London has become the best place in the world to eat out. Of course, there are a thousand other cities with marvellous food, but for organic vitality, ethnic variety and nose-to-tail creativity, London is unmatched. New York and Paris are parochial by comparison.

Two new books locate the source of this revolution of taste and aspiration in the 1980s and 1990s. But, like the Zen paradox, this is both true and untrue. Waves of immigrants immediately raised postwar expectations. It is estimated that 80 per cent of the ‘Indian’ restaurants which dominate high streets are in fact Bangladeshi and that most of the owners arrived from Sylhet immediately after Partition. The Empire struck back.

Before that there were the Italians in the 1950s and 1960s, epitomised by Enzo Apicella who, among many other fine things, designed Pizza Express, which launched in 1964. Six years later, Terence Conran opened the Neal Street Restaurant in Covent Garden, making a symbolic bond between modern design and good food that has not yet been broken (despite the collapse of his restaurant business).

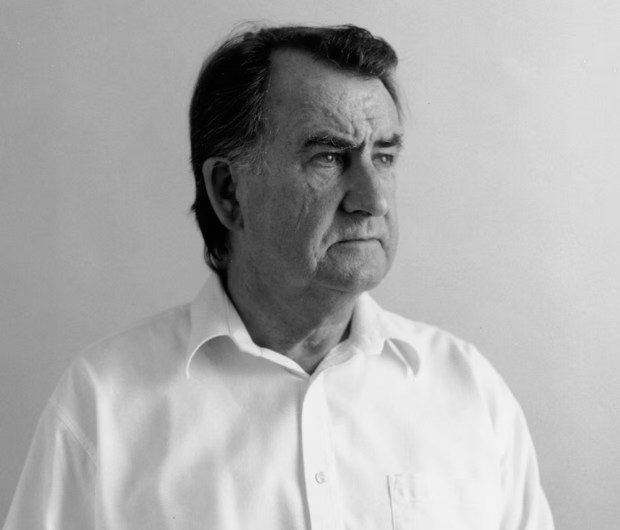

Jeremy King’s name may not be known beyond London, but to sociable metropolitan flâneurs he has the status of a demi-god. (Indeed he once had a popular maitre d’ called Jesus.) No Reservation is a book of charm and sincerity, if occasionally a little repetitive. It is also in a nice tradition of instructive books by hospitality folk, including Marcel Boulestin (the first telly chef) whose Myself, My Two Countries appeared in 1936, John Fothergill’s My Three Inns of 1949 and Danny Meyer’s Setting the Table of 2007 – his Union Square Café in Manhattan setting the gold standard for modern restaurant management.

King is not a chef but an inspired conceptor and proprietor. At the Caprice, Ivy, J. Sheekey and the Wolseley, he raised front-of-house to an art form. His people, as if by magic, but in fact through systematic hard work, know the names of guests who are not even regulars. The magic of recognition makes everyone purr. No Reservation is as much a how-to book for the profession as it is autobiography. With discretion appropriate to his calling, King describes the vile behaviour of many customers and how to deal with it. Interestingly, the worst offenders are men in suits and ties.

There are tantrums, plate-throwing and continuous money worries. But all is calm on the surface. Neither servile nor superior, but 6ft5in of immaculate Timothy Everest threads, King restlessly patrols his restaurants, bending over every customer as if they were the most important person in the room. On the restaurant floor and in this book he serves wisdom. He says he is egalitarian, but perhaps only in the sense that regulars such as David Beckham and Harold Pinter were treated identically. His democratic instincts did not prevent his restaurants becoming celebrity petting zoos, although King was the man who stopped Andy Warhol photographing the famous at the Caprice.

His mastery of difficult people is a thing of wonder. Waiting for a late-running guest, I once asked him: ‘Exactly which is the best table?’ Not missing a beat, he smiled thinly and replied: ‘The one you are sitting at, Stephen.’ He has said that many times before and it always works. The food in his restaurants, while never bad, has never been the point. Instead, he creates a fantasy world in which we can all perform.

After King’s orotund, elegant sentences and his serene presence, Andrew Turvil’s Blood, Sweat and Asparagus Spears feels like meeting a frantic restaurant enthusiast in a pub. Indeed, this former editor of The Good Food Guide confesses to having owned one. The book reads like a trawl through the GFG archives: 33 long-established restaurants and their stand-out dishes are the origin of each discursive chapter. There is an ironic Berni Inn, but you will also find those darlings of the age: black cod Nobu, Conran’s Pont de la Tour and Rick Stein’s Padstow. Each starts a breathless conversation.

There is an irrepressible matiness about Turvil which some will find easygoing, others hard work. His need to connect with the 1990s is real, but he seems a latecomer to the party. That was the decade when Nigella drizzled oil on these very pages. And it was the era of Heston’s triple-cooked chips (triple being a first in this context), Marco Pierre White returning his Michelin stars and the onward march of bruschetta. What a distant age that seems.

In Turvil’s chatty style frays are entered into and many things are ‘decidedly’. While aiming for the same target, his book lacks the synoptic genius of Brillat-Savarin, who said in La Physiologie du Gout of 1826: ‘Tell me what you eat and I will tell you what you are’? Turvil (and King) rather say: ‘Tell me where you eat and I will tell you what you want to be.’

A significant influence on London dining in the 1990s was Joe Allen. After he prised himself away from the bar of P.J. Clarke’s, he set up his eponymous restaurant in New York’s theatre district. A London branch opened in 1977 and, under the management of Richard Polo, incubated King and the late Russell Norman, whose restaurant Polpo created the still current vogue for small plates. Allen knew a thing or two about customers who make a fuss about their table (like Jeffrey Archer). King enjoys his marvellous mantra: ‘Those who count don’t care, those who care don’t count – which is also both true and untrue.

These very readable books show that restaurants are about much more than eating. But The Great Book of Modern Restaurants? Yet to be written.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.