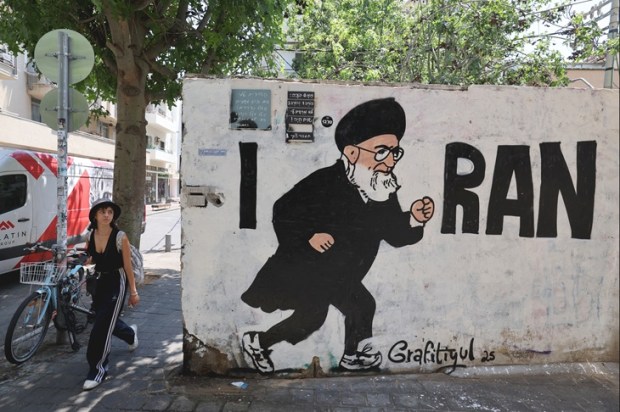

However, nearly three more decades passed before the Holy See recognised Israel in 1993. Popes have visited the Holy Land, wept at the Western Wall, and sought Holocaust forgiveness, but also embraced Palestinian leaders, prayed at Israel’s security barrier under ‘Free Palestine’ graffiti, and advanced Palestinian statehood.

These mixed signals confuse many. The key culprit is the rise of left-wing ideologies in Catholicism, especially liberation theology.

Born in 1960s-70s Latin America, it aimed to champion the poor but adopted Marxism, reviving antisemitic tropes under progressive guise. It often cast Jews and Israel as oppressors in the Marxist oppressor/oppressed binary.

The Holy See, exemplar of Joseph Nye’s ‘soft power’, grounds ties with Israel in God’s irrevocable promise to Abraham’s descendants. Nostra Aetate revolutionised this by rejecting supersessionism and the notion that Jews are cursed. Pope John Paul II embodied this. A boyhood friend of Jews (including a Holocaust survivor), he visited Auschwitz in 1979, wept at the Western Wall in 2000, called Jews ‘our elder brothers in faith’, and invoked St. Paul to say, ‘The gifts and the call of God [to Jewish people] are irrevocable.’

This theology spurred the 1993 recognition, burying mistrust and prompting Holocaust apologies. Cracks emerged from traditionalist fringes who clung to conversion prayers or rehabilitated deniers. But the ideological left, via liberation theology, proved more corrosive.

Post-Vatican II, liberation theology permeated seminaries, urging priests to combat poverty through a ‘preferential option for the poor’ for earthly liberation, viewing God through the oppressed’s eyes. Noble at heart, it soured by embracing Marxism’s class warfare.

Theologians recast the Bible as an anti-oppressor manifesto, turning Jesus, a Torah-observant Jew, into a proto-Marxist rebel against the Jewish establishment.

This explains liberationists’ neglect of Nostra Aetate’s anti-antisemitism. They sideline Jewish suffering, obsessing over ‘oppressed’ Palestinians and vilifying Israel as a colonial oppressor. One theologian warped the Abrahamic covenant into a conditional pact: with the Jews losing their rights to the land because of their failures to ‘do justice’. This ‘new supersessionism’ swaps decided charges for injustice accusations, relativising the covenant and caricaturing Judaism as legalistic relic. Another stripped Jesus of Jewishness, making him a generic revolutionary, thus erasing Judaism’s uniqueness in an ‘oppression-liberation’ haze.

The outcome is a subtle antisemitism that delegitimises Jewish faith, history, and statehood. Israel appears not as Biblical fulfillment but violent Old Testament revival. Liberation theology today shapes much Catholic activism. John Paul II and Benedict XVI rebuked its Marxism; but Francis, shaped by Peronist liberationism, praised its ‘spiritual beauty’.

Francis personifies Catholicism’s tension. He affirmed that, ‘To attack Jews is antisemitism, but an outright attack on the State of Israel is also antisemitism.’ Yet in 2014, he prayed at the West Bank barrier amid ‘Free Palestine’ graffiti, dubbed Mahmoud Abbas an ‘angel of peace’, highlighted Palestinian ‘roots in the land’, and in 2015, canonised two Palestinian nuns as the Vatican recognised Palestinian statehood, distressing Israel. These echo liberation’s oppressor-victim lens through which Israel’s defences are labelled ‘concentration camps’ (a Vatican quip on Gaza), and Jewish self-determination drowned in ‘universal justice’.

Though few liberationists embrace overt antisemitism, its Marxist influence is insidious. It downplays the Jewish covenant, mocks Judaism as obsolete, and pits Israel as Goliath to Palestine’s David. It redirects Church soft power against Jews, swaying voters, NGOs, and diplomats toward ‘anti-oppression’ over covenant loyalty. Amid rising global antisemitism, these views unwittingly stoke antisemitism’s flames.

Yet hope endures for Jewish-Catholic relations. Nostra Aetate, John Paul II’s legacy, and Church doctrine affirm the irrevocable covenant, thwarting hard supersessionism. Heeding Scripture, and seeing Jesus as a Torah-loving Jew not a Marxist revolutionary, would repel antisemitism. But in identity politics’ grip, Marxist-inspired liberation theology prompts Jewish-Catholic tensions.

Once deeming Jews perfidious, the Church now hails them as beloved siblings. To sustain this, leaders must deploy soft power with theological precision, not ideological haze.

Marxism corrupts Catholic thought, as it does all.

To save Jewish-Catholic relations, to recover the vision of Vatican II, and Popes John Paul II, and Benedict, the Church must champion authentic Catholic values over destructive leftism.