As the liberal international order fades, institutions that were created as part of the euphoria of liberal internationalism are becoming unmoored from foundational values. As relative power is ceded to newly powerful but illiberal countries, Western powers that designed, created and provided stewardship of the post-1945 order are losing their controlling grip of the institutions of that order.

The ICC covers four crimes (Articles 5–9): genocide, crimes against humanity, war crimes and, since 2018, aggression. The first three include murder, extermination, killing or causing serious bodily or mental harm to members of a group, or their torture, rape, sexual enslavement, any other form of sexual violence, taking of hostages and intentionally attacking civilian targets. The definition of genocide includes the ‘intent to destroy, in whole or in part’, a national, ethnic, racial or religious group. The fourth crime includes ‘the planning, preparation, initiation or execution… of an act of aggression’. A series of attacks before, on and since 7 October, along with serially repeated threats from responsible leaders, show Hamas has committed all the above crimes, including the necessary element of intent. Simply put, if Hamas could, it would destroy the state of Israel and exterminate and ethnically cleanse Jews from the Jordan river to the Mediterranean sea. But it cannot. Israel could, but chooses not to.

The noble vision behind the creation of the ICC was to hold perpetrators of mass atrocities inside sovereign jurisdictions, including terrorist groups and militias, to international account if their host country’s own processes were not up to the task. This doesn’t mean that all advocates were entirely happy with the ICC clauses and performance. From the start, I was unhappy with the politicisation of the ICC with cross-linkages to the UN Security Council. Permitting Council members who refused to join the ICC, including China, Russia and the US as permanent members, to vote on referring and deferring ICC investigations violated principles of natural justice.

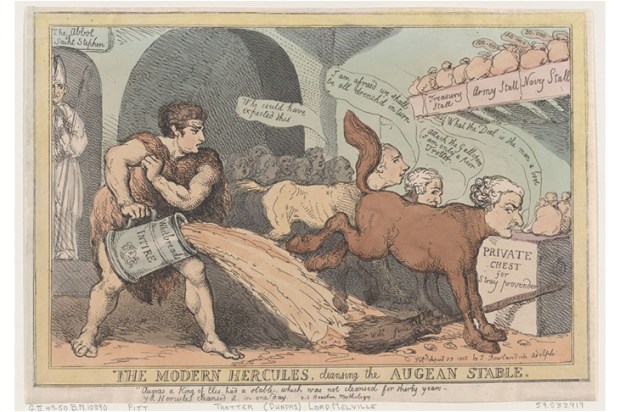

Every society, including international society, has some members whose intellectual conceit and moral arrogance impels them to want to substitute their judgment for the outcome of democratic processes. In an article for the Japan Times as far back as 2005, I warned of the instinct to ‘judicial romanticism’, the pursuit of judicial solutions to problems that are essentially political. We see this domestically in the misuse of lawfare by environmental activists and in the weaponisation of justice against Trump in the US and against Modi’s opponents in India. In international politics, a commitment to justice at any price leads the romanticists to discount diplomatic alternatives. In an article in the Hindu in 2008, I warned of this risk in the pursuit of Sudan’s President al-Bashir by the ICC against the wishes of the African Union worried about the negative impact on the search for peace through negotiations.

The Rome Statute expects the prosecutor to be a person of ‘high moral character’ (Article 42.3). There was some plausible information that in 2005, the first ICC prosecutor subjected a South African journalist to sexual coercion or rape. The ICC official who had arranged the interview recorded a phone conversation with the weeping and distressed journalist. In 2006 Christian Palme, an ICC official, filed a formal internal complaint; the prosecutor denied the charge; a panel of judges dismissed the complaint and ordered the destruction of the tape; the prosecutor fired Palme, who appealed to the International Labour Organisation and was fully exonerated by it on 9 July 2008 with a ruling that (1) the journalist had ‘indicated unambiguously that the prosecutor “took [her car and house] keys” and she had consented to sexual intercourse “to get out of [the situation]”’; and (2) the evidence of the ICC official to whom she had spoken on the phone was ‘secondary evidence but, depending on the circumstances, it may have been probative in criminal proceedings’. The ILO also found the prosecutor guilty of a ‘breach of process’ in firing Palme and ordered a payment of €248,000 compensation. One day after the ILO findings, the prosecutor told the Washington Post of his intention to seek the arrest of President al-Bashir. That became the big international story. The sordid saga, and much else besides, is told by the respected Africa experts Julie Flint and Alex de Waal in an article in World Affairs Journal (Spring 2009, https://www.jstor.org/stable/20671408).

The main charge against Israel is a disproportionate civilian toll. In the second world war, civilian dead outnumbered soldiers killed by two to three times. They comprised between two-thirds to three-fourths of the dead in the 1950-53 Korean, 1990-91 Persian Gulf and 2003-19 Iraq wars. In Gaza, because of Hamas’s policy of hiding fighters and leaders amidst civilians, it’s hard to separate fighters from civilians in the fatality count. Israel’s estimates put the numbers killed in Gaza by mid-May at 14,000 militants and 16,000 civilians. Barry Posen of MIT, in a long and nuanced essay in Foreign Policy, writes that ‘given its own military history’ in Afghanistan, Iraq, against Islamic State etc, the US ‘does not have much ethical ground to stand on in decrying Israeli strategy’; when the US ‘is provoked, it is historically quite ferocious’. Nor do US allies like Australia and the UK and Arab and Islamic governments (Libya, Sudan, Yemen, Syria). For its part, Hamas is ‘unconcerned about putting Palestinian civilians in harm’s way. Indeed, this is a feature, not a bug, of their political and military strategy’. So much so that ‘human ammunition’ better describes their strategy than ‘human shield’. John Spencer, chair of urban warfare at West Point military academy, tweets that ‘Israel has done more to prevent civilian casualties in war than any military in history’, setting a hard-to-repeat standard for others.

The principle of complementarity stipulates that the ICC can exercise jurisdiction only if the state is genuinely unable or unwilling to investigate and prosecute alleged war criminals (Article 17). Aharon Barak, Israel’s ad hoc judge on the ICJ, points out that Israel’s Supreme Court has held that torture is prohibited, religious sites and clergy must be protected and all captives must be afforded fundamental guarantees. These edicts set the standards for the conduct of the Israeli military. International law is an integral part of the military code and ‘Israel’s multiple layers of institutional safeguards also include legal advice provided in real time, during hostilities’.

Israel’s judiciary is so powerful and robustly independent that Netanyahu was in deep domestic trouble for having picked a fight with it before Hamas created this crisis by its unprovoked and depraved attack, in which it raped and maimed women, and took children, women and elderly hostages before scuttling back to their tunnels and putting Palestinian civilians in harm’s way of the inevitable fierce Israeli retaliation after the initial shock and horror. Sir Michael Ellis, a former UK attorney-general, believes the ICC move against Israel’s leaders ‘violates the court’s charter and integrity’. With the decision by the ICC prosecutor to seek arrest warrants for Israel’s PM and Defence Minister, we might be seeing the final nail in its coffin. Israelis seem determined not to risk a never-ending series of future pogroms and are united across the political spectrum in the grim resolve to continue the military campaign until Hamas is comprehensively defeated. Why wouldn’t they be?

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.