When I was a young union official, angry, often obnoxious, and knee-deep in the Robe River dispute at the ripe old age of 22, I was quoted in the local newspaper saying something I believed without irony:

The only difference between a working man and a slave is his right to withdraw his labour.

Though it had the power to motivate people, it was not a slogan. It was a principle. The strike was not theatre. It was an attempt at leverage in a high-risk industrial environment – one that became riskier with every armoured car of strikebreakers driven through the picket lines. Fifty people who took part in strike action I organised at Robe River never worked again in their lives. It was a heavy burden for a young kid.

Industrial conflict was hard and often unpleasant. But it was honest. You knew who represented whom. You knew what was at stake. And you knew that the capacity to stop work was the final safeguard of freedom in a system built on wage dependence.

The Robe River dispute was where the edifice of industrial relations as it once existed began to change. Looking back, Whitlam had already made it clear that the Labor Party would consciously broaden its coalition toward the expanding educated middle-class, modernising its image, and diminishing the structural dominance of union machinery. The working-class did not cease to matter, but it was no longer electorally decisive in the way it once had been. We just didn’t believe him at the time. For many, myself included, it would take until the Crean/Copeman deal before that penny would finally drop.

This was the resolution brokered between Simon Crean (then President of the ACTU) and Charles Copeman (CEO of Peko-Wallsend). The media at the time unironically referred to it as ‘peace in our time’, the famous statement of Prime Minister Chamberlain on the eve of the second world war. Many of us on the ground also saw it in this light, but as the appeasement of an aggressor.

Robe River was not simply a bitter industrial fight. Western Australia had seen plenty of those and still had plenty to go. What was different was the positioning of political authority around it. What I noticed was not outright betrayal, but hesitation. The language of solidarity remained, though increasingly void of the courage required to execute it.

From my Pilbara vantage point, the loss of government by the Keating regime appeared less like an electoral cycle and more like the culmination of a long realignment. We were trapped between the HR Nicholls Society, backed by the Liberal Party, and a Labor movement that had embraced deindustrialisation as economic orthodoxy. The unethical fantasy that Australia would be stronger if we purchased goods we used to manufacture from countries with poverty level wages. In practice, this meant industrial capacity weakened, skilled workers lost their jobs, and production moved to labour conditions we would not tolerate at home.

I left Australia during that period. Partly for adventure. Partly for experience. Partly for because it felt easier to start again somewhere else than to watch everything collapse at home. Youth makes an exit feel decisive, but in truth I was wrong on both counts.

The Howard era is acknowledged as a golden era of tax cuts for ‘battlers’ and exploding home equity, a prosperity that, for many, replaced the dignity of a trade with the volatility of an asset bubble. Any negative implications of battles over ‘WorkChoices’ is often used as narrative cover for the market-based Enterprise Bargaining system ushered in by Keating and cemented by Rudd in a marketplace where deindustrialisation had already removed many of the working-class jobs.

On September 11, 2001, I saw the Twin Towers fall from Mexico City. The world hardened. Yet the undercurrent of globalisation not only persisted but accelerated even while Western Civilisation entered an unprecedented era of terrorism. By 2008 I returned to Australia, having left the increasingly volatile environment of Europe for the relative stability and serenity of Saudi Arabia, with a wife and children, seeking something I had once taken for granted: stability, structure, a place that still felt anchored.

Immediately, the changes I had sensed earlier seemed fully formed. The Labor Party, which had once drawn its instinct from industrial labour, was now unmistakably professional and middle-class in composition. It was run by Kevin Rudd, our soon to be former US Ambassador. Like the Liberal Party, it was staffed at parliamentary level with lawyers, economists, diplomats, policy advisers, and union officials whose careers were administrative rather than industrial, theoretical rather than physical.

When Kevin Rudd proposed the Resource Super Profits Tax, the Mining Tax, set at 40 per cent, I felt it as a final betrayal. In my mind this was yet another assault on the working-class jobs that remained after deindustrialisation had already moved all our manufacturing and textile jobs overseas. Not only did I see it as another class assault, but a further attempt by the metropolitan centres of Australia’s pacific southeast to cash in on the labour of the north and the west while keeping its hands clean of red dirt.

