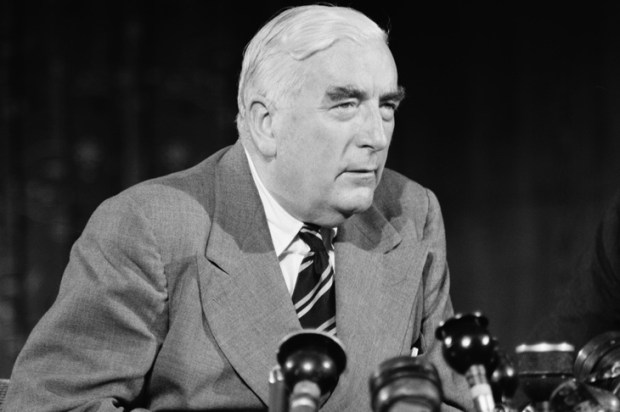

Robert Gordon Menzies remains one of the most consequential figures in Australian political history.

We need another leader capable of his long-term vision and stability to form a prosperous 21st Century Australia.

Serving as Prime Minister from 1939-41 and again from 1949-66 – Australia’s longest continuous term – Menzies presided over a period of unprecedented social transformation, economic expansion, and institutional re-definition.

His government’s policies reshaped manufacturing, nurtured the automotive industry, restructured education, managed Australia’s evolving international trade relationships, and laid foundations for a new Australian middle class.

While not revolutionary in the radical ideological sense of some later leaders, his reforms were patient, structural, and enduring, positioning Australia for decades of prosperity.

Economic Reform and the Foundations of Post-War Prosperity

Menzies inherited a nation emerging from war into a precarious economic climate. Infrastructure was strained, the population was comparatively small, and its economic reliance on primary exports – particularly wool, wheat, and minerals – made it vulnerable to external shocks. His core objective was clear: broaden the economic base, modernise industry, expand human capital, and reduce dependence on singular export markets.

His Liberal governments were unapologetically committed to private enterprise, yet more pragmatic than doctrinaire. Menzies believed in state facilitation of enterprise rather than a rigid laissez-faire approach. He strengthened the finance sector, established institutions like the Reserve Bank of Australia in 1960 to stabilise monetary policy, and supported immigration to expand the workforce and consumer base. These foundations catalysed sustained economic growth across the 1950s and 1960s and enabled a vibrant manufacturing landscape.

The Car Industry and Manufacturing: Building a Nation of Producers

Central to Menzies’ economic vision was industrial diversification. Australia’s manufacturing base prior to the second world war was limited; wartime necessity had accelerated domestic industrial capacity and Menzies seized the opportunity to carry that forward into peacetime.

The Automotive Sector

The car industry became a symbol of modernity, aspiration and self-reliance. Though the first Holden had been launched in 1948 under the Chifley Labor government, it was under Menzies that the sector truly expanded and embedded itself in the national economy. His government protected the industry through tariffs, incentives and industrial planning, enabling companies such as Holden, Ford, and later Toyota and Chrysler to invest and manufacture domestically.

The automotive sector was not merely about producing cars; it was about fostering an ecosystem of supply chains, component manufacturing, steel production, engineering expertise, and employment. Thousands of Australians entered stable industrial work, wages grew, and Australia became one of the most motorised societies in the world. Cars symbolised suburbanisation, mobility, and the aspirational middle class life Menzies championed.

Broader Manufacturing Growth

Manufacturing during the Menzies period diversified beyond automobiles. Consumer goods, textiles, appliances and machinery production flourished. High tariffs ensured domestic industries could grow shielded from overwhelming international competition. Though later generations would debate whether protectionism entrenched inefficiency, at the time it was viewed as nation-building policy. It allowed industries to mature, expanded employment, and reduced economic vulnerability tied solely to agricultural exports.

Education Reform: Investing in Minds as Well as Factories

Menzies is often rightly remembered for his commitment to education as a pillar of national development. Unlike some conservative leaders fixated narrowly on economic output, Menzies saw education as the civilising, uplifting force for a democratic nation.

Menzies dramatically expanded federal involvement in higher education. Prior to his government, universities were under-funded and limited primarily to elite classes. Recognising the demands of a modern industrial and scientific economy, Menzies’ government boosted funding, commissioned key inquiries (notably the Murray Report), and invested in new universities. The Commonwealth Scholarship Scheme enabled unprecedented numbers of Australians – including those from modest backgrounds – to attend university.

This expansion was transformational. It facilitated greater social mobility, produced engineers, teachers, scientists, and administrators essential for national growth, and helped transform Australia culturally and intellectually. In this sense, Menzies work revolutionised modern Australia: he wanted an educated citizenry capable of leadership, innovation and civic responsibility.

Menzies also increased Commonwealth involvement in schools, particularly through funding science laboratories during the Cold War era. Education was framed as essential in the geopolitical contest as well as for domestic prosperity. His initiatives paved the way for later governments’ comprehensive school reforms.

Reforming Culture

One of the most significant legacies of the period was mass post-war immigration. While the initial framework was shaped under Labor, Menzies sustained and expanded it. Millions of migrants from Europe reshaped Australia’s cultural landscape, workforce and demographics. The Australian economy gained labour, skills, and cultural vibrancy, laying foundations for a multicultural nation even as official policy was slower to liberalise racially.

Menzies strengthened social welfare institutions. Though not as sweeping as later social democratic expansions, his government increased pensions, developed social housing and anchored the notion that government played a role in providing security while encouraging self-reliance.

