The rise in One Nation’s share of the vote is causing a major political realignment.

Their rise is coincident with public frustration at the deterioration of internal security. These security failures led us to the massacre at Bondi Beach. We hope, but do not know, if this is where the story ends.

The election of the Albanese government has ushered in a new era of incompetence in the management of the basic security that citizens expect from their government.

It is a government narrowly focused on identity politics which means appeasing particular parts of the population to harvest their votes. Many of these targeted voters are dissatisfied with their share of the nation’s wealth and want politics to confiscate and redistribute the income earned by the more successful.

The dissatisfaction shown in the opinion polls runs deeper. It also reflects a recognition of the Albanese government’s incompetence in economic management. The government has demonstrated no concept of how the wealth it parcels out is created – and, hence, is clueless on how to keep that engine of income operating.

Labor’s assumption is that wealth creation just magically occurs, regardless of the government in place and irrespective of its policies. As a result, we have decisions being made that create irreparable harm by slowing or even preventing resource development, as in the case of the gold mine thwarted by claims that it might disturb a confected blue-banded bee. And we have other decisions that will cause lower levels of savings through taxation of superannuation.

It is doubtful that any government minister is aware of the central role of savings and investment in future living standards. The taxation of superannuation and redirection of capital to overseas locations and to income-sapping venues like renewable energy is illustrative of a mindset that simply treats income as a constant river of revenue to be diverted to voter-pleasing causes.

Ministers and the Keynesian-infused Treasury officials who advise them would see no difference between a dollar spent on investment, personal consumption, or government handouts.

Yet it is investment supplied by savings that drives incomes.

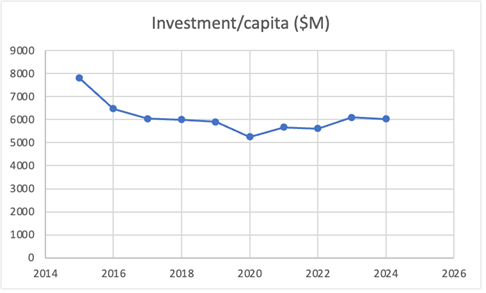

Australian income growth has been especially fostered by mining booms during the late 1960s, early 1970s, and during the 30-year period from the mid 1980s. Since then, investment has flagged. In per capita terms – and excluding the renewable investment that is dependent on subsidies (and actually destroys productive investment), real annual per capita investment fell from around $8,000 to $6,000.

There is no sign of this trend being reversed, and its long-term effect is a lowering of living standards, perhaps by as much as a quarter, from what they would otherwise be.

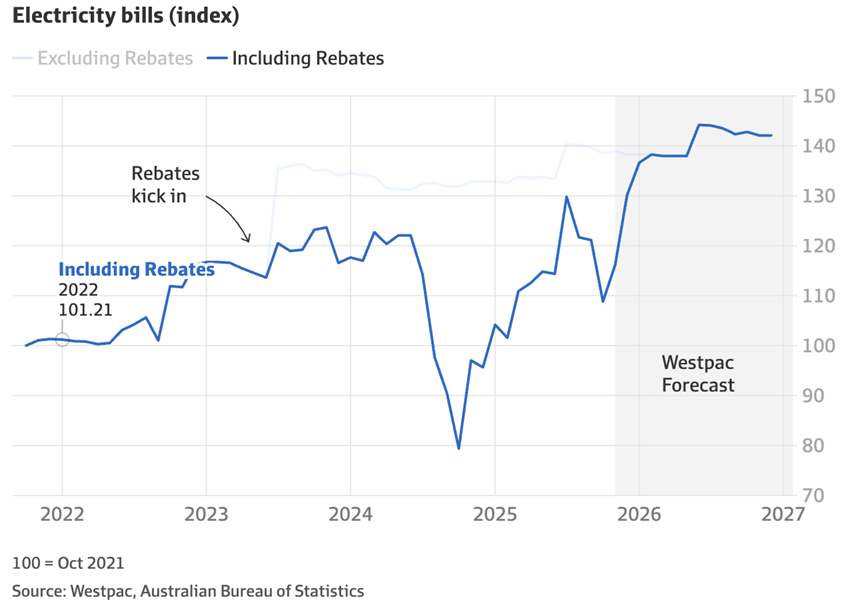

Nothing illustrates the damage imposed by politicians’ ideologically driven hubris more than the power costs forcing the closure of value-adding smelting and agricultural processing plants across the nation. And as Westpac shows, the Albanese-Bowen Plan to reduce electricity prices by replacing coal with wind, solar, and batteries has predictably backfired. Electricity bills will be 42 per cent higher this year than in 2022.

This has nothing to do with the cost of coal and the plant that converts it to electricity – coal itself is so amply available that, as has been the case for a century, its cost of mining has steadily declined as technologies have improved.

A further high-profile symptom of government-induced disaster is housing. Australia has infinite land availability and a highly efficient (mainly non-unionised) housing and land development workforce. Yet over the past 15 years, house prices (which were already among the highest in the world) in relation to income levels have increased by 30 per cent. That outcome is solely due to restrictive state government land availability policies, which could be readily combatted by the Commonwealth.

In democracies, political parties that spend money they don’t have to buy votes and provide favours to those considered to be minorities generally are favoured by electorates. That is, until they are no longer so favoured, a turnaround that occurs once the policies are recognised for the net harm they cause.

This was the case in the 1980s Anglosphere with the elections of Thatcher, Reagan, Lange-Douglas, and Fraser. This has been repeated with Trump in the US and is threatened with Farage in the UK.

Following that pattern has been the gradual rise in One Nation’s popularity in response to recognition of the Albanese government’s incompetence in economic management, propelled by terror in the name of self-described Islamists. One outcome is the dramatic realignment of politicians in the Liberal and National Parties.

But, as those seeking to circumscribe the free expression of opinions are all too aware, without harnessing democracy to free speech, the change that can allow such transformations ranges from difficult to almost impossible.