In fact, the background noise of my life has been the complaints by the urban middle-class about how much you can earn in a fly-in fly-out job, taking you away from your wife and kids, to work in 50-degree heat, while never considering that they too could enjoy that privilege if they applied to do so.

By the time of the Covid pandemic, nearly 15 years later, the union movement had become something else again. The CFMEU, inheritor of the mantle and much of the administrative infrastructure of the old Builders Labourers Federation, with the support of the ACTU, aligned with government vaccine mandates against the will of its membership.

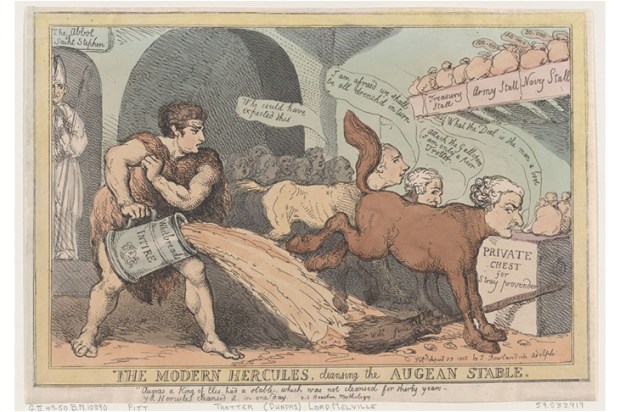

This isn’t an argument for or against mandatory vaccination in a pandemic, it is an observation that the union movement was no longer an expression of the will of their members. They had become institutional actors. They were stakeholders within a broader governance architecture. Their survival and influence depended on proximity to power more, it appeared, than their mobilisation against it. The principle I championed in my youth, the right to withdraw one’s labour, seemed now to exist only as a rhetorical instrument.

Political orphanhood does not mean the loss of a vote but the loss of institutional intimacy.

Union membership, approximately 50 per cent when Gough Whitlam held power, has fallen from approximately 19 per cent in 2007, under Prime Minister Kevin Rudd, to a meagre 12.5 per cent of the workforce by the mid-2020s. Far from being a working-class voice in Canberra, the union movement is today little more an arm of the Labor government in the workplace. Today the working-class are spoken about more often than they are spoken with.

The middle-class moral vocabulary has also changed. Institutional speech is rife with terms like inclusion, transition, resilience, and diversity. None of these are hostile in themselves, but all drip with condescension driven down from above, not emanating from the workers themselves.

In this environment, the rise of minor parties such as One Nation is better read as a symptom than a solution. While the major parties are led and staffed predominantly by middle-class professionals, One Nation presents itself as culturally and socially closer to working-class voters.

When it was observed by those in position of power that Hanson ‘left school at 15 without completing high school’, it highlighted the total lack of understanding endemic in many areas of Australia’s public service and political ranks. Education is no guarantee of intellect, and institutionalisation is no guarantee of wisdom. On the contrary, many of the policies and culture-war issues the educated middle-classes support require a distinct disconnection from biological and cultural wisdom.

Political orphanhood does not produce revolution in a country like Australia. It produces drift. It produces protest votes. It produces volatility. It produces a quiet search for recognition.

What happened in Australia, though filtered through our industrial relations culture, is not exceptional. Variations of the same realignment can be seen in Britain with the rise of Reform and figures such as Rupert Lowe, in France and the Netherlands through insurgent populist movements, and in Germany and Spain through growing volatility in traditional party systems. In each case, the working-class remains electorally visible but has become unmoored from the institutions and parties that once claimed to represent it.

Along with freedom of speech, association, movement, and political affiliation, I still fervently believe in the right of the working-class to withdraw their labour. What I stopped believing long ago was that the Australian union movement is a true and faithful servant of the Australian working-class.

When the institutions built to defend a class evolve beyond it, political orphanhood follows.

And orphaned constituencies do not disappear. They search.