Our remarkably high living standards from the 1840s onwards came from ordinary people struggling for property rights. They won them, and without this Australia would have achieved nothing.

Our land laws fostered our economic development, unlike Argentina’s, for example, where economic performance fell behind that of Australia. As Ian McLean writes, now nearly all ‘first world’ nations are democracies.

Our 1850s ‘one-man one-vote’ constitutions were a struggle between the two visions of property. The squatters were large landowners who ran vast sheep and cattle herds on land they wanted to keep. On the other side were the ordinary people, who also wanted land. Both won.

As soon as rudimentary ‘one-man one-vote’ democracies were achieved in the three largest Australian colonies, ordinary people forced land reform through reluctant Upper Houses which were partly controlled by the squatters.

Leaders such as William Wentworth in NSW, John Foster in Victoria, and John Baker in South Australia fought with some success to achieve less democratic Upper Houses.

As soon as democracy was achieved in South Australia, ordinary people forced the landmark Real Property Act 1857 through Parliament which provided a statutory register of property and strong protection for landowners.

As the first Premier of South Australia under self-government, Boyle Travers Finniss, said the Real Property Act 1857 (Torrens Title) was ‘strictly forced upon the Governor and Parliament by the will of the people … few members dared to vote against any of its provisions’.

Land reform in the 1860s was similarly forced through by the people. It was the result of ‘a popular campaign of four years and by political pressure’ rather than ‘the deliberate wisdom of the Parliament’ in NSW as Stephen H Roberts wrote.

Squatters resisted land reform as best they could, but as Roberts said, maps showed they were often pushed to the fringes of each colony.

The Torrens Title was, together with Alfred Deakin’s wages boards of 1896, possibly the most influential Australian colonial Act worldwide apart from democracy and the secret ballot.

William Wentworth, the leading politician developing NSW’s first constitution providing for self-government, said in 1853 that a democracy would be a mobocracy:

‘What security for person or the rights of property, or the administration of the law, or social order, would there be under such a constitution?’

Thomas Babington Macaulay, the great historian and Whig politician, said in 1842 that democracy would result in ‘general anarchy and plunder’.

None of these warnings came true. Land reform stabilised the nation by giving ordinary people a stake in the economy. They became conservative landowners.

Property rights came under later challenge. The Australian Labor Party formed to represent workers after their defeat in the 1890s ‘great strikes’. The new party became ‘socialist’ in its objectives.

In 1947 the then Chifley Labor government forced the Banking Act 1947 through Parliament. The Act enabled the Australian government to compulsorily acquire private banks and so nationalise a key part of the market economy.

The private banks challenged the law. In the 1948 Bank Nationalisation Case, the High Court held the Act to be an unconstitutional interference with inter-state trade and commerce and would violate constitutional guarantees of no acquisition of property without just terms.

As my friend Alan Moran points out, states are not subject to the ‘just terms’ requirement and are now used by the Commonwealth to override farm property rights in pursuit of our vast energy experiment, without just terms.

This can be devastating for local farmers.

Another challenge to property rights came from the 1992 High Court Mabo decision, which rejected the more conventional Common Law approach that acquisition of title by the Crown extinguished all prior title, including ‘Native Title’, unless expressly authorised by the Crown.

One of the majority judges explained ‘native title’ at one conference I attended as akin to an easement, a simple right of way on a property which is very limited in nature. But this does not, for example, account for the alleged ‘spiritual’ aspects of land which have become an important campaigning tool.

The Keating Cabinet considered the legal guidance given by the Court ‘thin’. Practical problems erupted and some are still continuing over 30 years later, concerning pastoral leases, mining approvals which are foundational to our standard of living, land clearing, and even access to recreational rock climbing.

An estimated 40-49 per cent of the Australian landmass is under Native Title in some form. Further discord seems likely.

In the postwar period, Australia became a nation of property owners, peaking in 1966 with 70-73 per cent of citizens owning their own home, with a relaxed lifestyle to accompany their property. They might also own a pool, and a large Australian-made car, or even two. In 1901, home ownership was about 40 per cent.

Australians lived fortunate lives, comparatively, and did since the earliest times. Even convicts were found in the 1826-1829 Bigge Reports to be living comparatively well, sometimes described as if being on a holiday rather than penalised as criminals.

Australian governments, however, failed to preserve this essential compact of property owning with the Australian people with the level in 2025 dropping to 66-67 per cent. Some young people are locked out of the property market now, unless they have access to the bank of mum and dad.

Property rights were the basis of the Australian settlement, which is one of the most successful in history on any measure of human rights, prosperity, and democracy. We should support rather than consistently undermine them.

Our governments must act to make more land available for housing and remove barriers to new building. We must remain the country for ordinary people.

We have a consistent problem in having sensible debates about what is in our national interest. What exactly is the benefit to Australia from high immigration levels for example? Can government tell us?

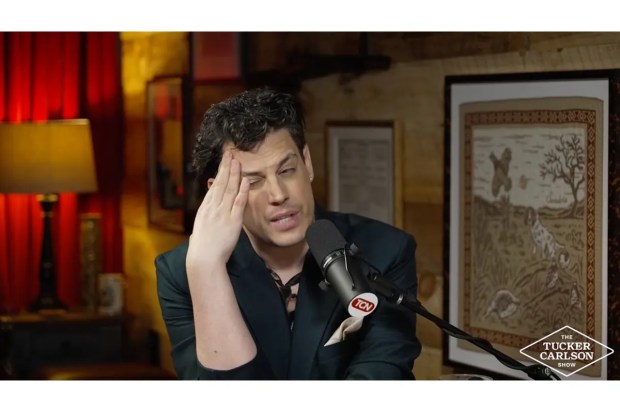

The Hon. Reg Hamilton, Adjunct Professor, School of Business and Law, Central Queensland University