Menzies cultivated a moral vision centred on family, community, civic responsibility, and aspiration. His rhetoric appealed to stability and dignity but also to opportunity. The ‘middle class’ was not merely an economic category but a moral and civic force in his political philosophy. He believed prosperity was a means to stable democratic citizenship.

International Trade and Positioning Australia in the World

Menzies governed during a critical transition in global trade. The British Empire – long Australia’s principal trading and cultural anchor – was shifting, and the world economy globalising.

Menzies balanced loyalty to Britain with pragmatic diversification. The 1957 Commerce Agreement with Japan was transformative. Just over a decade after the second world war, Australia signed one of its most significant trade agreements with its former enemy. This deal opened Japanese markets to Australian raw materials and allowed Australia to benefit from Asia’s economic rise. It also symbolised a maturing independent foreign economic policy.

Through regional alliances, trade agreements and institutional engagement, Menzies helped reorient Australia towards the Pacific and Asia without severing ties to Britain. His leadership in the Colombo Plan further demonstrated his recognition of the region’s strategic and economic importance.

Comparisons with Other Reforming Political Leaders

Understanding Menzies’ legacy is enriched by comparing him to other major reformers.

With John Curtin and Ben Chifley

Curtin and Chifley laid much of the groundwork for national planning, wartime mobilisation, and early post-war reconstruction. Where Curtin forged independence in foreign policy and national unity, Chifley set early industrial frameworks. Menzies built upon and institutionalised many of these transformations. Where Labor initiated bold shifts, Menzies consolidated them into stable structures.

With Margaret Thatcher

Unlike Thatcher, Menzies was not an ideological deregulator. Thatcher dismantled old industries and curtailed unions to liberalise markets. Menzies, instead, supported protected industrialisation and cooperative economic expansion. Both, however, championed aspiration, private enterprise, and middle-class empowerment.

With Lee Kuan Yew

Lee Kuan Yew, like Menzies, focused on education, discipline, and building a capable state. Both leaders believed in strong institutional frameworks, national unity, and pragmatic economics. However, Menzies operated within a robust liberal democratic setting, while Lee employed a more directive, centralised model.

With Hawke and Keating

The Hawke-Keating reforms of the 1980s-1990s liberalised the economy, floated the dollar, and dismantled tariff protection – ironically transforming much of the system Menzies helped build. Yet they did so from a position of strength made possible by earlier decades of manufacturing expansion, infrastructure development, and human capital growth that Menzies had fostered. Thus, Hawke and Keating modernised an economy Menzies helped industrialise.

In each comparison, Menzies emerges not as a radical disruptor but as a patient architect – constructing durable frameworks rather than shock reforms.

Lessons from Menzies for Modern Liberal Leadership

Contemporary Australia faces dramatically different challenges: climate transition, technological disruption, geopolitical uncertainty, cost-of-living pressures, productivity stagnation, and cultural fragmentation. Yet Menzies’ leadership philosophy offers enduring guidance.

1. Build, Don’t Just Manage

Menzies was a builder: of institutions, industries, and national identity. Future leaders must embrace nation-building once more. This means investment not only in roads and rail but in digital infrastructure, renewable industries, advanced manufacturing, and sovereign capability. Protectionism of the 1950s cannot simply be revived, but strategic industrial policy can ensure Australia remains a producer nation rather than merely a supplier of raw commodities.

2. Education as the Central National Asset

If Menzies could see education as strategic in the mid-20th Century, it is exponentially more critical today. A future Liberal vision should emphasise world-class accessible public and private education, lifelong learning, vocational prestige, and innovation ecosystems connecting universities to industry. Just as Menzies expanded access to universities, modern leaders must expand access to digital literacy, STEM and future industries.

3. Social Cohesion and Shared Opportunity

Menzies was conservative, but not callous. He believed prosperity should enable dignity. Modern Liberal leadership must similarly recognise that social stability rests on fairness, opportunity, and inclusion. Housing affordability, equitable access to services and thoughtful migration policy should echo the spirit – not necessarily the exact form – of post-war nation building.

4. Pragmatic International Engagement

Just as Menzies moved beyond exclusive reliance on Britain, modern leaders must navigate a world defined by US-China tensions, Indo-Pacific strategy, and multilateralism. Australia must diversify trade, invest in regional partnerships and build economic resilience. A forward-looking Liberal vision should blend principled alliance with strategic independence – Menzies’ pragmatic nationalism for a new era.

5. Stewardship Over Culture

Menzies articulated a cultural and moral narrative that appealed to identity, aspiration, and belonging. Today’s leaders must again speak to national character: not divisiveness, but unity in democratic values, civic responsibility, and shared ambition.

Conclusion

Robert Menzies reshaped Australia not through revolution but through disciplined, confident, nation-building reform. He nurtured an industrial base, fostered manufacturing capability, supported the car industry as a symbol and engine of modern prosperity, expanded education as a cornerstone of national advancement, addressed social development pragmatically, and strategically repositioned Australia in global trade.

Comparisons with leaders from Curtin to Thatcher, Lee Kuan Yew to Hawke and Keating reveal Menzies as a stabilising reformer – innovative yet moderate, constructive rather than destructive, ambitious for the nation without being ideologically reckless.

The lesson for future Liberal leaders is to emulate his mindset: confidence in nation-building, belief in education, commitment to social cohesion, pragmatic economic stewardship, and a willingness to adapt Australia’s place in the world. A modern Liberal vision inspired by Menzies would seek not merely to govern, but to build – again – an Australia capable, confident and prepared for the future.