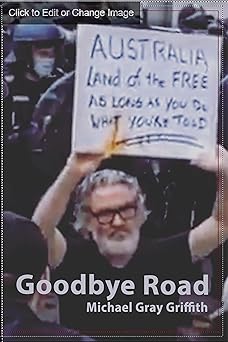

I don’t want to forget, but it hurts when I remember. Yet here we are … we’re on Goodbye Road, as Michael Gray Griffith calls it, in a collection of essays of the same name, edited by John Stapleton.

The essays document the deeply personal and tragic stories of the outcasts of the Covid era, told to him directly during his travels around the country.

These include interviews with people the media never find, articulating the hardships of the consequences of the government responses to the hysteria of the day. Consequences which will never find their way back to anything resembling sorrow, remorse, contrition or apology from the perpetrators of these monstrous injustices.

Goodbye Road, available on Amazon

Those who led the injustices won’t read these stories. They are not for them anyway. They’re for the outcasts and hitchhikers on Goodbye Road. The ones who trudged alone, convinced no one else would ever come down this road. The ones who gratefully accepted a lift from a fellow leper, from a friend, or a sister who understood. One by one, new connections were forged along Goodbye Road. Goodbye Road is still lonely, but less lonely than it was. We’re out here, sometimes resting, but soon enough pushing along again, with our thumbs out each time we hear a car. Perhaps they’ll stop?

Read the stories that Michael Gray Griffith re-tells. The stories we never heard while submerged under torrents of safe and effective advertising. Be thankful that nothing like that happened to you, or if it did, take comfort in knowing others understand deeply.

The early protests in Melbourne are described firsthand, a narrative that was twisted when portrayed on the nightly news. The author was arrested and injured by a rubber bullet at the Shrine of Remembrance.

We learn of the author’s journey from confusion to bemusement at the weird developments like elbow handshakes and the sudden appearance of hand sanitizer everywhere. Surreal moments caught the irrepressible spark of light that is humanity, pushing back against the darkness of the day – a dancer under a streetlamp providing an invisible audience a glimmer of hope.

The stories are about freedom, fundamentally. What does it mean, how do we keep it, and what are we prepared to do to defend it?

What are we to make of a grandmother shoved to the ground and pepper-sprayed to her face? Or a man from Perth trying, but failing, to get to Brisbane to visit his elderly parents, Hungarian migrants?

People who lost their job, detectives encouraged to retire, the convoy to Canberra, reflections on hope, and suspended doctors. Dead and paralysed sons unable to be transported home because of border closures, transplant candidates denied until vaxed. Take your pick, the stories are vivid.

Among the stories are essays of hope and vision for what Australia was, might have been, and might yet be. Reflections on manliness and men, on Australian-ness, on courage.

These essays are an important artefact in the history of the Covid era.

As we have seen, official enquiries avoided the curliest questions and delivered gaslit recommendations about how we should have locked down sooner and harder, or distributed unproven therapeutics more quickly. We can only hope that someone, somewhere, one day in the future, will unearth these ‘dead C stories’ and gain a fuller perspective on the era and a more graphic illustration of the real impact on ordinary people.

Perhaps one or two of the stories will stick in your mind.

Many would like to forget what happened during Covid, but it did happen, and these stories are the proof. Personal, simple, and heartbreaking. And so we must remember, we must tell the stories, and if that means we have to suffer painful memories, then so be it.