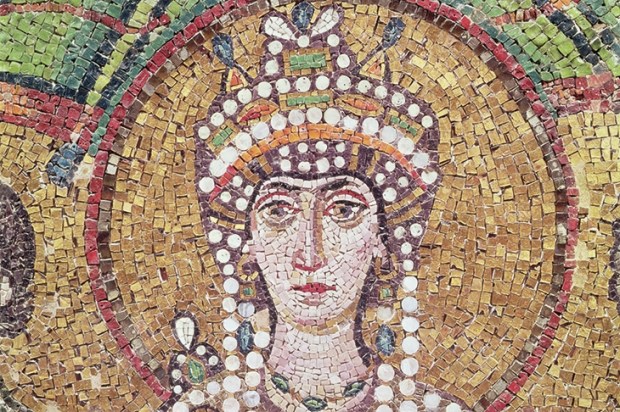

Northern Italians sometimes speak of Sicily as the place where Europe finally ends. The island was conquered in the 9th century by Arab forces from north Africa, who left behind mosques and orchards of pistachio and almond. The Arab influence remains strongest in the Mafia-dominated west of Sicily where the sirocco blows in hot from Tunisia.

Leonardo Sciascia, the Italian detective novelist and essayist, was born in Racalmuto in western Sicily in 1921. The town takes its name from the Arabic rahal maut, ‘dead village’, after Arab settlers found the area devastated by plague. It appears thinly disguised as Regalpetra in Sciascia’s work. For years the Mafia infiltrated the town’s sulphur industry, but the mines are derelict now and the landscape looks denuded. Caroline Moorehead tells us that Sciascia’s father worked in the mines as a bookkeeper and was the son of a caruso, or child miner. Unsurprisingly, sulphur becomes an emblem in Sciascia’s novels for Mafia-related extortion and cruelty. In his bitter-flavoured debut, The Day of the Owl (1961), the face of a bus conductor caught up in a local shotgun vendetta is ‘the colour of sulphur’.

Sciascia (pronounced sha-sha) died in Palermo in 1989. The crucifix in his hands on his deathbed spoke of an 11th hour reconciliation, perhaps, with Catholicism. He was 68. In the decades since then, he has gained long-overdue recognition in the English-speaking world. His great metaphysical thriller Equal Danger (1971), published in Italy as Il contesto, turned detective fiction on its head. A Maigret-like police commissioner pursues a murderer of judges, only to end up a murder victim himself. Sciascia’s reshaping of the detective novel, or giallo (so-called because the first Italian crime fiction came in yellow – giallo – dustjackets) was political. Each investigative step taken by his commissioner leads not to guilt exposed and punished but to injustice upheld and truth perverted. Such is the Mafia reality, according to Sciascia.

In A Sicilian Man, Moorehead offers a fascinating portrait of Sciascia’s life and tumultuous times. The book borrows from the Italian journalist Matteo Collura’s 1996 biography Il maestro di Regalpetra, but Moorehead adds much material of her own. Sicily served Sciascia as a metaphor for the political corruption not only on mainland Italy but also, Moorehead contends, in ‘the world’. I am not sure about that. Certainly in Sicily, with its age-old burden of injustice and death, Sciascia found a sense of drama – an atmosphere of conspiracy – that served him well as a writer who cast an inquisitorial eye on Cosa Nostra malfeasance in all its guises.

Sciascia’s concise, sardonic prose was indebted to that of Voltaire and other French philosophes, Moorehead reminds us, but above all to the Italian Enlightenment figure of Alessandro Manzoni. Sciascia regarded Manzoni’s 1827 historical novel of tyranny in 17th-century Lombardy The Betrothed (I promessi sposi) as a despairing moral treatise on the operation and abuse of power. All his life, Sciascia displayed a deep Manzonian sympathy for what Moorehead calls ‘the losers’ of Sicilian history. He inveighed against Italy’s Christian Democrat party with its larcenous power-brokers, such as Salvatore Lima, who was twice mayor of Palermo until, in 1992, he was murdered (ironically by the Mafia). In his fight against the infâmes of modern Italy Sciascia was, in Moorehead’s view, a moral ‘crusader’ – a word that sits awkwardly with his avowed anti-clericalism and dislike of verbal inflation. Words have to be watched very carefully with Sciascia.

