Being a Scottish sailor in the 1960s and 70s, I had more than a passing interest in fine looking ships, fine looking women (especially in mini skirts), and the pursuit of efficient propulsion power.

For those into trivia, 100 years earlier, one of the fastest clipper ships of the time was the 85m Cutty Sark, a Net Zero ship, built in the Denny shipyard, my hometown of Dumbarton, Scotland.

Cutty Sark was a term expressed by Robert Burns in his poem Tam O’ Shanter where the heavy drinker Tam on his horse Maggie on the way home in the dark was pursued by a young witch Nannie with a ‘Cutty Sark’ – a short skirt or mini skirt.

A statue of the topless young witch has pride of place on the Cutty Sark bowsprit in Greenwich London. This spectacular ship was built for speed and while she achieved 17.5 knots in a 24-hour period with a very favourable wind, her fastest record of 73 days from Sydney to London only represented 7.5 knots on average, carrying 900 tonnes of wool. Ask any long-distance sailor if 7.5 knots is impressive and they will tell you yes! On the Cutty Sark itself, for visitors, there are computer stations where you can actually simulate sailing the ship from Sydney to London, on a screen with differing wind speeds and directions.

People ask me if solar panels could boost the speed of a sailing ship, the answer is yes, but only marginally. If the sun was shining and no wind was blowing, a solar panel array of 120 square metres (hard to fit on a sailing ship superstructure) could generate 20kW and push a fine hull like the Cutty Sark at up to 4 knots from a standstill, whereas her 3,000 square metres of sail area would achieve 17.5 knots in a strong breeze. So perhaps solar could reduce the 73-day record to 71 or 70 at best if a minimum speed was attained during the doldrums.

But the Industrial Revolution in terms of ship design, driven largely by the Scots with coal-fired steam propulsion via paddles on wooden ships, then propellers, then steel ships became competitive by 1850 and started the decimation of sailing ships by larger vessels on scheduled routes, to more and more destinations globally.

The last operating commercial sailing ship, the Pamir, was commercially uncompetitive by 1949.

In the warship scenario, the UK ruled the waves with the world’s largest navy with an all-sailing vessel, Net Zero fleet. They were around 38 years slower than commercial vessel operators to adapt to steam-powered propulsion, only in the late 1800s, having to reluctantly admit that it was the way of the future. The Royal Navy’s role in protecting the burgeoning commercial fleet and ports in a widespread empire was a key element in their decision-making. Naval warships even with auxiliary sail power were no longer built by 1900.

With hundreds of other sailing enthusiasts, I attended the Wind Propulsion of Commercial Vessels symposium in London in 1980 where one bright idea was large helium box kites raised to 2-3,000 metres, catching higher winds and connected to a small wire winch on the ship’s bow. While it may have been a hazard to low flying aircraft, hang gliders, and bird life, it never took off despite promising trials.

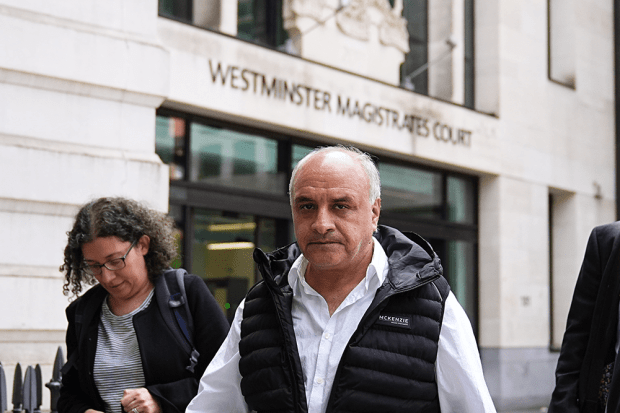

Even the late Duke of Edinburgh, a keen and experienced naval officer, who gave the keynote speech at the symposium, encouraged the assembled multitude in their endeavours.

At the same symposium, I was impressed by an aviator who developed a fully battened ‘Galant Rig’ on a 45-foot freedom ketch with free-standing masts and who convinced me and another marine industry tragic to venture down to Southampton and do a trial on the Solent. He impressively showed us how to hoist and trim these sails, let go of the moorings, and exit out of a marina with only one hand (the other holding a glass of scotch for the whole exercise). Despite this magnificent display (and a scotch or two), this design did not attract industry manufacturers or sailing purists.

The fact is that wind propulsion of commercial vessels has been, and continues to be, investigated for ships. You will see a variety of ships with rigid sails, Flettner rotational masts and sails with solar panels, the best reported to be reducing emissions by up to 10 per cent, only over a portion of the total voyage. None of these solutions are yet commercially realistic for production designs, but they do tick the box for the company’s corporate image in window dressing, striving towards the hallowed zero emissions that sailing ships already had.

Global shipping contributes 3 per cent of global emissions the activists may scream, but it carries 95 per cent of our global freight and activists should be promoting shipping instead of road freight, which generates 20 to 40 times the emissions per tonne/kilometre. Australia for instance, whose coastal highways carry most of the nation’s freight and coastal shipping does not exist because it doesn’t attract votes. Never mind the 1,300 road deaths and 18,000 serious road accidents and the $50bn road costs that occur annually around Australia’s coastal highways. The fools steering the nation’s transport policy need replacing.

Total solar power boats, like the catamaran Tûranor PlanetSolar, was the showcase piece at the 2010 United Nations Climate Change Conference sitting as a shining example of solar power’s future.

With its 537 square metres of solar panels, generating 93kW of power only when the sun is high on a clear sky. The best sector of her years of global sailing was where she managed a 2013 transatlantic crossing of 22 days, at only 10 knots, but without any payload at all.

Many commercial day ferries have solar arrays on the fly-bridge above the wheelhouse, which contribute to the AC and DC via inverters for the wheelhouse air-conditioning, navigation and communications equipment, providing a useful safety alternative to communications in case of a power blackout.

I have been involved on the sidelines of methanol, ammonia, hydrogen, and LNG propulsion of ships. I am involved in nuclear, which leads the field in ship propulsion with 162 ships in operation and many more on the drawing board, because no other energy source comes closer on cost/kW or energy density. Plus there are no emissions and you don’t have to carry many hundreds of tonnes of fuel and can carry that weight in revenue-generating cargo. How good is that?

So with my hand on my heart and after designing commercial vessels for 47 countries, I can say with total conviction, that powering a ship, or a country, with only wind and solar renewables will not work.

Only a fool would make that choice.

That ship has sailed.