England’s turnaround in literacy and learning should give every Australian Education Minister pause. It proves that academic reform is not only possible but is relatively easy to achieve.

However, the uncomfortable truth is, even if Australia replicated England’s academic achievements it still would not be enough. We cannot fix a nation without first addressing the culture wars and that is a reform too many of our politicians seem unprepared to address.

It is not rocket science.

England went from 11th to 4th in the world for reading by doing what we know works: returning to phonics, insisting on a knowledge-rich curriculum, restoring classroom order, and demanding evidence-based teaching.

Under Minister of State for Schools, Sir Nick Gibb, there was a decade-long reform program that broke the stranglehold of the progressive dogma that asserts children learn best through discovery and group projects. He replaced it with structured literacy, teacher-led instruction, and high expectations for all students, regardless of background. According to the 2021 Progress in International Reading Literacy Study, England’s 10-year-olds scored higher than in any other country in Europe or North America. England now produces the top readers in the Western world, and behaviour in schools has improved dramatically. Students from disadvantaged families are the biggest winners.

The extraordinary success has been led by the likes of Katharine Birbalsingh, Principal of Michaela Community School in Wembley, which draws students from disadvantaged backgrounds and gets as many children into Oxford and Cambridge as does Eton. It shows that the basics can be fixed. The English model proves that evidence-based instruction of phonics, structure, discipline, and explicit teaching work.

England’s reforms dealt with how children learn, something desperately needed in Australia. However, Australian students also face a much deeper problem, which is the content they are actually taught.

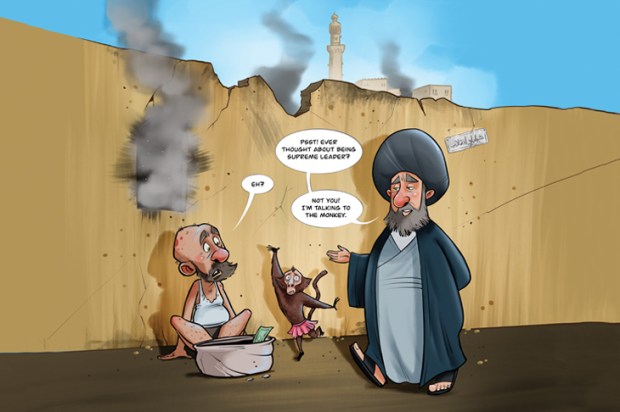

The National Curriculum, and a multitude of popular curriculum materials providers, present a narrative in Australian classrooms telling students they are born into either privilege or oppression, that their country is unjust, and that their future is bleak because of an impending climate apocalypse.

While we might be able to fix the problem of reading attainment, we still have to confront the problem of what our students are reading. What good is literacy if the content being taught breeds despair, guilt, and grievance?

In Australia, we have allowed ideology to shape curriculum content. The ‘Sustainability’ curriculum priority tells children that human progress is a threat to the planet. The ‘Indigenous priority’ divides them by race and heritage. The Humanities and Social Sciences units teach national shame rather than pride.

So yes, we must copy England’s commitment to evidence and order, and urgently so. But we must also be brave enough to confront the messages we are embedding in the lessons themselves.

When students are told that hard work and merit are myths, that success is privilege, and that their country is a source of harm, we shouldn’t be surprised when they leave school anxious, cynical, disengaged and dependent.

Australia needs not only structured literacy, but structured meaning. Never more obvious than now, children must be taught what is worth loving about their country: the rule of law, the fair go, democracy, and freedom.

We must restore discipline, reinstate phonics, and insist on evidence-based and knowledge-rich curricula. But the even greater battle is for the purpose and meaning of education itself.

Colleen Harkin is the National Manager of the Institute of Public Affairs’ Schools Program