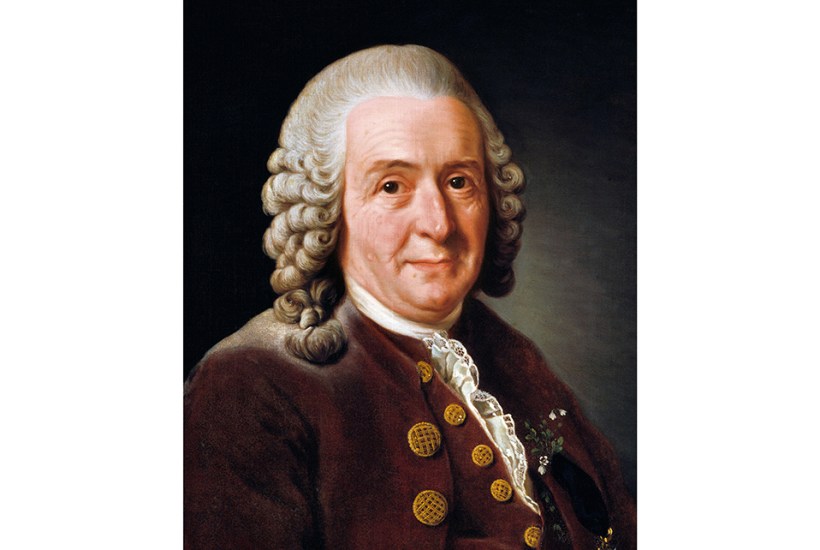

Carl Linnaeus and Georges-Louis Leclerc, Comte de Buffon were both taxonomists, born in the same year (1707), but apart from that they had little in common and never met. Buffon was French, Linnaeus Swedish. Buffon was suave, elegant, tall and handsome (Voltaire said he had ‘the body of an athlete and the soul of a sage’), whereas Linnaeus was a bumptious little man (under 5ft), who was widely regarded as uncouth.

Already a subscriber? Log in

Subscribe for just $2 a week

Try a month of The Spectator Australia absolutely free and without commitment. Not only that but – if you choose to continue – you’ll pay just $2 a week for your first year.

- Unlimited access to spectator.com.au and app

- The weekly edition on the Spectator Australia app

- Spectator podcasts and newsletters

- Full access to spectator.co.uk

Or

Unlock this article

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in