In Sciascia’s work, sulphur becomes an emblem for Mafia-related extortion and cruelty

The Italian fabulist Italo Calvino (who was for many years Sciascia’s editor at the Turin-based publisher Einaudi) was among the first to remark on the ‘impossibility’ of writing conventional crime fiction set in Sicily. On reading the typescript of Sciascia’s second Mafia-themed novel, To Each His Own (1966), Calvino assumed that the sleuth’s piecing together of the evidence was doomed to fail because the Mafia will always ensure its own invulnerability; Sciascia’s was an anti-giallo without a solution. Calvino pronounced To Each His Own superior to The Day of the Owl because, says Moorehead, a little clumsily, it was ‘fuller of irony’.

In smoothly readable if occasionally ungainly prose (‘Disliking pigeonholes, he was irritated when people referred to him as an intellectual’), Moorehead conjures the social stagnation and poverty of postwar Racalmuto, where, in 1948, grimly, Sciascia’s younger brother Giuseppe took his life in the sulphur mine where he toiled as an administrator. His suicide at the age of 25 seems to have unbalanced Sciascia’s father who, already prone to something like persecution mania, shot at (but did not kill) a lawyer who had incurred his displeasure. In spite of these calamities, Sciascia chose to stay on in Sicily. He came of age in fascist-era Racalmuto under the spell of three ‘unusually small’ (small for Sicily?) aunts and for six years in the 1950s was employed there as a primary schoolteacher.

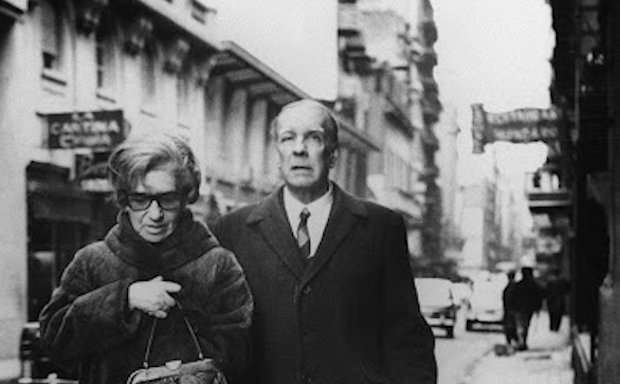

In Moorehead’s description, Sciascia was a ‘small, obstinate man’ of saturnine aspect. That sounds about right. I wore a dark suit for my conversation with him in Palermo in 1985 for the London Magazine, as he himself dressed in what I took to be Sicilian formality. I was 24 and thought I had read everything by Sciascia. I recall that his study was decorated with art nouveau (to Italians, ‘Liberty Style’) objects. He told me that he collected children’s book illustrations by Arthur Rackham. On his desk next to a large sulphur crystal was a silver-framed photograph of the Sicilian playwright Luigi Pirandello, who was born in Girgenti (now Agrigento), not far from Racalmuto. In some ways, says Moorehead, Sciascia had introduced a Pirandellian drama of troubling uncertainties and mirror games to the giallo. He offered me a cigarette from a packet of Benson & Hedges (Sciascia was a heroic smoker) and asked if I would like coffee. This was brought in by his wife Maria (née Andronico), who, I gather from Moorehead, was the daughter of a senior officer in the Sicilian carabinieri. Later that evening a crowd gathered on the pavement outside my hotel where, in Mafia parlance, someone had been rubbed out.

During the early 1980s when gangland violence from heroin trafficking overwhelmed Palermo, Sciascia was expected to make oracular pronouncements on all aspects of Mafia-influenced clientelist crime. But, as Moorehead says, he did not see everything sub specie mafia and knew little about the new metropolitan monstrosity known as the Octopus, which gunned down magistrates and police chiefs with kalashnikovs in broad daylight. In 1987, Sciascia caused a scandal when he attacked the anti-Mafia judge Paolo Borsellino as a careerist with an eye to promotion. He came to regret his attack, but a part of him remained sentimentally bound to the rural Cosa Nostra he had known as a boy in Racalmuto. (‘Fighting the Mafia,’ he wrote, ‘means fighting against myself.’)

A Sicilian Man is not without its (mostly minor) inaccuracies. Pier Paolo Pasolini’s brother Guido was not executed ‘in error’ by anti-fascist partisans in Friuli in 1945; he was very deliberately killed by rival communist partisans in the area. Richard Wagner did not write Parsifal in Palermo; he completed it there. Calvino was not the ‘author of a number of novels’ when he got to know Sciascia in the early 1950s; he had written just two. Candido, Sciascia’s sour-sweet homage to Voltaire, is hardly his ‘most autobiographical book’. That would be Salt in the Wound, from 1956, a chronicle of Regalpetra. But these are hiccups in what remains an excellent introduction to Racalmuto’s most famous literary son and his extraordinary work.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.