Some of the more baroque policy noises currently drifting out of New York City under its new Democratic Socialist mayor, Zohran Mamdani, offer a useful preview of what is likely to wash up on Australian shores courtesy of the Australian Greens. Think of it as political fashion week: whatever staggers down the ideological runway in Brooklyn today will be hastily stitched together for Brunswick and Balmain tomorrow.

The Greens have long been afflicted by a distinctive form of intellectual sloth. Rather than do the dull but necessary work of designing policy that might function under Australian conditions, they prefer to import ideas wholesale from overseas movements and declare them morally superior by definition. Imitation may be flattery, but imitation of failure is self-harm. When the imported policy is already demonstrably broken, the problem is not originality but poor judgment.

At the next election, housing will almost certainly be the first cab off the rank. This is familiar territory for the Greens, who spent much of the last parliament insisting they alone possessed the moral courage to fix the problem. Voters replied with polite but unmistakable rejection. The Greens’ offering looked less like a governing program than a student manifesto written sometime after midnight. A normal party might have paused for reflection, but the Greens, of course, are not a normal party.

Like many movements built on moral certainty, they are psychologically incapable of accepting that voters might have rejected their ideas because their ideas were bad. The more soothing explanation is that they simply did not go far enough. And so, the lesson drawn from defeat will not be to moderate but to radicalise.

Enter the New York City mayor’s model. It is irresistible to the Greens: maximalist rhetoric, minimal economics, and a conveniently endless supply of villains. If rents are high and homes scarce, it must be because someone, somewhere, is making a profit. And profit, in the Greens’ cosmology, is the original sin from which all social evils flow.

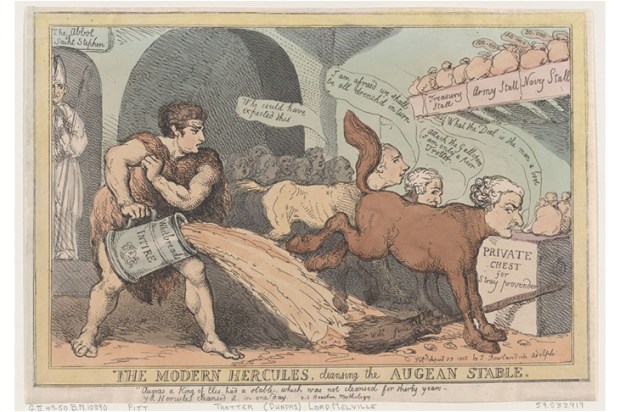

A serious housing policy would require grappling with dreary and unfashionable realities: land supply, construction costs, financing risk, planning approvals, and infrastructure sequencing. None of these fit neatly on a placard or into a viral clip. It is far easier to borrow the Democratic Socialists of America playbook – a warmed-over remix of Marx and Engels but repackaged with friendlier fonts and better branding.

Declare housing a human right, remove it from the market, impose rent controls, punish investors and then express performative outrage when the whole contraption collapses under the weight of its own contradictions. This is always sold as compassion. In practice, it is vandalism conducted in softer language.

Wherever rent controls and investor crackdowns have been tried, the pattern is relentlessly familiar: private capital retreats, maintenance is deferred, new construction evaporates, and governments eventually find themselves forced to socialise the losses. Buildings decay, waiting lists balloon, and the poor end up worse off than before.

The Greens adore this model because it absolves them of responsibility. If investors flee, that proves they were immoral. If supply contracts, blame capitalism. If rents rise, the controls were not strong enough. Policy failure becomes evidence not of error but of insufficient ideological zeal. Reality is not a constraint but something to be denounced.

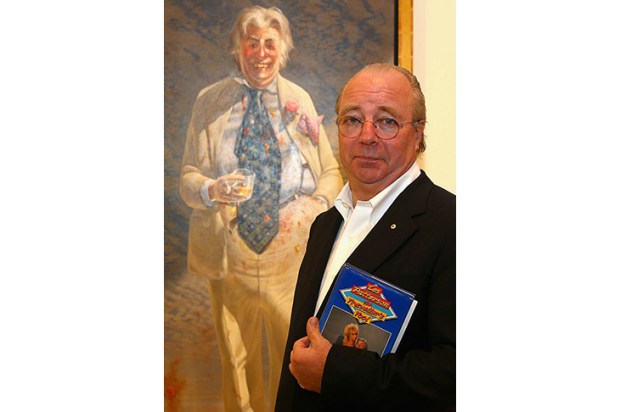

No figure embodies this disposition more enthusiastically than former Greens MP Max Chandler-Mather. He has refined a style of politics that combines absolute moral certainty with breezy indifference to how markets actually function. His pronouncements read like a greatest-hits compilation of populist fallacies: rent freezes that magically increase supply, mass public acquisition schemes serenely unconcerned with cost, and ritual denunciations of investors who, inconveniently, supply most of the rental housing in which Australians actually live.

Chandler-Mather’s real talent is theatrical. Housing is framed not as a complex policy challenge but as a morality play. Landlords are villains, renters are victims, and the Greens are the only adults in the room. Financing, risk, and long-term asset management are dismissed as bourgeois distractions. Eliminate profit, and housing will apparently self-organise into abundance, like a socialist fairy tale rendered in brick veneer.

This dovetails neatly with another fashionable delusion gaining traction in Australian policy circles: hiking capital gains tax. From think tanks to Treasury briefings to activist economists, there is a growing belief that Australia can tax its way out of a housing shortage. The Greens are enthusiastic collaborators. Cut the CGT discount, raise effective rates, then act surprised when investment enthusiasm collapses.

Push the capital gains tax high enough, and fewer projects stack up, fewer upgrades occur, and fewer rental properties are built. Australia already smothers housing investment with stamp duty, land tax, GST, compliance costs, zoning controls, and an increasingly hostile regulatory climate. Adding yet another impost may feel morally satisfying, but it actively discourages the activity that needs to be encouraged.

The Greens’ fallback position will be entirely predictable. If private capital refuses to cooperate, the government should simply replace it. This fantasy glides past the awkward truth that public housing, or social housing under its newish cuddly title, is expensive to build and ruinously costly to maintain. Once the ribbon is cut, it becomes politically irresistible to skimp on upkeep, producing decaying stock and ballooning liabilities. Every jurisdiction that leans heavily on public housing ends up with long queues, deteriorating buildings, and cavernous maintenance backlogs. The Greens’ answer will always be the same: more spending, more taxes, more control.

What makes all this particularly galling is that it carefully avoids the real causes of Australia’s housing shortage: planning restrictions, glacial approvals, infrastructure bottlenecks, entrenched hostility to density, and persistently high immigration levels. Fixing these requires technocratic reform that is unglamorous and politically uncomfortable. The Greens show no appetite for such work. It is far more emotionally rewarding to denounce speculators and investors than to explain why a modest apartment block can take a decade to be approved.

The point Australian voters should keep firmly in mind is that the Greens are not proposing an experiment. They are proposing to repeat, almost line for line, policies that have failed elsewhere, and to scale them nationally. This is not radical innovation; it is ideological nostalgia.

If Australians want fewer homes, higher rents, decaying public housing, and a permanent politics of blame, the Greens offer a clear path. If Australians want more housing, lower costs, and policies that work, they will need to look elsewhere and stop confusing moral posturing with competence.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.