It’s funny how implicated we are in the places from which we take our bearings. Memories of the Lexington-Concord bridge, site of a War of Independence battle, swathed in mist, not far from the home in Lincoln, older than the president of that name, of a friend who edits a literary magazine at Harvard. Part of the uncanny mystique of America when you first clap eyes on it is its familiarity, as if its mightiness was apprehended as a form of going home. All of which comes to mind because Ken Burns, who back in 1990 –– aided by voices and stills –– turned the American Civil War into an engrossing epic that sent people back to Shelby Foote’s narrative history and was thrilling in its evoked sense of reality. Well, now he has made the supreme prequel: The American Revolution, available in six two-hour parts on SBS OnDemand.

This one will contemplate the paradoxes and contradictions; Washington’s defeats and the two terms for a President. The astonishing revelation of Jefferson’s Declaration of Independence: ‘All men are created equal’ – despite the slaves he owned – and then the truly revolutionary phrase, ‘the pursuit of happiness’. The great Canadian critic Northrop Frye – the author of Anatomy of Criticism – said happiness was not something that could be achieved by pursuit. Gertrude Stein said America was the oldest country on earth because it had been living in the twentieth century since the Civil War.

In The American Revolution, this is taken a step further. There are the wigs and the eighteenth-century clobber, but also the birth of a discernibly American democracy. Burns has put it together with the help of various voices: Meryl Streep, Samuel L. Jackson, Claire Danes, Josh Brolin and Ken Branagh.

Infotainment is a small word for what Burns does; he enacts it. He has, after all, covered everything from The West to Hemingway with all sorts of diversions – jazz, baseball, you name it. In between there was Leonardo and the prospect of a documentary series on Winston Churchill. Will he get Anthony Hopkins to do the great bulldog voice? Richard Burton was Churchill’s own choice for the early sixties’ documentary The Valiant Years, and there’s an obvious resemblance with Hopkins. But there is a clear parallel with enthralling non-fiction in Burns’ work, and we should admit the grandeur of the craft that makes it possible. There’s a sumptuous coffee table book to accompany it, just as there used to be for old-style BBC culture talk like Kenneth Clark’s Civilisation or Robert Hughes’ The Shock of the New, though they used the single starry voice where Burns uses an ensemble.

The American Revolution coincides with the Sky TV serialisation of Peter Shaffer’s Amadeus, starring Paul Bettany as Salieri, the great antagonist who does his best to destroy Mozart, and Will Sharpe as the surpassing genius. You can watch the whole of the five episodes at a stroke.

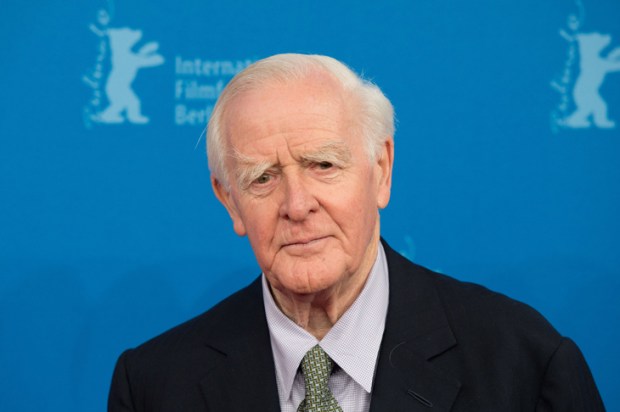

All of which is congruent with the largesse of Christmas. Memories of reading the trickiest of the le Carré novels, The Perfect Spy – the one about the conman father, which pushes in the direction of art – within coo-ee of water and bush.

Michael Innes didn’t make it to my last list of diversions, though he’s inclined to top the list. You can captivate yourself with Len Deighton in The Ipcress File and Funeral in Berlin, and you can be totally taken with the Tudor detective stories of C.J. Sansom, which make the case for a self-reforming English Catholic church, which in turn reflects Eamon Duffy’s The Stripping of the Altars. The hero is a humanist repelled by the thunderous dogmatism of the competing Reformation and Counter-Reformation sides.

But high on my list of supremely readable trash fiction are the Michael Innes novels with the immensely cultivated detective John – later Sir John – Appleby, a bloodhound who is likely to quote Milton (if not Aeschylus) at the drop of a hat. The first of the Innes novels is Death at the President’s Lodging, and then there is Hamlet, Revenge! in which a famous actor, a distinguished statesman, and the Duke who is everyone’s host, all play their roles (often edged with ancient grievance) in a production of Shakespeare’s great histrionic mirror of a play.

During the war, J.I.M. Stewart, Appleby’s creator, was Jury Professor of English at the University of Adelaide. He was asked to give a lecture about Australian literature and declared there was none, so he would talk about D.H. Lawrence’s Kangaroo instead.

He also had a career, under his own name, as a serious novelist, and these novels – admired by Philip Larkin and Kingsley Amis – are in an elaborate neo-sub-Jamesian style and are sometimes touched by homoeroticism and are certainly ‘camp’ in the archaic sense. On the other hand, his Oxford History of English Literature, Vol. XII (Joyce, Kipling, etc.) and his single-volume study of Conrad are written in a brilliant, rapid style, utterly lacking in affectation.

Of course, you might want to read an effortlessly relaxing crime spinner such as Ngaio Marsh (full of her sense of theatre) or Josephine Tey’s defence of Richard III from a hospital bed, The Daughter of Time. She also wrote The Franchise Affair, once compelling, that drips with yesterday’s attitude to girls.

Then again, that eminent political scientist Dennis Altman, a man who read The Magic Mountain under the supervision of Hannah Arendt, is a passionate devotee of Agatha Christie.

The difficulty with trash fiction – or what we read as the late Amy Witting said ‘to grovel’ in – is not likely to convince us as a form of truth (for what that’s worth). It’s fascinating to learn that Margaret Drabble, when she wants to really relax, picks up a Reacher novel – Lee Childs’ prose has its own vitality and the hero is a joy if you’re in the mood. Perhaps there’s something similar at work in the John Grisham books (Camino Island and its sequel Camino Winds) about that unscrupulous but humane bookseller, Bruce Cable. Of course, we’re attracted to books that are difficult to put down, which also woo us with the grace of language. Raymond Chandler does this, and so does a classic detective story like Margery Allingham’s The Tiger in the Smoke. Jane Harper’s success with bush noir is related to her ability to create characters, but that’s also a vulnerability.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.