The long overlooked staircase by Hogarth at St Bartholomew’s Hospital has been cleaned and restored in a £9.5 million scheme. It is now open to the public, the management says, for the first time since the 1730s, although when I lived nearby in the 2000s, I used to slip in to look at it sometimes. No one seemed to mind. Murals are of course the original site-specific artworks, and you have to enter a working hospital to see this one. Literally: turn right for the clap clinic, turn left for the Hogarth mural.

Turn right for the clap clinic, turn left for the Hogarth mural

You might pass a small group of patients smoking outside in the James Gibbs quadrangle; I remember seeing people who were visibly sick, in wheelchairs or on ventilators, puffing away. Metres from them, you push open a heavy wooden door, and there, in what used to be sepulchral gloom, were Hogarth’s largest paintings.

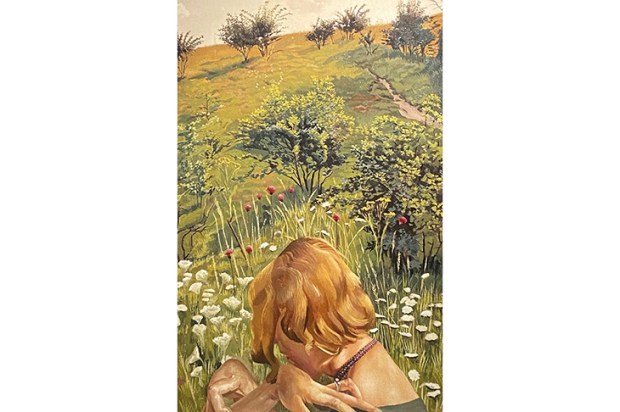

The mural, finished in 1736, is a sumptuous double-decker. You can stand on the upper landing and read it like the spread pages of a book (see below). Before cleaning, it was murky. The ravaged 18th-century faces of the lame, the ‘blind, halt and withered’ loomed out of an indistinct background, uncleaned since 1972. The woman with the ‘green sickness’ (anaemia) was prominent but the rest occluded, the curtains of the grand staircase drawn against further sun damage. The healing ‘Pool of Bethesda’ was a murky trough, barely visible.

The restored Hogarth Stair at St Bartholomew’s Hospital. © MATTHEW ANDREWS

The restored Hogarth Stair at St Bartholomew’s Hospital. © MATTHEW ANDREWS

But now it is revealed as an appealing oasis, beneath optimistic opal skies (Hogarth employed George Lambert, a Covent Garden set-painter, to do them in the manner of Claude). The wooden staircase is buffed and gleaming; and there are brighter bulbs in the original chandelier, a gift from St Barts’s first eye surgeon, John Freke. There is a (banal) audio guide and a video presentation. I could no longer see patients smoking outside – maybe they are vaping elsewhere.

The restoration is illuminating. In the largest tableau, which was painted in Hogarth’s studio then transferred to St Barts (the rest was done in situ), the sick are gathering at the pool of Bethesda (John 5). They arrive on crutches, carried on a bier, or pushing in anyhow, racing to get there because only one can be healed: the first person to step into the waters of the pool after the angel has stirred them.

The angel is just departing; only the little girl with hypothyroidism (‘cretinism’ in the language of the time) seems to be able to see the angel. The waters are moving, its waves lapping, which is what everyone else can see, and it looks as if the rich courtesan, who has already removed her clothes, is going to steal a march on the desperate woman with the sickly-pale baby and immerse first.

But the figure of Jesus is intervening, bringing a bit of order to the situation, by giving a paralysed man the strength to rise up and step into the pool. According to the verse, this man has been lame for 38 years, because others push past him into the waters every time they are stirred. He appears to have camped out, sleeping beside the pool, naked and ready, but always pipped to the post.

As well as appealing to the great British hatred of queue-jumping, Hogarth is playing upon our sense of injustice: what about the others? The chap with the distended belly and the child with scoliosis? When will they be healed? Can we follow Jesus’s example and help get medicine distributed not to those who move fastest, but to those who have been waiting patiently? Perhaps we had better make a donation to St Barts.

St Barts is currently celebrating its 900th anniversary, long ‘ahead of the curve’ in caring for the sick. No surprise then that they were also early adopters of the purpose-built fundraising suite – which is what this staircase effectively is, as it leads to a Great Hall, designed for receptions and events, and adorned with the names of 3,000 donors. Gibbs and Hogarth gave their services for free. The Hall’s Italianate gilded plasterwork ceiling, as well as its windows, have also benefited from the restoration project.

The mural was not acclaimed at the time of its unveiling, perhaps because Hogarth, the bitter caricaturist and creator of ‘The Rake’s Progress’ (1733), was working in a different key here, kinder, warmer, bigger in every sense. Reynolds and Walpole both thought he had over-promoted himself by taking on the elevated genre of history painting. He was certainly aiming to rise to the scale of his father-in-law Sir James Thornhill, who had already completed the Painted Hall at Greenwich and the frescoes of St Paul’s. Hogarth was working to win Thornhill’s blessing, after he and Jane secretly married in 1729, while Thornhill was distracted by the sudden gift of royal permission to copy the Raphael Cartoons at Hampton Court.

I couldn’t see Hogarth’s signature – it’s not really necessary anyway. In the ‘Good Samaritan’ part of the mural, the pug licking its wounds is recognisably Hogarth’s own, and the wounded victim has a trickle of blood on his right temple, just near to where Hogarth’s forehead bore a livid scar. Contemporary gossip suggested that the courtesan in the picture was Nell Robinson, to whom Hogarth had paid his ‘devoirs’.

Addison’s Spectator essays were keen to promote English painting, commending even the soft brown over-painting applied by time. But Hogarth preferred his paintings crisply detailed, and he authorised the mural to be cleaned just a decade after its completion. It is fantastic to see it cherished again, and I commend it to the visitor.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.